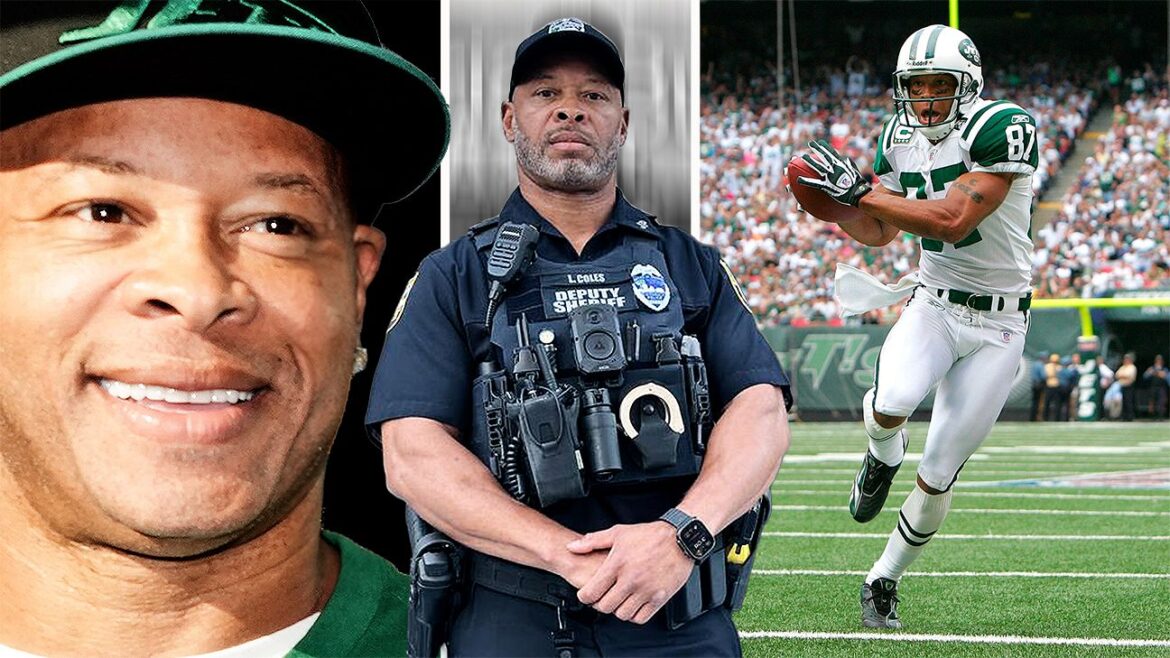

JACKSONVILLE, Fla. — Officer Laveranues Coles was standing outside Target one day recently, scanning the parking lot for a perpetrator who had fled after causing a disturbance inside. Coles was approached by an elderly woman, a shopper walking to her car.

She had no idea he was one of the NFL’s most productive wide receivers from 2000 to 2009. All she saw was a police officer with a handgun, a taser and a tactical vest that included a body cam, pepper spray, handcuffs and police radio. In her eyes, he was true blue.

“I feel safe with you here,” she told Coles, impacting him in a way she never could’ve imagined.

If she only knew what he had endured in life, how he was sexually abused as a child by his gun-wielding stepfather, how he was arrested twice and thrown off the Florida State football team in the middle of the 1999 season and how he was branded by the media as the “bad boy” of the 2000 NFL draft.

If she only knew how this middle-aged former star athlete, with two metal hips, punished himself for months in the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office Academy, how his body seized up at night because of the physical strain and how he almost gave it all up to go back to his pre-police life, which was good and comfortable.

If she only knew.

But she still made his day — really, his year — with her compliment.

“Meant the world to me,” said Coles, calling it the most fulfilling moment of this entire mid-life journey.

One that is causing angst among family and friends.

COLES IS HEARING a simple word a lot these days: Why?

He’s certainly not doing it for the money. Over 10 NFL seasons, including seven with the New York Jets, he made $42 million. He described himself as a good saver and a sound investor, and there’s no doubt in his mind that he could live off his nest egg for the rest of his life.

So, no, the $68,472 salary he’s drawing as a member of the academy’s field training program isn’t the reason he decided to become a police officer last January. Even as a full-fledged officer — his probationary period ends Jan. 23 — his salary will be $70,032 once he reaches one year of service.

Again, this isn’t a money thing.

Coles joined the police to add purpose to his life, to help his community and to help those who remind him of his younger self. Paraphrasing the lyric from Coldplay’s “Viva La Vida,” he patrols the streets he used to own. He grew up in Jacksonville and became a local legend at Ribault High School, where he rushed for nearly 5,000 yards as a running back before lining up at wide receiver for the late Bobby Bowden at Florida State.

