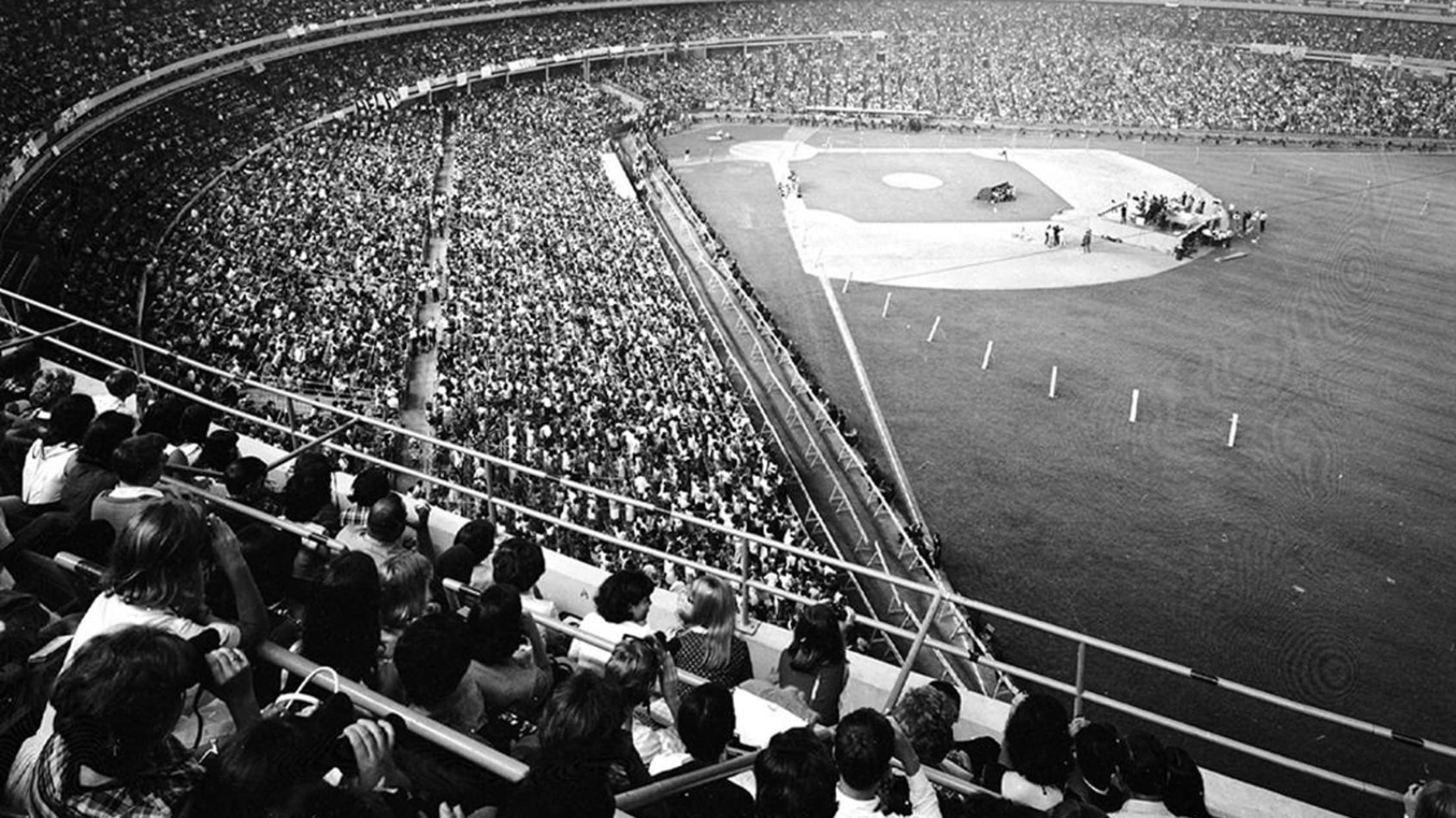

It was an August night in 2006, and an aging Shea Stadium was packed. Standing behind a podium near second base, Mets radio voice Howie Rose looked back at the crowd, the more than 57,000 fans celebrating the 20th reunion of the World Series champion 1986 Mets. But his mind was on a different August night at Shea.

