Carlsen’s third SCC title in a row

The finals of the Speed Chess Championship 2026 were staged in London, marking the second occasion on which the concluding phase of the largely online competition has been held before a live audience. Last year the finals took place in Paris – this time the organisers, chess.com, brought the event to the British capital. On both occasions, Alireza Firouzja reached the final and faced Magnus Carlsen for the title.

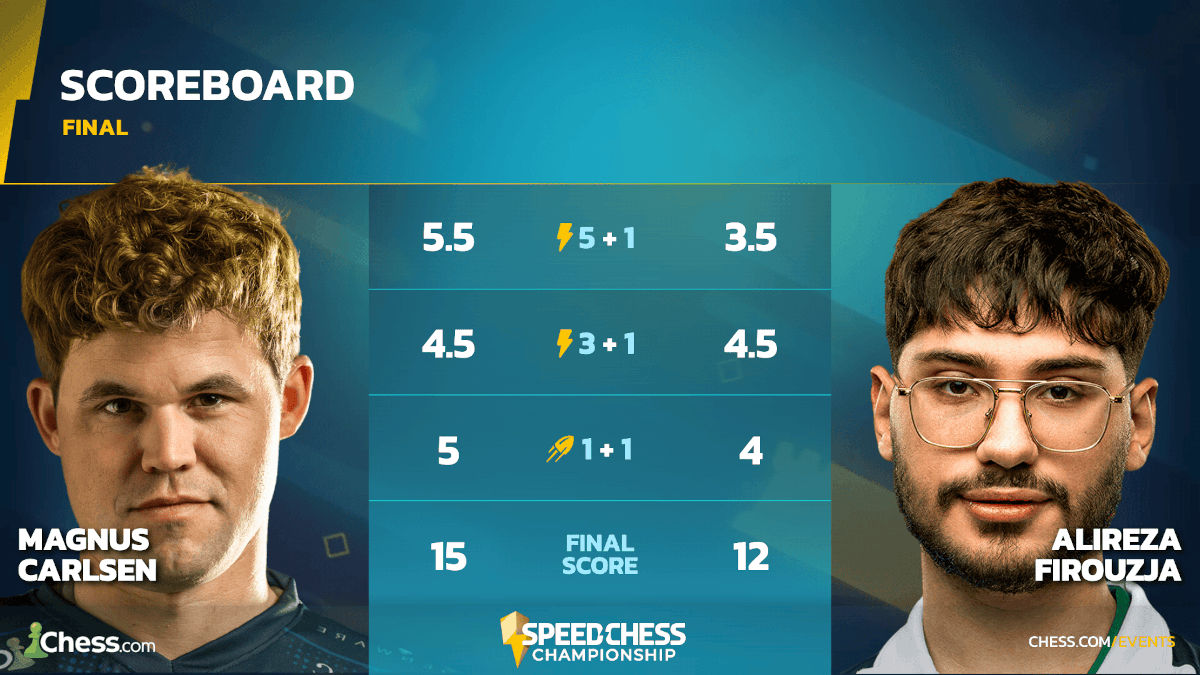

Carlsen secured a 15–12 victory to claim the championship for a third consecutive year. In contrast to the previous live final in Paris, where he scored a one-sided 23½–7½ win, this year’s match was competitive throughout.