“I want people to understand that no matter what stage you’re in, or where you’re at in life, it’s never too late to get up and do something,” Coles said in a quiet moment at the Police Memorial Building, a drab, boxy complex in downtown, only a few blocks from the Jacksonville Jaguarsje’ home at EverBank Stadium.

After retiring as a player following the 2009 season, Coles considered a career in football. He interned in the Jets’ front office, but he didn’t care for the business side of the game.

He went home to Jacksonville, obtained a liquor license and invested in popular bars, along with a skin-care product store in an upscale area. He also dabbled in the stock market and played a lot of video games with his kids, enjoying a cushy lifestyle. He stayed close to his community, buying equipment for his old high school and funding tutorial programs for college-entrance exams. Eventually, he earned an online degree in criminology from California Coast University, which sparked his interest in law enforcement. Friends in the sheriff’s department encouraged him to join the academy, and so he did.

At 47 years old, he started a new career — a polarizing move that goes beyond his age, he soon learned. He was taken aback by the sharp, divergent opinions of his decision. The fallout, he said, has been “stressful.”

Some close to him applauded his civic-mindedness. Others, including friend Tyler Perry, the actor and filmmaker, questioned his judgment. As Coles said, “It’s not a good look to some people,” alluding to those with a negative perception of the police. They worry about his safety.

“It’s not something that America loves, like football,” Coles said. “People’s opinions, especially the people that are closest to me, really matter. I’m just trying to get them to understand that it’s not as bad as they would think. But I get where they’re coming from.”

Former Jets teammate Wayne Chrebet, one of his closest friends, gave his full support.

“I told him this is a major, major accomplishment,” Chrebet said. “After everything he’s done in his life, to do this in his late 40s, I was like, ‘This is incredible.'”

Retired coach Dan Henning, Coles’ first offensive coordinator with the Jets and instrumental in the team’s controversial decision to draft him, echoed Chrebet.

“I can’t tell you how proud I am of Laveranues,” Henning said. “I think it’s wonderful.”

COLES HAS BEEN on both sides of the law.

In 1998, he was charged with simple battery stemming from an altercation with his former stepmother, who had earlier fought with Coles’ mother. He pleaded Nolo Contendre (no contest) to misdemeanor battery and received one year probation, 150 hours of community service and was suspended for a game by Florida State.

His life was dramatically altered in October 1999, when he was arrested with teammate Peter Warrick for felony theft in Tallahassee, Florida. They received a discount on clothing at a Dillard’s department store, where Warrick knew the cashier. Coles received $247 worth of clothes for $20.

The charges were reduced to a misdemeanor. Coles was sentenced to 10 days in the county work program, which meant cleaning up garbage along a highway. He was removed from the Florida State team.

Talent evaluators considered him a potential first-round pick based on pure talent, but his stock dropped because, in his words, he was perceived as a “thug” without a school. He was mad at the world. He felt alone, trapped in a dark place. This, he said, was the absolute low point.

Hindsight has provided a different perspective.

“Really, being honest,” said Coles, relaxing at the police station after an 11-hour shift earlier this month, “it was the best thing that happened to me.”

By his own admission, he was a spoiled athlete immersed in the entitlements of big-time college sports. Looking back, he believes he needed to get knocked off his pedestal. It cost him a lot of money. He fell to the third round, where the Jets — looking to replace star receiver Keyshawn Johnson — stopped his free fall.

There was a heated back and forth in the draft room between Bill Parcells, their top football executive, and director of security Steve Yarnell. Parcells had dispatched Yarnell, a former special agent for the FBI, to investigate Coles’ background in Florida.

Yarnell vouched for the player, holding his ground when Parcells challenged him in front of the room. Yarnell was told that he’d be out of a job if they drafted Coles and he screwed up.

“That sounds like something I’d say,” Parcells recalled. Eyewitnesses were stunned by the intensity of the exchange.

“Coles tries to portray himself as a victim in most of the incidents in which his actions have caused him to get into trouble,” Yarnell wrote in his 2000 report, obtained by ESPN. “He does have a likable side and seems to realize that he is on the edge of the cliff. I strongly believe he can be worked with; however, he cannot be left to his own devices for quite some time.”

Henning, too, was involved in the vetting process. He flew to Jacksonville to meet with Coles at an Olive Garden. He found him to be humble, forthright and smart. Henning’s wife met Coles outside the restaurant when she arrived to pick up her husband.