“This is not only exactly where the Beatles were [in 1965], where the stage was [at second base], but as I’m looking into the crowd from my vantage point, I’m seeing exactly what they saw,” Rose recently told MLB.com.

“I couldn’t escape it. I’m introducing all these players, many of whom are friends of mine. I’m trying to talk them up and say nice things, but all I could think of is, ‘This is where the Beatles were.’ It was incredible.”

Friday marks the 60th anniversary of a watershed moment in the shared history of the Beatles and the Mets’ former longtime home. It’s a moment that completely redefined the entertainment industry while putting the venue of the worst team in baseball at the time on the international map for perpetuity.

“It was terrifying at first when we saw the crowd,” George Harrison said after the show. “But I don’t think I have ever felt so exhilarated in my life.”

Years later, after the Beatles’ breakup, John Lennon was even more effusive and conclusive, telling the concert’s promoter, Sid Bernstein, “At Shea Stadium, I saw the top of the mountain.”

By the time the Beatles took the stage before a then-record 55,600 fans for a performance that was filmed for television and posterity, they were already atop one of their many peaks of massive popularity — Beatlemania in the United States exploded after their landmark Ed Sullivan Show appearance in February 1964 as they collected three No. 1 albums, a half-dozen chart-topping singles and two blockbuster films in the period between then and mid-August 1965.

Yet, despite the commonly held gospel claiming their show at Shea Stadium — which opened its gates two months after the Fabs’ first U.S. visit in ‘64 — was the origin of the large-scale stadium gig, it wasn’t even the first Major League ballpark played by the group.

Eager to bring the Beatles to Kansas City, maverick Athletics owner Charlie Finley lavished the band with $150,000 — triple their usual payday — to perform on a scheduled day off during their 1964 tour amid an A’s East Coast road trip. Finley absorbed a steep loss as the Beatles first performance at a ballpark drew just over 20,000 fans, about half of Municipal Stadium’s seating capacity for the show and a fraction of the eventual Shea audience.

The 20,000 figure was about the same crowd the Beatles drew to a hurricane-torn and controversy-laden appearance at the Gator Bowl on that same ’64 tour, and not much off the 26,000 that saw Elvis Presley at the Cotton Bowl in 1956.

The struggle to fill the stands in Jacksonville and Kansas City likely led to Beatles manager Brian Epstein’s initial hesitation to book the band at Shea. But Bernstein, who previously brought the Beatles to a sold-out Carnegie Hall, felt certain he could sell out the stadium, even if history wasn’t a guide.

Bernstein first worked with Mets VP James K. Thomson to schedule a 1965 date at Shea — at one point cautioning he could pursue staging a show at Yankee Stadium instead if they couldn’t come to terms, according to the promoter’s memoirs. Once the August date and associated payment terms were secured — $25,000, plus insurance, security and the stage construction guaranteed by Bernstein for the rental of the park — he turned to Epstein to finalize arrangements.

Tickets ranged from $4.50 to $5.65 — by comparison, Mets tickets in 1965 cost from $1.30 to $3.50 — and Bernstein alleviated any fears Epstein had of another half-full ballpark by promising to pay $10 for any unsold ticket, he was that confident of the inevitable sellout. Sure enough, primarily based on word-of-mouth alone, the show sold out long before the summer, stuffing Bernstein’s PO box with cash and checks from around the globe en route to grossing $304,000, of which the Beatles earned $150,000. (For context, MLB’s highest paid player in 1965 was Willie Mays, who reportedly made $105,000 for the Giants on the season).

It was very big and very strange.

Ringo Starr on Shea Stadium

Shea Stadium was always huge. When it was built, it had the fourth-biggest capacity in baseball, and it was third-biggest when it closed in 2008. Today, Dodger Stadium is the only park with a bigger capacity.

“It was just cavernous,” Keith Hernandez said in the 2008 documentary Shea Goodbye. “You could see forever.” In the same documentary, Tom Seaver agreed: “The first time I saw it, it was so big and so huge.”

