Greetings, fellow time travelers. Let’s take a brief respite from the onslaught of new product introductions and check in on everyone’s favorite feature here on MyGolfSpy: History’s Mysteries.

It is your favorite, right?

In History’s Mysteries, we love diving into the events of the past and connecting the dots of time. As the saying goes, those who don’t learn from the past are doomed to repeat it.

Speaking of doom …

Over the years in this space, we’ve examined the twists and turns of bygone OEMs and this edition of History’s Mysteries is especially timely. Today marks the 31st anniversary of a natural disaster that directly led to the downfall of a legendary golf ball manufacturer.

This is the story of Japan’s Great Hanshin Earthquake and how it doomed the original Maxfli.

History’s Mysteries: Maxfli and the morning of Jan. 17, 1995

It’s 5:46 a.m. in the city of Kobe, one of Japan’s leading industrial centers and shipping ports. It’s also the home of the Dunlop Kobe Factory, the crown jewel of Dunlop’s global manufacturing complex and the home of its flagship golf ball, the Maxfli HT Balata.

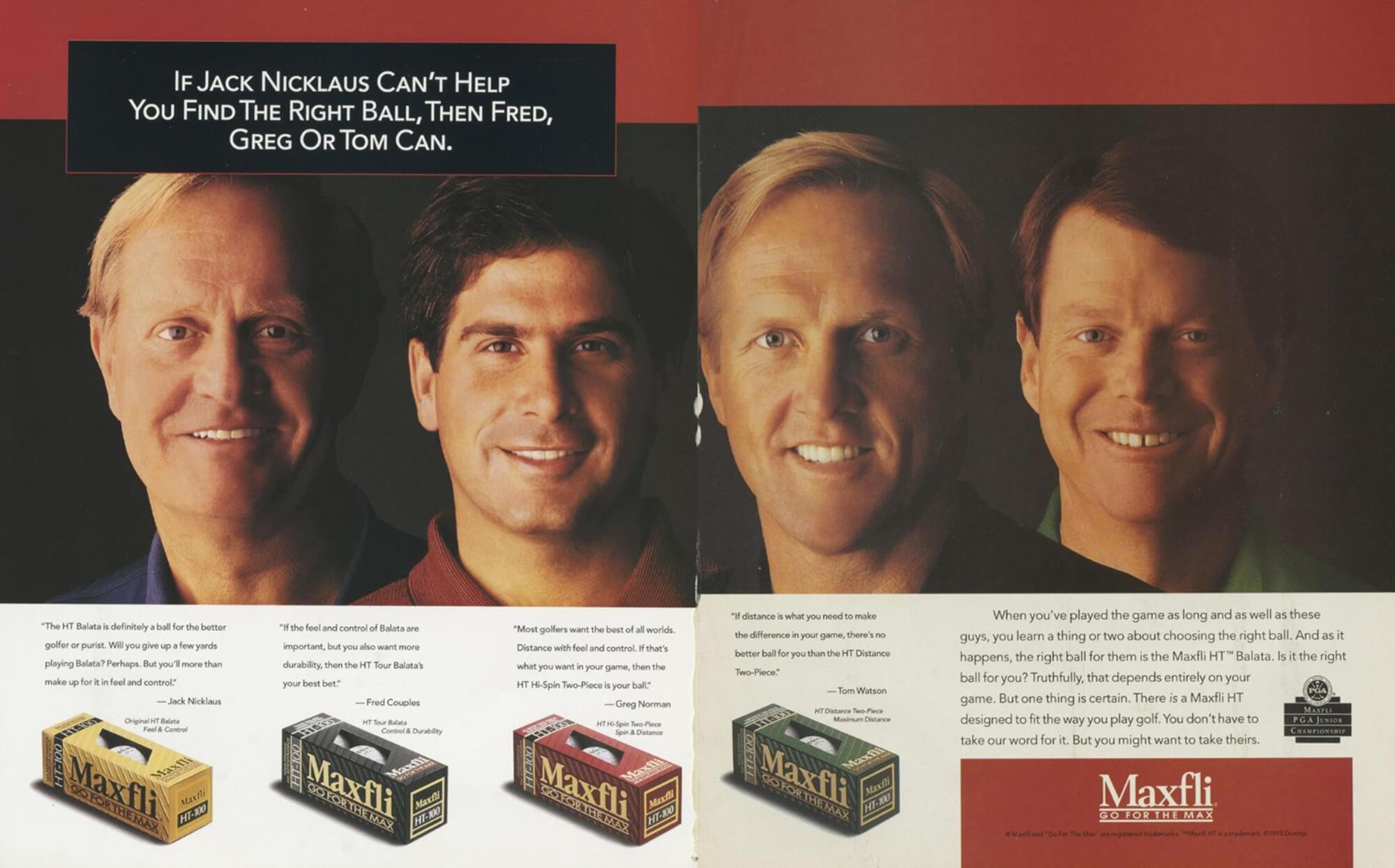

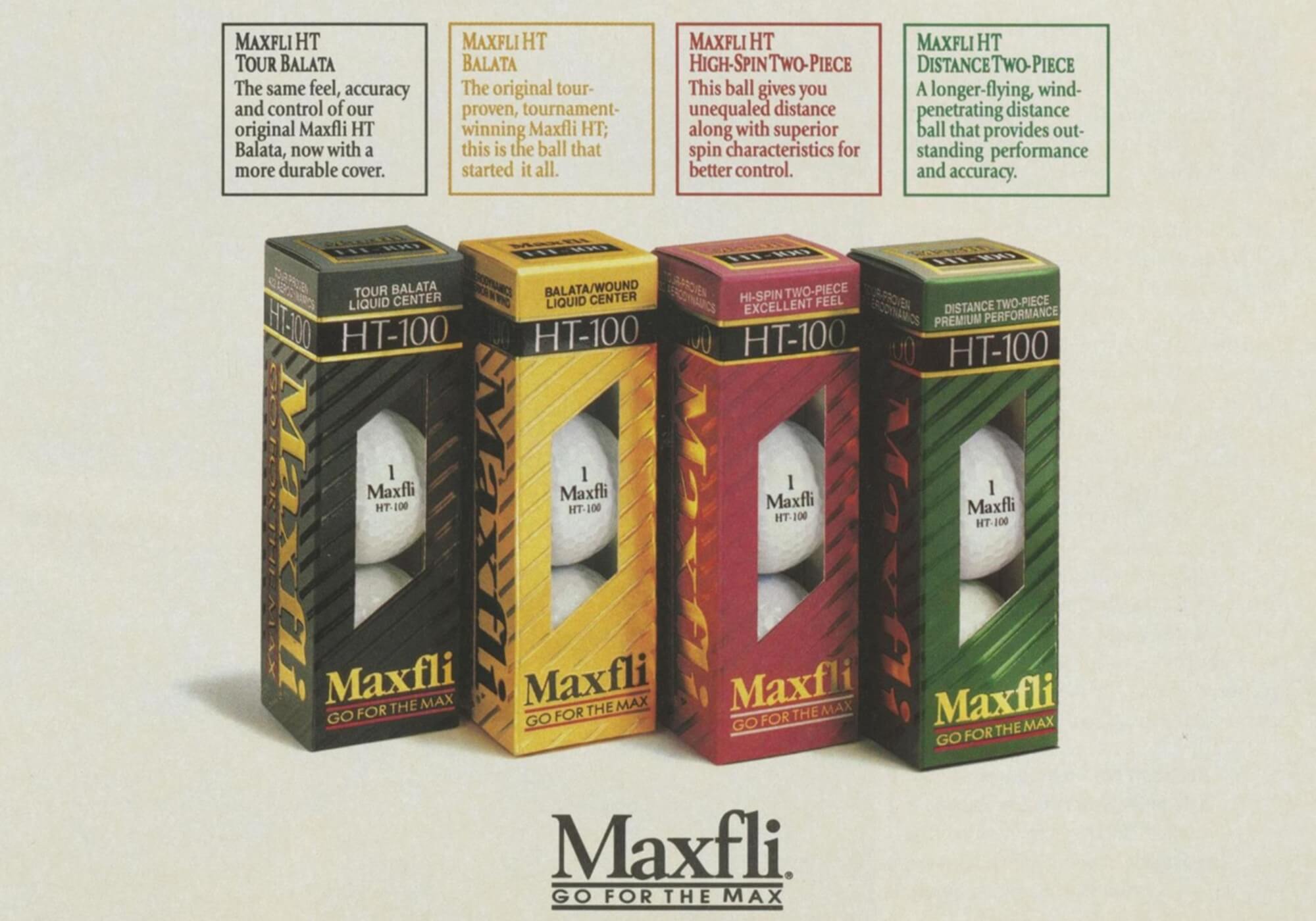

