From Water to Ice, Carsten Vissering Set to Realize His Olympic Dream

Carsten Vissering’s dreams still bring him back to the swimming pool now and again, even if his body has brought him a much different – and previously unimaginable – kind of Olympic dream.

This March will mark seven years since Vissering’s last swim meet, the culmination of a career that brought NCAA medals and a national high school record. Devoted to the sport full-time from age eight onward, he aspired to reach the pinnacle that is the international stage, maybe even an Olympic team.

His swimsuits have been hung up for a while, but Vissering still dreams of swim practices. The settings are familiar – USC, where he was an All-American, Georgetown Prep and Nation’s Capital Swimming. But the cast of characters is new.

“I’ve been doing this for about four years and trying to make it on a different team, but I still have dreams where I’m at swim meets,” Vissering was saying recently. “The weird thing is, I’m with my bobsled teammates.

“I don’t have bobsled dreams. I have swim dreams, still.”

“Surreal” is a word that the 28-year-old regularly brandishes. He ended his aquatic career in 2019 still hungry for some kind of physical competition but burned out on swimming. The physical challenges he relished – weightlifting, explosive training – pointed him in the direction of bobsled in 2022, a career he entered with no aspirations beyond a novel way to challenge his body.

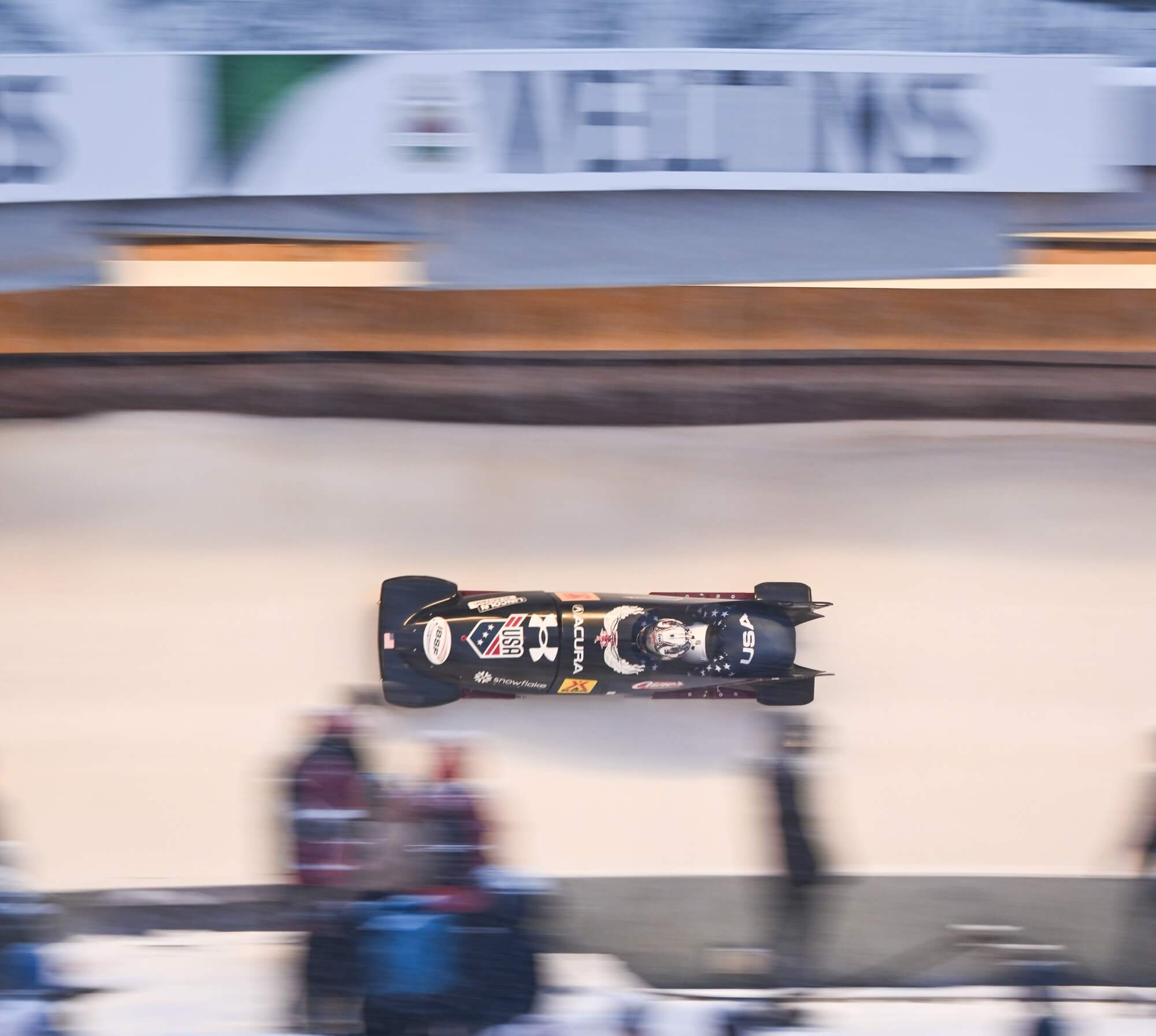

Three years later, the career-defining accolade he once dreamed of occurring on a pool deck in Indianapolis or Omaha occurred in a hotel conference room in Europe. The water on which he plies his trade is now frozen, sculpted into the side of a mountain and traversed in a hyper-engineered sled crammed with 800 pounds of muscle.

Vissering will realize his Olympic dream this week at the Milan Cortina Winter Games as a push athlete for the U.S. bobsled team, in the four-man competition and likely the two-man. It’s the realization of a dream that Vissering couldn’t even quite articulate when he started in the sport, and a culmination of many decades of work to put him in this unique position.

“I’m going to the Olympics for a different sport, but I still haven’t the swimming identity so deeply ingrained in me,” he said. “And it’s just surreal that, I guess the goal was hit, but it’s not through swimming.”

Out of the pool …

Vissering wasn’t just any swimmer in his achievements in the water. Out of it, he still wears the moniker of “that weightlifter who swims” with pride.

Carsten Vissering at NCAAs in 2019 for USC; Photo Courtesy: Peter H. Bick

Vissering was one of the top recruits in the high school class of 2015. The native of Bethesda, Maryland, set a national age-group record in the short-course yards 100 breaststroke and that event’s national independent high school mark. He swam at the World University Games in 2015 in Gwangju, South Korea, finishing eighth in the 50 breast, 21st in the 100 breast and swimming in prelims for a U.S. men’s medley relay that won silver. He landed that fall at USC in a training environment under coach Dave Salo, known for his unusual approach to building power and strength, that seemed perfectly suited to the loads Vissering was willing to take on in training.