Ringo Starr shared those reflections decades after the show. “If you look at the film footage you can see how we reacted to the place. It was very big and very strange.”

Shea Stadium, as pictured on Opening Day 1964 (AP)

Owned by New York City and operated by the Parks Department, the Mets were always Shea’s primary tenant, but from the outset, the stadium was designed as a multiuse facility with the Jets née Titans calling it home from 1964-1983 and other events expected in the future, like large-scale concerts.

“Show business is coming to the home of the Mets,” said a New York Daily News report from April 1, 1964. “[I]t is expected to return some of the whopping investment the city has made in the new ball park.” Contemporary newspaper reports speculated Frank Sinatra eyed a date at Shea in summer 1964.

Adorned in gleaming blue and orange metal sheets on its exterior, the ballpark was distinctive and modern.

“When it opened — and people are very dismissive of this among those who saw Shea in its latter days – but Shea was state of the art when it opened,” Rose said.

Shea Stadium, with its hanging metal decorations, as pictured in November 1973. (AP)

A cutting-edge ballpark couldn’t turn to a 49-year-old Frank Sinatra in the age of rock and roll if you’re making a statement in scheduling a debut concert. If ever there was a bridge to the present day and the future, and if you’re looking to set a precedent and fill stadium, it could only have been the Beatles.

If the baseball world knew and courted the Beatles, the Beatles knew little of baseball.

On their first trip to the U.S., before playing in Kansas City, Ringo described the sport as consisting of “[throwing] the ball, and then another 10 minutes you have a cigarette and throw another ball.”