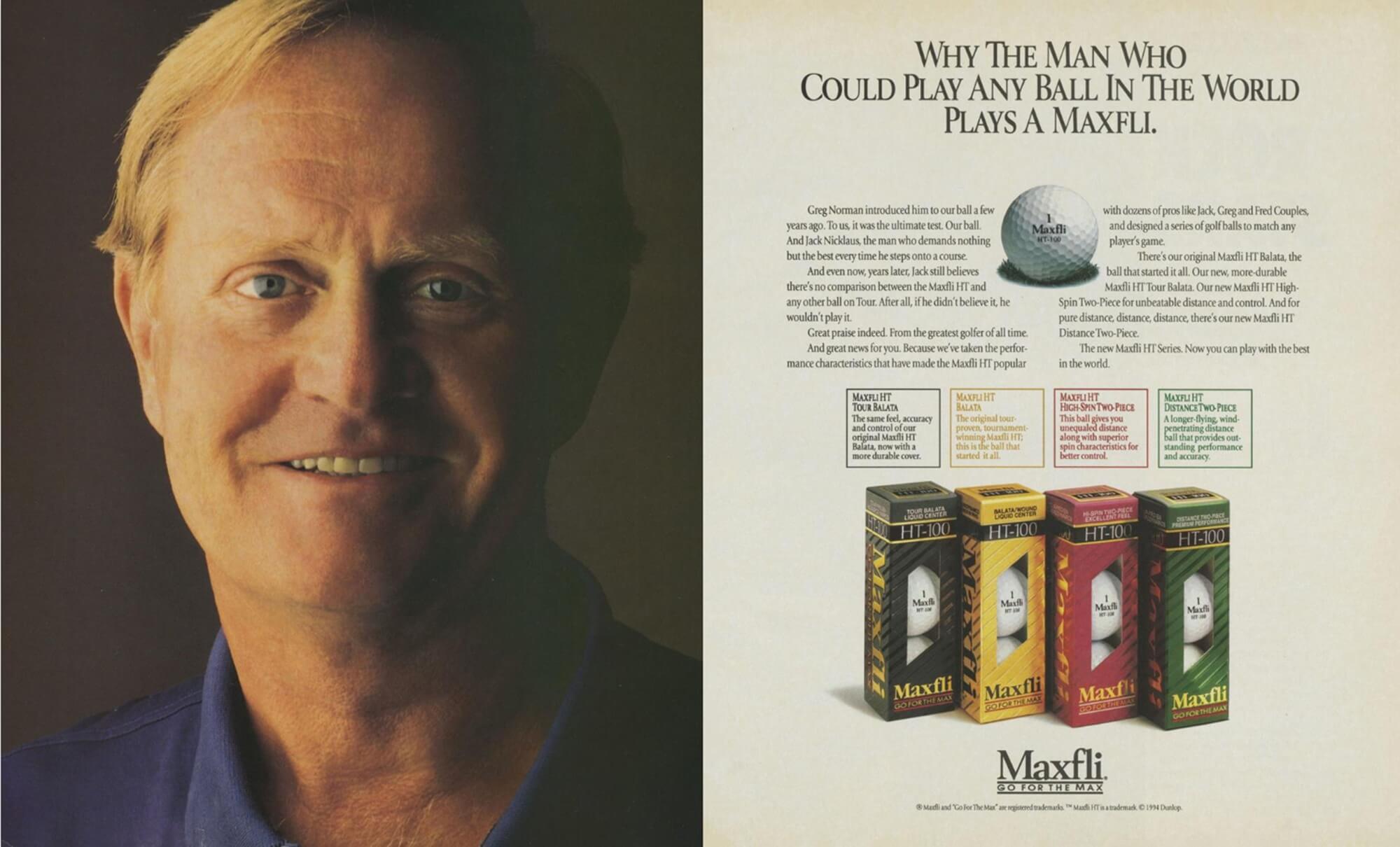

No one knew it at the time, but the balata ball was a dead man walking. Top Flite already launched the solid core, urethane-covered Strata, while Titleist was starting the Pro V1 project. The handwriting was on the wall, but no one was taking it seriously. However, on that January morning, the Maxfli HT Balata may have been the hottest ball in golf. World No. 1 Greg Norman played it. So did Fred Couples and Jack Nicklaus. In fact, just a few weeks earlier, Maxfli signed Tom Watson to play the ball. Maxfli trailed only Titleist in Tour play and the gap was closing.

