Last Sunday night, Sean Payton sat in his office at the Denver Broncos facility, watching film of his opponent in the upcoming AFC Championship game: the New England Patriots. He wanted to have the Los Angeles Rams-Chicago Bears divisional round game on in the background. He turned on one of the flatscreens in his office. He flipped around, somehow ending up on Nickelodeon and “Dora the Explorer.” He finally found the right channel, just in time for the Bears to make a critical decision on their first drive. On fourth-and-two from the Rams 21, they elected to skip a gimme field goal and go for it — the exact type of call that has dominated playoff professional and college football this season, and can end up winning a tight game or be one of the main reasons for a loss.

Payton saw the Bears line up on offense, and he squinted. “Kick it,” he said.

On the play, Caleb Williams was intercepted, costing Chicago three points — the difference in the final score.

“Why are coaches not kicking field goals?” Payton said, turning back to game preparation.

That decision for coaches — when to go for it on fourth-and-short and when to kick — has become one of the most scrutinized and divisive calls in football, an easy sports talk debate. For most of professional football’s existence, it wasn’t even a decision. Coaches took the points. That started to change in 2002, when a renowned Cal-Berkeley economist named David Romer authored a paper called “It’s Fourth Down and What Does the Bellman Equation Say?”

Using the Bellman Equation — Ei Di(gt) Vi = Pgt + Bgt Ei Di(gt+1) Vi – egt — Romer’s conclusion was clear: the probabilities of what could happen after a successful conversion on fourth-and-four or less outweighed kicking a field goal or, in some cases, punting and playing field position. Simply put, the math told coaches to be more aggressive.

Romer’s findings didn’t become conventional wisdom for more than a decade. Now, broadcasts feature in-game analytics, with percentages. Coaches like Detroit’s Dan Campbell go for it as an imperative — as part of their identity.

The Broncos’ director of game management/assistant offensive line coach Evan Rothstein is one of Payton’s most trusted and valued staffers. He came to Denver from Detroit and New England, where he learned from Bill Belichick, who revolutionized situational football strategy. On Saturday mornings during the football season, Rothstein gives mesmerizing presentations to Payton and the coordinators, breaking down key moments from the previous week’s games and ending with data-backed opinions of what to do should the Broncos end up in a similar position.

But in the end, it’s Payton’s call.

Generally, if the Broncos are driving and faced with fourth-and-short yardage, they will strongly consider going for it. If it’s fourth-and-one after the opponent turns the ball over and gives Denver a short field, Payton will usually take the points.

Sunday’s AFC Championship was different, of course. It was different because quarterback Jarrett Stidham was making his first start of the season after star Bo Nix fractured his ankle last week. It was different because Denver’s defense hadn’t played particularly well since the bye week against top opponents. It was different because the Broncos could have easily lost to the Buffalo Bills in the divisional round because their red zone offense was inefficient: one touchdown in four trips. And it was different because a Super Bowl appearance was on the line. All of those facts can be used to argue for or against going for it on fourth-and-short.

In the second quarter on Sunday against New England, the Broncos were up 7-0. They drove into the Patriots red zone. On third-and-six, Stidham scrambled right for five yards to the New England 14-yard line. That left fourth-and-one — and a familiar decision. Denver had gained yardage on every play of that drive, and to that point, its defense had forced three punts.

“I wanted 14-0,” Payton later told me.

Going for it is one thing; finding a good play is another. Payton ordered 11 personnel — one running back, one tight end, and three receivers — and from it called a running play called Nickel Duo. “A sub-run versus a sub-front” he said.

Then, Payton called time-out. He wanted to think.

Duo was Denver’s top fourth-and-short run; Slipper Naked, a bootleg to the right, was its top fourth-and-short pass. He went with the pass. But at the snap, the Patriots surprised Denver by playing Red Two, a zone defense, behind a six-man front. The play had no chance. Stidham threw into traffic, incomplete. Denver not only missed out on three points, it missed out on its last, best opportunity for easy points. The Broncos never got so close to the end zone the rest of the game.

“I wish I’d stayed with the initial play call,” Payton said softly, leaving the stadium. “The look they showed on film, and the look we saw, wasn’t the look we got.”