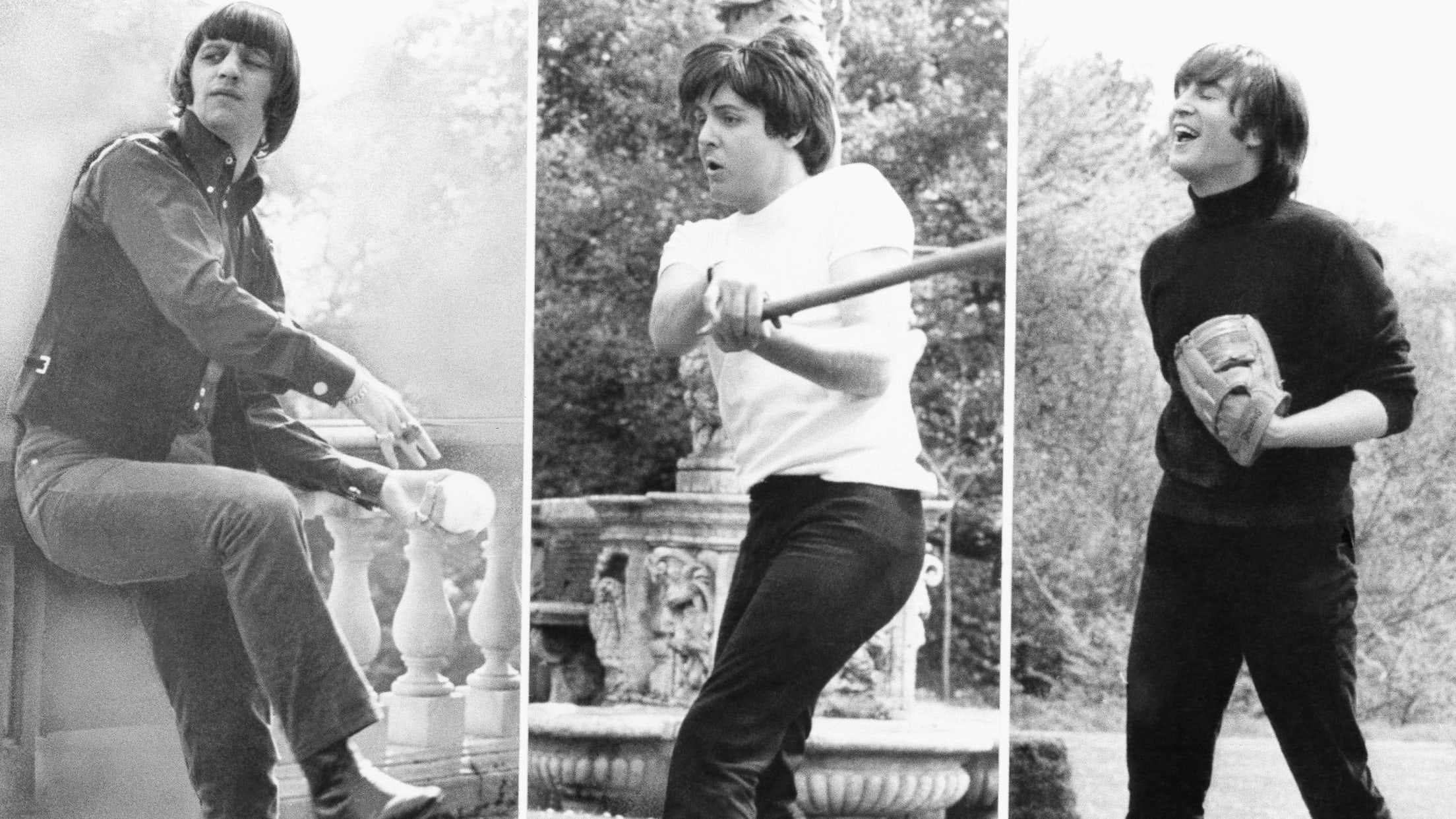

They didn’t learn much more about the game in the months prior to playing Shea.

“We’ll be doing a couple of rounds of baseball before we go on, just to limber up,” Paul McCartney told a Brooklyn radio station in May 1965. “Is that what you call it? ‘Rounds’ of baseball? Maybe not.”

“A square of baseball,” Ringo quipped.

A day or two after that interview, in a break during the filming of Help!, John, Paul and Ringo were photographed at a park outside London — Ringo pitching with what can be generously described as a unique grip, Paul flailing at a pitch with a skinny bat and John laughing with a baseball glove on his hand. (In a scene in the film presumably shot that day, Paul is seen awkwardly flipping a softball into a mitt while the others play cards).

Ringo, Paul and John, as pictured in mid-May 1965 (AP)

Good thing these guys had something to fall back on when they finally made it into Shea Stadium on the night of August 15, 1965, an evening that was simply staggering by any measure.

The Beatles concert wasn’t young Shea’s biggest crowd. The Mets already drew 57,175 for a doubleheader against the Dodgers two months before the show. In the nightcap, a controversial call went against the Mets, leading to chaos in the stands as fans pelted the field with debris while stadium police moved to break up more than a dozen fights.

How will I ever enjoy a Met game again?

A baseball fan protesting the Beatles’ appearance at Shea

Clearly, concert crowd control was a priority, and 2,000 security personnel were put in place — police, ushers, and 40 karate black belts — and three sets of barricades set up between the 55,600 Beatles fans and the field. Ultimately and inevitably, some fans were able to break through some layers of security, but they didn’t get particularly far.

“We spent weeks drawing up plans, as if they were battle plans, trying to ensure the Beatles’ safety,” Bernstein wrote.

Not everyone thought a multiuse stadium should have multiple uses. A wire report noted two young men from “Associated Lovers of Baseball Against the Ruination of Shea Stadium (ALBATROSS)” protested outside before the show.

“The Beatles playing in Shea Stadium is like a burlesque show in church,” one of the two protesters told UPI. “How will I ever enjoy a Met game again?”

The park was already packed as the Beatles arrived from their Manhattan hotel to Queens via helicopter, landing on the roof of a building at the adjacent World’s Fair in Flushing Meadows after Epstein’s aspirational plan of a grandiose landing on the field at Shea was rejected.

Shea Stadium (top) sat in close proximity to the 1964 World’s Fair (which closed in October 1965) (AP)

The group made its way into at Shea via Wells Fargo armored truck guarded by 60 policemen — the band was gifted the bank’s star-shaped badges that they wore on their beige military-style jackets, completing what became an iconic look unique to this night.