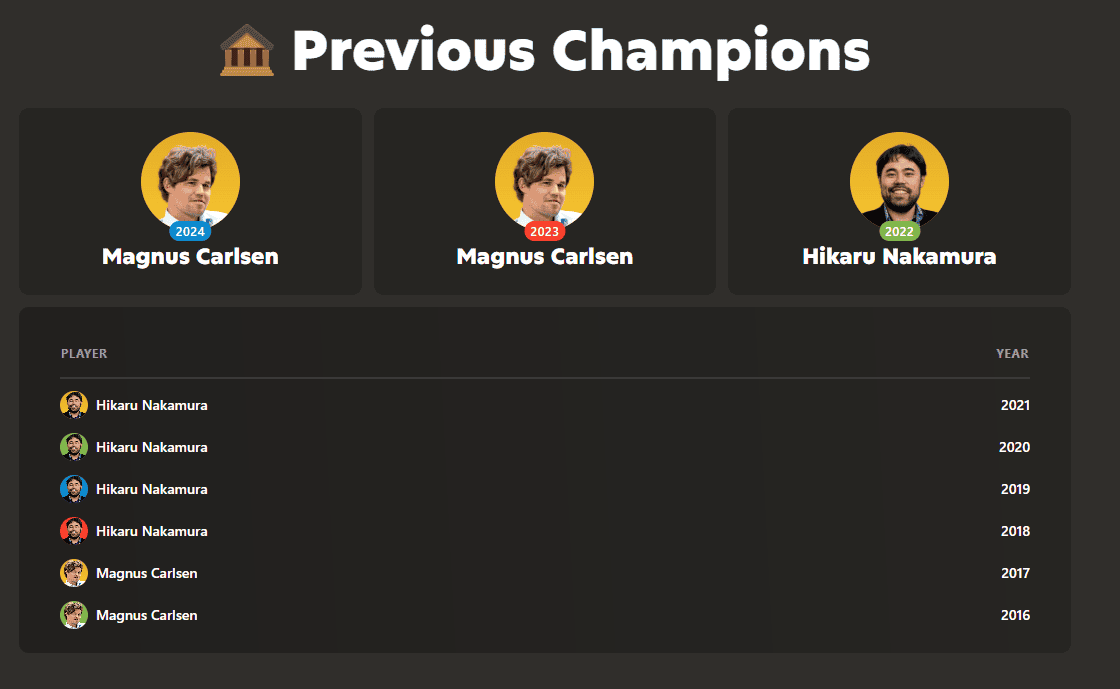

The Speed Chess Championship has now been held ten times, and only Carlsen and Hikaru Nakamura have ever lifted the trophy. With this result, both players stand on five titles each. Carlsen’s latest triumph further underlines his sustained dominance in the format, which combines 5-minute, 3-minute and 1-minute games in a structured setting that has helped professionalise online speed chess, long a staple for a vast community of amateur players.

Firouzja arrived in the final after a lengthy and demanding semifinal against Nakamura, and he began the title match confidently. In the first 90-minute segment at a 5+1 time control, he won games five and six to take a temporary lead. Carlsen, however, responded with three consecutive victories, regaining the initiative and closing the opening segment with a two-point advantage. The momentum of the match shifted decisively at that stage, even though the margin remained within reach.

The second segment, played at 3+1, proved evenly matched. The players scored two wins each and drew the remaining five games, producing a 4½–4½ result for the hour.

In the penultimate game of the 3-minute segment, Carlsen calculated that he would win a king and pawn endgame, and invited the live crowd to cheer once he had seen the forced line that led to his victory

In the very next game, Carlsen blundered and lost from a balanced position – as usual, he did not hide his frustration

Firouzja, who is thirteen years younger than Carlsen, had already demonstrated in his semifinal victory over Nakamura that he could overturn a two-point deficit in the bullet phase. Entering the final 1+1 segment two points behind, he still had realistic chances of mounting a comeback.

Carlsen, however, immediately extended his lead by winning the first game of the 1-minute portion, moving three points clear. From that point onwards, the contest stabilised. The finalists exchanged victories with the black pieces – three wins apiece – and drew two further games. With neither player able to produce a decisive late surge, the match concluded 15–12 in Carlsen’s favour.

This year’s edition introduced the Daniel Naroditsky Cup, named in honour of the late American grandmaster who was closely associated with the event and was greatly appreciated within the speed chess community.

Naroditsky’s name will now be permanently linked to the championship. The trophy will carry the names of all past champions, added retroactively, and future winners will likewise be engraved, ensuring continuity between previous and forthcoming editions.