The Broncos, the AFC’s top seed and a home underdog for both playoff games, lost for many reasons. They failed to run, and catch, well. They missed two field goals. Stidham fumbled in the second quarter, leading to New England’s only touchdown, and threw an interception late the game. Denver’s defense played one of its best games of the year but forced zero turnovers. A priority all week — both in coaches’ game-planning sessions and full-team meetings — was to contain quarterback Drake Maye and keep him from running. Maye ended up with ten carries for 65 yards and a touchdown, including a run left to ice the game with just under two minutes left.

But Denver also lost because of Payton’s decision. Something about fourth down brings out the explicable and inexplicable in coaches, the rational and irrational. You never know what you’ll get. To this day, Belichick regrets going for it on fourth down against the New York Giants in Super Bowl XLII. In Sunday’s NFC Championship against Seattle, Sean McVay of the Rams — a coach who is often criticized for not going for it on fourth down enough, and who took field goals against Chicago last week and won — went for it twice on fourth down midway through the fourth quarter down 31-27, getting a first down on one, missing the second time, and coming away with zero points in the loss. Why do some fourth downs convert, and some fail?

Payton hates it when people attempt to rationalize a missed opportunity or failed play by shrugging and saying, “That’s football.” It’s an affront to his soul and everything he stands for, when he and his staff work 18-hour days to impose their will on a coin flip of a game.

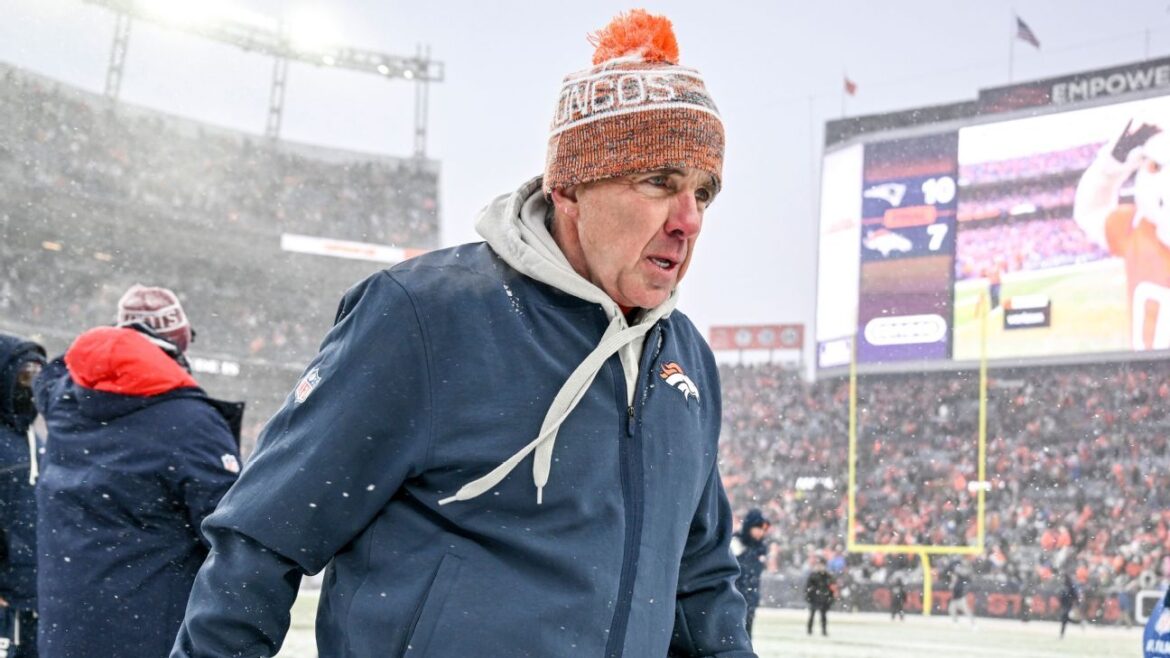

But the thing is, that is football. And always will be. After Sunday’s game, Payton entered his small office down the hall from the locker room. He sat down and stared at the floor. He is 62 years old and has been a head coach for 19 years. He has a Super Bowl win, and many devastating playoff defeats. It was quiet, except for the random sounds of the crash landing of a season ending: the echo of a shouted cuss word, the shuffle of coaches and staffers mulling around and whispering.

Moments passed. Payton sat up.

“I can’t believe we lost.”

A few more seconds passed.

“That fourth down …”