While several opening acts performed to the impatient audience — they were the true canaries in the coalmine, the first performers in front of an historically gigantic audience — the Beatles got ready in the umpire’s dressing room, one last occupied by the likes of future Hall of Famer Al Barlick before the Mets left town the previous week. In that space, they sketched out their 12-song setlist on a discarded scorecard.

While the crowd created a constant drone of screams that started hours before the gates even opened, “the boys were unusually quiet,” on the day of the show, roadie Mal Evans wrote in his diary — he also noted how much this show meant to the band.

Before heading to the field, the Beatles made their way through the crowded tunnel and dugout, passing Mick Jagger and Keith Richards. Bobby Vinton and Ed Sullivan joined the two Rolling Stones, among many others, on the bench usually occupied by Bobby Klaus and Ed Kranepool. Future Beatles business manager Allen Klein was there too, with the Stones.

Sullivan, who so famously introduced the Beatles to so much of America a year earlier, once again ushered the band to the stage: “Honored by their country, decorated by their queen, and loved here in America — here are the Beatles!”

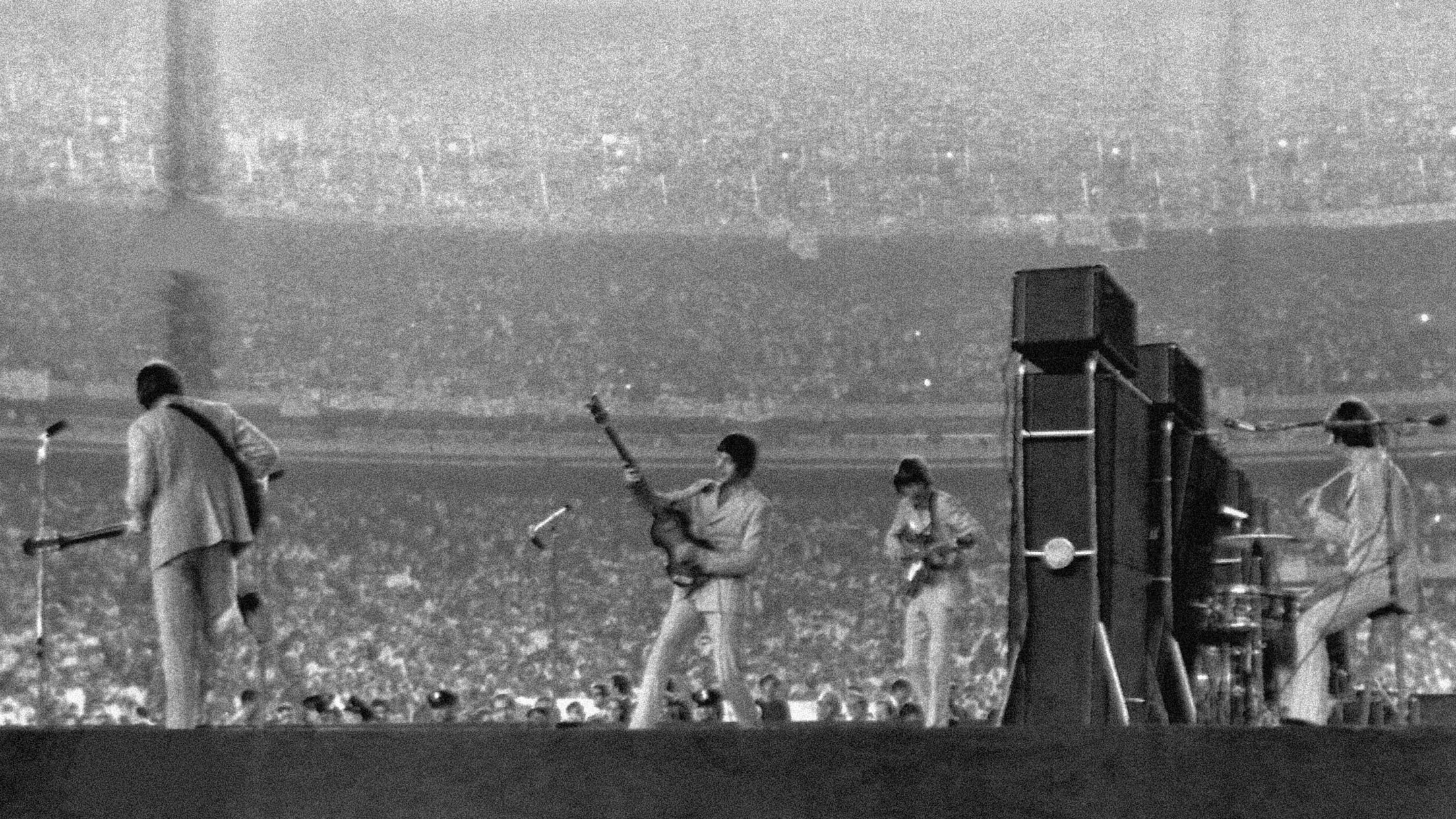

John, Paul, George and Ringo broke into a trot heading through the infield to the stage just after 9 p.m., instinctively waving to the crowd while clearly processing the scale of the event.

“I have never heard such an ear-splitting din as those kids kicked up when the Beatles made their entrance that night,” Evans wrote. “The whole place went absolutely crazy.”

Staged at second base, the group was very much on an island. There was no seating on the field – Bernstein asked, but the Mets quickly nixed the idea, citing the short turnaround to repair the grass before the team returned from their road trip five days later.

“What I remember most about the concert is that we were so far away from the audience,” Ringo said decades later in the Beatles Anthology. “It was just very distant at Shea.”

Without a backdrop, there was nothing but the entirety of the vast, empty outfield behind Ringo’s drum kit, and often the band would be distracted by fans scaling the walls and being intercepted by security.

This was despite a plea posted on the scoreboard: “FOR SAFETY SAKE, PLEASE STAY IN YOUR SEATS”