Despite having a much smaller offering, Maxfli was a solid third in retail market share behind Titleist and Spalding. If you had opened up Golf Digest that morning, you’d have seen a full-page Maxfli ad that read:

Now the rest of the world can play with the best in the world.

At 5:46 a.m. on Jan. 17, the Kobe factory was an unstoppable machine. It had perfected precision rubber winding, latex balata dipping and climate-controlled curing. Balata balls weren’t easy to make and Tour pros were finding that the Maxfli HT Balata was every bit as consistent as the Titleist Tour Balata but with a softer feel and more spin around the green.

It was a ball made for shot makers.

Twenty seconds later, it all came crashing down.

Literally.

“The sound was like the earth itself was exploding”

The earthquake that hit Kobe that morning is infamous as the Great Hanshin Earthquake. The Kobe-Osaka area, some 330 miles southwest of Tokyo, is known as the Hanshin region.

It’s Japan’s second-largest urban area with a population at the time of more than 11 million.

The devastating quake registered 7.3 on the Richter scale. More than 6,400 were killed and tens of thousands more were injured. Nearly a quarter of a million homes were damaged or destroyed, along with more than 120,000 factories and industrial buildings. Rail lines were severely damaged, infrastructure was obliterated and Kobe’s port facilities were levelled.

The Hanshin Expressway, an elevated highway connecting Kobe with Osaka, collapsed.

In 1995 dollars, the total damage exceeded $200 billion.

Miraculously, no one at the Dunlop Kobe Factory was killed. The building itself and the delicate machinery inside, however, suffered significant damage.

In the immediate aftermath, making golf balls was well down everyone’s priority list. Maxfli officials, after assessing the damage, estimated it would be at least two to three months before the factory could be back online.

That estimate was wildly optimistic.

The Dunlop-Maxfli-Kobe connection

The historical links between the Dunlop Rubber Company and Kobe are a bit convoluted. Dunlop has its roots in Birmingham, England, where it started as the Byrne Brothers India Rubber Company in 1896. Four years later, it merged with the Rubber Tyre Manufacturing Company and was renamed Dunlop Rubber. As a proud representative of Queen and Country, Dunlop expanded, opening its Japanese operation in 1913. Its partner in rubber, a company which we’ll get to know better, was the Sumitomo Group.