“She was enthralled with him, too,” said Henning, who lobbied team officials to draft Coles.

What the Jets didn’t know — what very few people knew — was that Coles had been sexually abused as a middle schooler, from the ages of 10 to 13. His mother, Sirretta Williams, worked nights. When she was gone, her husband — Laveranues’ stepfather — molested him, threatening to kill him and his mother if he told anyone.

Coles lived with the shame and fear, finally revealing the secret to a persistent police officer who was investigating a schoolyard brawl in which Coles beat up a classmate. His mother divorced the man, who wound up serving 3 ½ years in prison.

He carried it all with him to the NFL, often appearing moody and sullen. He arrived at the Jets with a “tough outer layer,” according to Chrebet, who still believes his friend “has a problem trusting people.” Coles doesn’t deny that.

“My fiancée, she thinks I’m still traumatized by that to this day, based on how I carry myself,” said Coles, who went public with his story in 2005 and received universal praise for sharing his unimaginable horror.

Looking back, he credits that police officer with helping him through the crisis, calming him with assurances that he would be safe and protected. It’s one of the reasons why he developed an affinity for the police.

“Now,” Coles said, smiling, “I’m actually the one pulling up to the scene trying to make things better.”

EARLY IN THE training academy, which lasted nine months, Coles was tased and pepper-sprayed — mandatory for trainees. He did a quarter-mile crab walk in 90-degree heat, with searing asphalt that made his hands feel like they were on fire. There was an obstacle course, a one-mile run and too many pushups and pullups to count.

All told, he logged 770 hours of basic law-enforcement training, as mandated by the state, plus another 500 hours to satisfy the requirement of the Jacksonville Sheriff’s Office. Officer Jimmie Collins, a 24-year veteran, said they lose a lot of trainees because they can’t handle the physical and mental challenges.

“They didn’t tell me how hard this was going to be,” said Coles, who was so fast coming out of college that scouts had timed him under 4.3 seconds in the 40-yard dash — speed that helped him to more than 8,600 receiving yards with the Jets, Washington and Cincinnati Bengals.

At the academy, every day was a different physical challenge, not easy even for an NFL vet who endured 153 games, seven documented concussions and four hip surgeries — including two replacements. At night, his body cramped, sometimes violently. He thought about resigning, but he remembered what his son, Landon, a Harvard Law student, had said about him:

Dad never quits anything.

“It gives me a sense of purpose,” the father of four said. “Just like with the NFL, they kick off on Sunday, regardless. They don’t care who’s there and who ain’t there. Same thing with this job. Whether I’m here or I’m not here, police are patrolling the streets.”

So he pushed through the pain, studied hard, graduated from the academy and received a field assignment. The city of Jacksonville is divided into six police districts. Right now, he’s patrolling district five — the Riverside neighborhood — which has the second-highest crime rate, according to recent police statistics.

“He’s the right person for this job, for everybody in the city of Jacksonville and for the citizens,” said Collins, one of Coles’ childhood friends. “It will be a tremendous honor having him work side-by-side with me because these are the type of people we want for the citizens and the community. He’s not a quitter, and he loves challenges.”

Coles has been called to car crashes, domestic disputes, thefts and a suicide. One time, a guy wanted to fight him in the street. Coles was able to de-escalate the situation with a calming voice. He has a gentle side, an ability to connect with people in distress, maybe because he used to be one of them.

Occasionally, he gets recognized. One time, he was knocking on doors, canvassing a neighborhood for information. A guy who answered a door yelled into his house, “You won’t believe who’s here.” Yes, there was a selfie taken.

Out on the streets, Coles learned quickly that if someone calls the police, they aren’t having a good day. He has walked into “high adrenaline” situations, as he called them, but nothing that felt life-threatening.

When he encounters kids, he tries to share his experiences. He knows rock bottom. He knows what it’s like to feel alone in the world. He knows what it’s like to be arrested.

“Anything about his past, to be on the other side of that, it’s kind of like a full-circle thing,” Chrebet said.

There are times when human emotion conflicts with the police handbook. Coles encountered an elderly man caught stealing groceries. The man said he had no income because of the federal government shutdown, and that he needed to feed his family. He had no criminal history.

Coles saw remorse in his eyes and wanted to let it slide, paying for the groceries out of his own pocket, but there was no room for discretion. A probationary officer, he played it by the book. So he gave the man an NTA (Notice to Appear), basically a summons.

“My heart felt for him,” Coles said. “I know he made a bad decision, but a bad decision shouldn’t define your life.”

Officer Coles has proven that.