His time in the weight room translated to times in the pool. As a freshman, he was an NCAA B finalist. As a sophomore, he was a Pac-12 champion in the 100 breast. He won an NCAA relay title in 2018, then followed two bronze medals at NCAAs in the 100 breast with silver in 2019 as a senior as well as a second Pac-12 title in that event.

His career was left open-ended in 2019. He still wanted something to stoke his competitive fires. But after NCAAs, if that was going to be swimming again, he needed a mental and emotional reset through the summer. “I was pretty burned out on swimming,” he admits. As he pondered training on through Olympic Trials in 2020, he felt like he was going through the motions for other peoples’ expectations rather than his own desire. By the time COVID-19 descended and the 2020 Olympics in Tokyo were postponed, he was all the way out.

But in trying to find his way post-swimming, he’d discovered other physical outlets. As much as he was drained by the mental process of toiling to drop hundredths of a second in the pool, he remained eager to get to the gym every day, to see how much more weight he could lift, how much further he could jump and how much more power he could generate on land.

“Every year, I got stronger and stronger,” he said. “And I really developed a love for the weight room, which I still have.”

That love was the guiding force. It wasn’t so much what he was training for as the training itself. If swimming had become too results-oriented, then focusing solely on the process sounded was an escape. And maybe one day something would come along that united all those new talents he was cultivating.

“I knew I had some things special in the power department,” he said. “I put up a 42 and a half inch vertical jump. I was into stuff like the broad jump or the vertical jump and the clean, and I was like, Oh, wow, I’m putting up numbers that are competitive at the NFL Combine right now. So I think I’ve got something.”

… And into the sled

Swimmers do not become bobsledders. That was the message Vissering got pretty soon into his transition to the ice.

The message was polite. And it was solicited when Vissering saw what a push athlete’s job entailed and asked around about the possibility of making the leap. It was also authoritative, from a former national team member turned sports performance expert who laid bare the biomechanics.

Carsten Vissering, rear, and pilot Kris Horn at a World Cup two-man bobsled race; Photo Courtesy: IBSF

“He said, I’m going to be honest with you: You’re not going to go far in this sport,” Vissering likes to recall. “You don’t have the tools or the qualities that you need to be a world-class bobsledder and make the national team or the Olympic team.”

That message reflected the averages. Push athletes require short, immensely powerful bursts to get the sled up to speed, then get aboard and serve as ballast. It’s all-out exertion for 50 meters and a little over five seconds, then enough grace to board the sled and fold into position.

Perhaps the most famous Olympic bobsledders are football player Herschel Walker and track and field athlete Lolo Jones. Those sports are where USA Bobsled and Skeleton derive many of their athletes: The team for Milan Cortina is rife with track athletes, among them decathletes on the men’s side and an NCAA indoor heptathlon champion on the women’s in Jadin O’Brien.