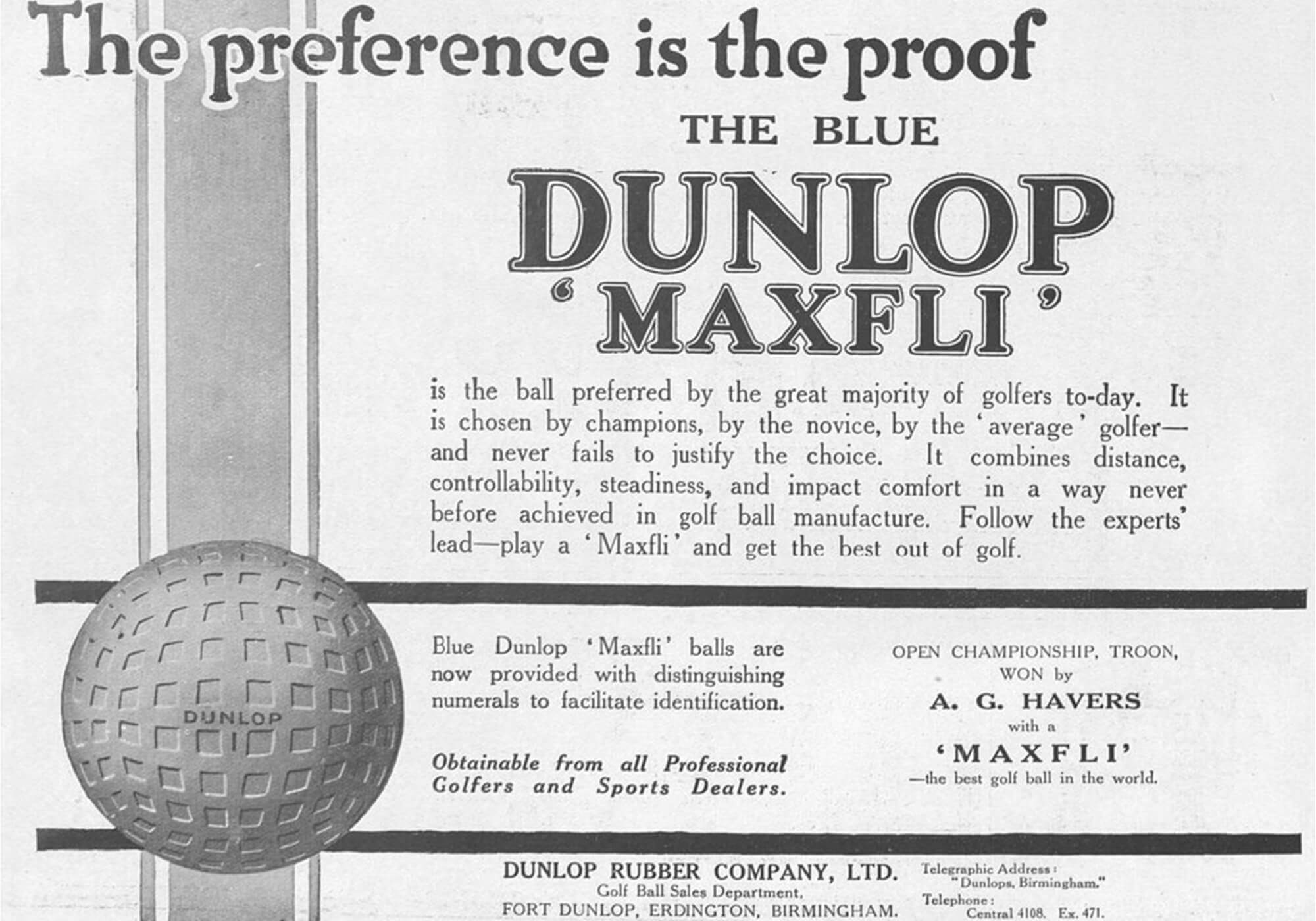

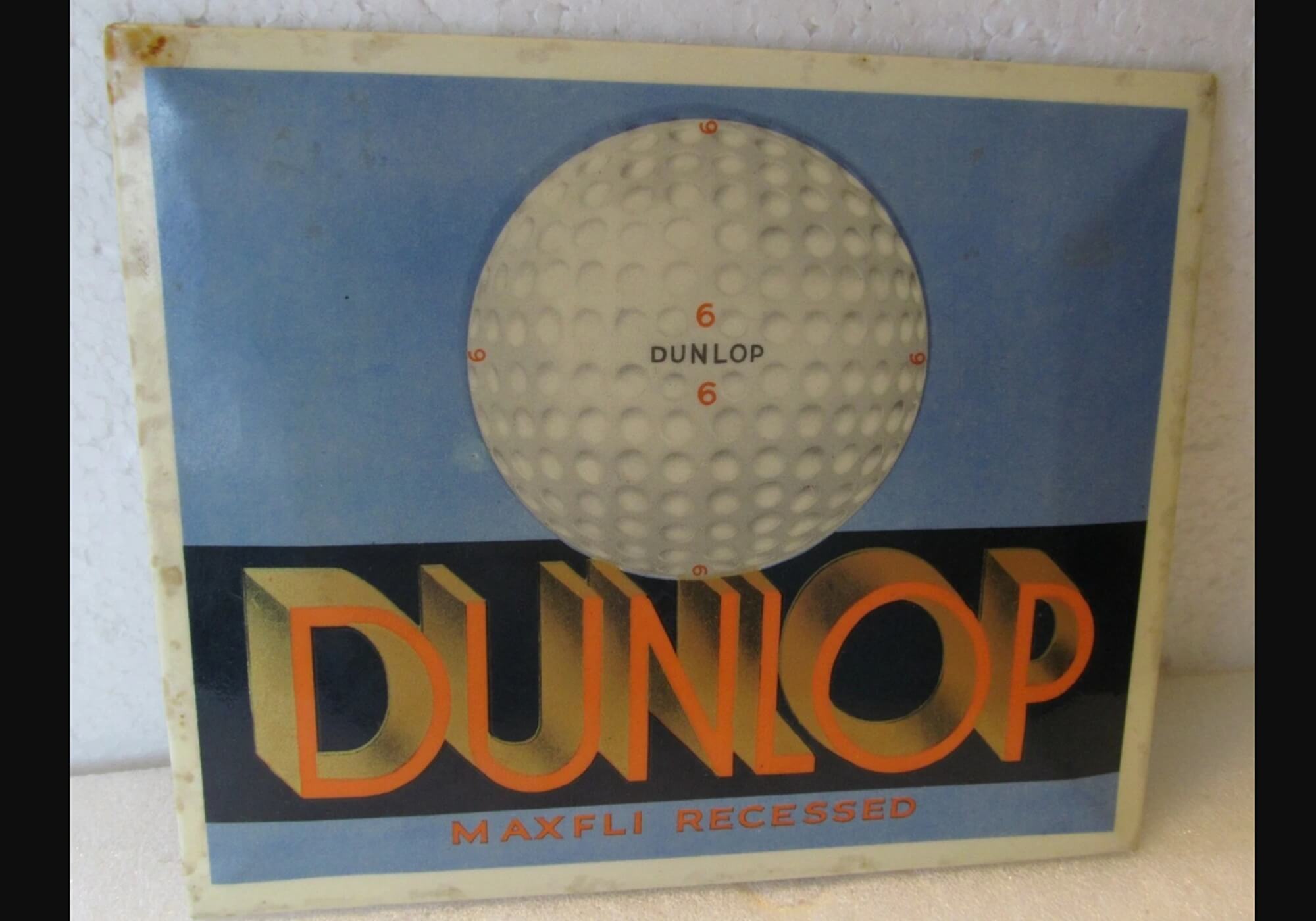

Back in England, a Dunlop rubber specialist named Albert Penfold designed and patented a revolutionary new golf ball called the “Maxfli.” It launched in late 1922 and blew away the market. By the time the Open Championship rolled around the following summer, 75 percent of the field was playing Maxfli, including eventual champion Arthur Havers.

Over the decades, Dunlop developed a habit of selling off regional rights to its local partners, usually during times of financial stress. That led to convoluted ownership with conflicting priorities. In 1963, Dunlop sold the Kobe factory and full control of Dunlop Japan to Sumitomo, which rechristened itself Sumitomo Rubber Industries. If that sounds familiar, it should. It’s the “SRI” in Srixon.

The immediate aftermath

Within a week of the earthquake, Maxfli knew it was in trouble. A shipment of HT Balatas for North America was already on the water when the quake struck but no one could predict when production would resume. The company quickly decided those balls would be prioritized to Maxfli’s Tour players. Retailers were told to expect severe shortages.

By Jan. 24, Maxfli Tour reps were warning players to use their existing stock carefully. “We don’t know when more balls will be coming,” one was quoted as saying. Some were actually encouraged by their reps to look at Titleist and Spalding as rumors started flying that the HT Balata wouldn’t return.

Those rumors weren’t unfounded. By March, engineers started assessing the damage to the Kobe plant and what they found was grim. Along with significant structural damage, the facility’s proprietary production equipment specific to wound balata manufacturing was ruined. Additionally, much of the skilled labor was displaced and the infrastructure needed to get raw materials in and finished products out was out of commission.