The Daniel Narodisky Cup | Photo: chess.com / Luc Bouchon

All games

Lazavik stuns Nakamura

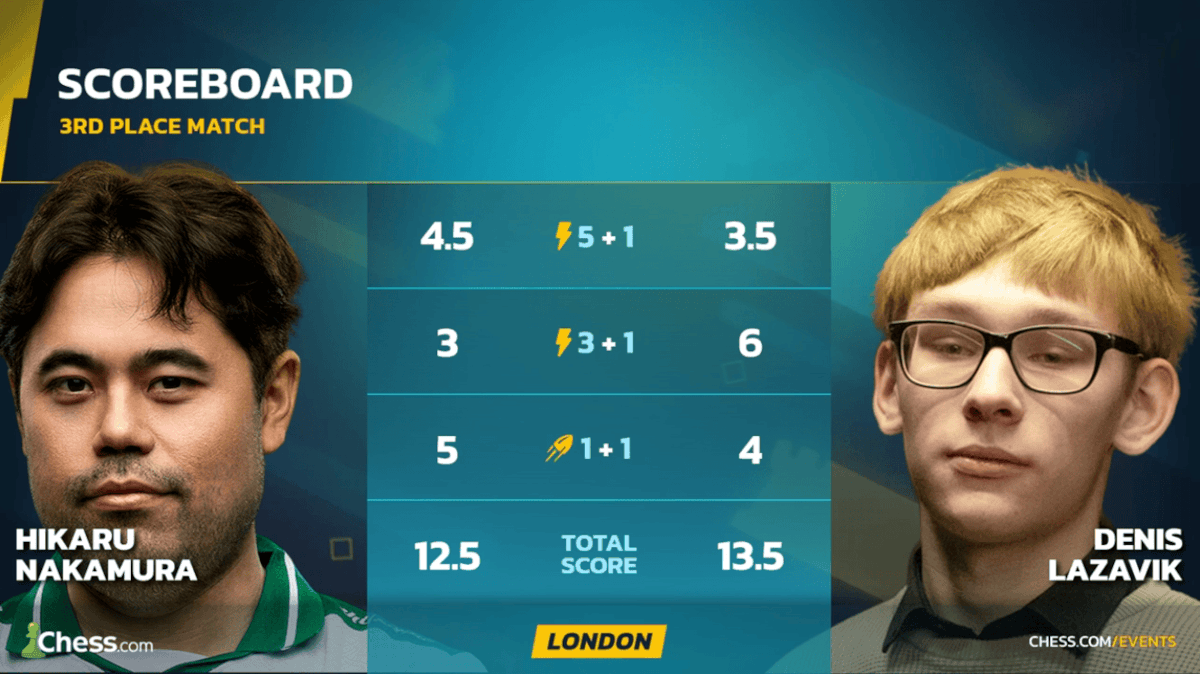

Earlier on the same day, Hikarua Nakamura and Denis Lazavik contested the consolation match for third place. In a notable result, the 19-year-old Belarusian defeated the more experienced Nakamura by 13½–12½.

Nakamura took the 5+1 phase 4½–3½, establishing an early edge. Lazavik then produced a commanding performance in the 3+1 segment, winning it 6–3 and overturning the deficit to carry a two-point lead into the 1+1 portion.

The bullet segment began with two draws. Lazavik then won the third game, extending his advantage to three points. Over the next five games, however, Nakamura fought back, winning twice and drawing the other three. This sequence left him entering what would prove to be the final game of the match with practical chances of levelling the score.

The King’s Indian Defence has been one of the most dynamic and popular responses to 1.d4 for decades. Legends such as Garry Kasparov, Bobby Fischer, and Hikaru Nakamura have employed it at the highest level – and it continues to fascinate today, as it offers Black not only solidity but also rich attacking and counterattacking opportunities. Its special advantage: the King’s Indian is a universal system, equally effective against 1.d4, 1.c4, and 1.Nf3. Grandmaster Felix Blohberger, multiple Austrian Champion and experienced second, presents a complete two-part repertoire for Black. His approach: practical, clear, and flexible – instead of endless theory, you’ll get straightforward concepts and strategies that are easy to learn and apply.

Free video sample: Introduction

Free video sample: London System

In the middle of that last encounter, the segment time expired. Under the championship regulations, any game that has already begun before the timer runs out is counted towards the final result, regardless of whether it finishes after the time control has technically ended. In the position on the board, which was close to objectively equal, Nakamura allowed a perpetual check, thereby confirming Lazavik’s overall victory.

Nakamura misunderstood the application of the rules, as in a typical bullet situation, he would almost certainly have continued pressing in search of winning chances. As it happened, the draw by perpetual gave Lazavik overall victory.

Already a well-known figure in the online chess scene, Lazavik later remarked, “He’s a very strong opponent, so I’m very happy to win”.

Denis Lazavik signing autographs | Photo: chess.com / Luc Bouchon

“Denis the Menace!” | Photo: chess.com / Luc Bouchon

All games

Doesn’t every chess game get decided by mistakes? Absolutely. But most players never truly comprehend that they are making the same kind of mistakes over and over again.