Vissering understood the initial pessimism, even while professing to be a different kind of swimmer. It’s also partially why he came into the sport with limited expectations.

“I wanted to do it more so with an exploratory view, like, let’s try this out,” he said. “I just finished my whole life swimming, and I’m young and athletic. You want to try these other things.”

Vissering got his foot in the door in the fall of 2022, with the program in refresh mode after a lackluster Beijing Olympics for the men. (The American two-man sleds finished 13th and 27th out of 30 competitors; in the four-man, 10th and 13th were the best the U.S. could muster.) Fall combines are a chance for USABS to cast a wide net, looking for new and athletic blood.

Vissering finished fifth at his first push championships out of 18 competitors. It earned him a spot on the World Cup circuit, and he went down the track for the first time in Park City, Utah, that winter, an “incredibly intense” ride subject to g-force loads he’d never experienced before.

“It’s a contact sport,” he said. “It’s not the most pleasant ride. It’ll give you a huge adrenaline rush.”

Vissering rose to third among push athletes at the 2023 Push Championships against a considerably deeper field. He was second the next year.

After years as a sprint breaststroker, spending hours upon hours trying to trim hundredths of a second off his time, Vissering was suddenly seeing rapid improvement. He started as a blank slate. The rush of setting personal bests was intoxicating.

“Everything is so new,” he said. “You’re seeing so much improvement. The development and these traits is in itself is something that hugely motivated me, and I think that helped me make this transition so fast and successful.

“Training for me was not a chore. I love everything about sprinting. I love weightlifting. I love jumping. It’s easy for me to train at this high level intensity that probably would burn a lot of people out. And I think that’s that was one of the critical factors that really helped with the transition.”

His body is much changed from his swim career. But one trait remains unexpectedly valuable. All those years of breaststroke have endowed 6-5 Vissering with unusually flexible hips. The downside to all that power at the top of the hill is that the muscles powering it have to be stowed aerodynamically for the ride down. A position where, “you sit on your butt with your legs straight, then hold the frame near your ankles … and when you go through the pressures, your head will kiss your knees” is not something every body is capable of. Vissering’s is, and he points to swimming as a possible reason why.

Onto the Olympics

By the dawn of the Olympic season in the fall, Vissering had established himself as a front-liner for USABS. He spent much of this season behind top American pilot Kris Horn, in both two-man and the second seat in four-man. As a duo, they finished fourth at a World Cup race in Winterberg, Germany. The four-man sled had four top 10s, including seventh in the Cortina Olympic course in November and sixth in Lillehammer in December.

Vissering was also involved – albeit in absentia – in the program’s highest-profile moment of the season. Horn and Vissering crashed in the two-man race in St. Moritz in January, the sled tipping and the taller Vissering getting a raw ride down the ice that left third-degree burns on his left shoulder nine days out from Olympic selection. As of late January, he was healing fine and on course for Milan Cortina.

But he wasn’t in the four-man sled the next day. His replacement, Ryan Rager, stumbled at the top, setting off a chain reaction that led Horn to have to pilot the sled by himself down the track. Or more accurate from a physics perspective: Horn, minus the 600 pounds usually seated behind him to weigh down the sled and give the runners purchase on the ice, was along for the ride as a half-as-heavy sled careened down with minimal steering. Horn’s shimmy from the driver’s seat to the rear brakeman’s cables at the end of the course – there are no brakes, just steering pulleys at the front – was the last death-defying maneuver by the pilot to save the sled in what became a viral video moment. Coaches and crew on course in Switzerland let out a palpable sigh of relief when the sled stopped in a sport that can (albeit rarely) turn deadly.

“You immediately think about the safety of the pilot, because the sled, it changes its maneuverability when you have 600, 700 pounds of men not in the sled, and that will change the steering,” said Vissering, calling it a “worst-case scenario.” “You could probably tell in the video, it was very squirrely. And I’m like, well, if he crashes, he’s about to get really messed up.”

Horn and the sled survived. Without Vissering, the Americans had a forgettable final World Cup race in Altenberg, Germany, the next week. But the following Monday, he was among eight men named to the Olympic team, in his usual spot in Horn’s four-man sled. (Two-man pairings are yet to be announced.)

Two-man training in Cortina begins Feb. 12. The first two of four runs in the two-man are Feb. 16, with the last two and medals handed out on Feb. 17. Four-man practice opens the next day, competition running Feb. 21-22.

Vissering will be there, a long way from a pool but not from his swimming identity.

“It’s so surreal still,” he said. “It still hasn’t really hit me.”