The earthquake didn’t just destroy the equipment; it destroyed the conditions required to make world-class golf balls. For all practical purposes, Maxfli was out of the balata business.

Maxfli might have been doomed anyway

The Kobe earthquake permanently halted Maxfli’s momentum. The factory did get back online later that year but output was dramatically reduced. Quality and consistency were never the same.

Maxflfi’s bigger problem, however, was that it was heavily invested in 60-year-old balata technology. By most accounts, Maxfli wasn’t yet on board with emerging solid-core and urethane technologies. The Strata launched a year earlier. A year after the quake, Titleist launched the Professional, a wound ball with a urethane cover. Behind the scenes, the Pro V1 project was already underway.

While Maxfli was trailing in solid-core technology, the quake did prompt it to act quickly. Now out of the balata game, SRI fast-tracked a new factory in Ichijima, about an hour northwest of Kobe. Within three years, Maxfli was able to patent and release its own solid-core urethane ball, the Revolution. By all accounts, it was a terrific golf ball as was the Maxfli A10 released in 2001. However, like Top Flite and the Strata, ownership challenges limited Maxfli’s success.

By the late ‘90s, Dunlop Slazenger was struggling. The company was already fractured by regional licensing agreements and conflicting ownership structures in Europe, Asia and the U.S. It was owned by British industrial conglomerate BTR which by 1996 had problems of its own. BTR sold Dunlop Slazenger to an internal management group backed by private equity money. Unfortunately, that stewardship didn’t go well. The company became nearly insolvent which led to the Royal Bank of Scotland taking over two years later.

Patents, distribution and TaylorMade

By 2003, the Pro V1 was firmly atop the golf ball market. Spalding/Top-Flite was months away from bankruptcy while NIKE was never able to capitalize on the Tiger Slam with the Tour Accuracy. Maxfli’s wobbly ownership, plus its patents on the Revolution and A10 (and two balls in development), made it a ripe acquisition target.

The Royal Bank of Scotland, wanting no part of owning a sporting goods company, put up the For Sale sign. TaylorMade, now under adidas ownership, was in a buying mood.

Maxfli already had a licensing and distribution deal in place with TaylorMade so the outright sale in January 2003 was a mere formality. TaylorMade now had solid-core urethane patents in hand as well as a substantial distribution network. The acquisition, along with hiring Dean Snell away from Titleist, thrust TaylorMade squarely into the premium golf ball game.

Maxfli’s last hurrah came soon. Shaun Micheel won the 2003 PGA Championship with an A10. The following year, Maxfli launched the premium BlackMax and RedMax balls. From that point on, however, TaylorMade turned Maxfli into its low-priced brand while all premium offerings would bear the TaylorMade name. By 2008, TaylorMade had no more use for Maxfli. It sold the carcass (it kept the intellectual property and the Noodle brand name) to DICK’S Sporting Goods.

History’s Mysteries: The legacy of the Kobe quake

The earthquake may have hastened Maxfli’s demise but the tea leaves were there for anyone to read.

Earthquake or no earthquake, Maxfli was on shaky ground in early 1995, even if no one knew it. Ownership was becoming a mess and wound balata technology was living on borrowed time. The Top Flite Strata showed us what a solid-core urethane ball could do while the wound Titleist Professional, with its shiny urethane cover, was the new #1 ball on Tour. Tiger shocked the world in 2000 with the NIKE Tour Accuracy. Titleist shocked it again with the Pro V1.

Maxfli, however, was fully invested in its existing wound balata production, right up until 5:47 a.m. on Jan. 17. The earthquake forced Maxfli to shift its focus. It still had some R&D juice and that new factory in Ichijima. That it could churn out the new Revolution and A10 as quickly as it did is nothing short of remarkable.

The problem, as is so often the case in these History’s Mysteries tales, wasn’t product. It was corporate. By the late ‘90s, Dunlop Slazenger was a pawn on BTR’s global chessboard and pawns get sacrificed. The management buyout seemed like a good idea at the time but the enterprise went south quickly. Once the banks take over, nothing really good follows.

For TaylorMade, Maxfli was a means to an end. Once that end was met, the brand was offloaded to DICK’S where it spent nearly a decade as the chain’s low-end house brand. That changed in 2017, however, when DICK’S launched the Maxfli Tour, a high-performing urethane ball that’s been the darling of MyGolfSpy readers ever since.

History’s Mysteries: A Maxfli footnote

Today, the Maxfli Tour golf ball line is a certified underground success. Last April, after 22 years, the brand finally returned to the PGA Tour winner’s circle when Ben Griffin won the Zurich Classic.

Additionally, Maxfli released its first real iron set since its last version of the iconic “Australian” blades in 1997. The forged Maxfli XC2 and XC3 were decent-enough performers in MyGolfSpy testing and, like Maxfli’s golf balls, are an excellent value.

As for Dunlop, remember Sumitomo Rubber Industries? Much of Dunlop’s convoluted global ownership can be traced to the 1913 Dunlop-Sumitomo partnership and SRI’s 1963 acquisition of Dunlop’s entire Far East operation. In 1973, SRI established Dunlop Sports Enterprises as a subsidiary. The Srixon brand launched in 1997 with XXIO launching three years later.

By 2003, SRI created an independent SRI Sports Ltd. which was listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 2006. SRI Sports bought Cleveland Golf in 2007 and it now operates under the Dunlop Sports Ltd. banner, leading the Srixon, XXIO, Cleveland and Never Compromise golf brands as well as Dunlop Tennis.

Oh, and that plant SRI opened in Ichijima? It’s now Srixon’s premium ball plant, making the Z-STAR line as well as Dunlop-branded balls for the Japanese market.

The post History’s Mysteries: How A Natural Disaster Doomed The Original Maxfli appeared first on MyGolfSpy.