The Beatles were surrounded by spectacle: Full-throated screaming fans, at least the ones who weren’t weeping, fanned across the decks of the stadium, where dozens of banners hung from the rafters professed love for the Beatles. Fans seated behind home plate, hysterically yanked at the protective netting.

“Again and again police at the edge of the grandstand gently slapped the faces of long-haired little girls who were on the verge of collapsing from the ecstasy of it all,” UPI reported.

Jagger called the scene “frightening,” while Richards said it was “deafening.”

In their concert review published the next day, the New York Times painted a colorfully extreme picture of the audience.

“Their immature lungs produced a sound so staggering, so massive, so shrill and sustained that it quickly crossed the line from enthusiasm into hysteria and was soon in the area of the classic Greek meaning of the word pandemonium — the region of all demons.”

Decades later, Paul was much more kind, saying “the crowd noise was phenomenal — it sounded like a million seagulls.”

New VOX amplifiers, which were upgraded from 30 to 100 watts for this tour, sat on stage while an array of about two dozen columned speakers were lined up to approximate the baselines before curling into the outfield.

The Beatles perform from their second-base stage on Aug. 15, 1965. (Getty)

“Shea Stadium was an enormous place,” George said decades later in Anthology. “In those days, people were still playing the Astoria Cinema at Finsbury Park.”

That setup, aggressive for its time, was no match for the crowd noise, and hooking the audio into the stadium’s public address system — an effort to pipe the sound to as many corners of the ballpark as possible — didn’t do too much, either.

“I don’t think we were heard much by the audience,” Paul said. “The normal baseball-stadium PA was intended for: ‘Ladies and gentlemen, the next player is …’ But that was handy in that if we were a bit out of tune or didn’t play the right note, nobody noticed.”

The Beatles performed a standard 30-minute set — that’s about two innings of baseball in 2025. They completely tore through a dozen songs, with no let-up, no quiet moments.

From their first song, “Twist and Shout,” through their closer, “I’m Down,” and with recent No. 1 hits “I Feel Fine,” “Can’t Buy Me Love,” “Help!” “A Hard Days Night,” “Ticket to Ride” among those in between, it’s exhausting to list how powerful the Beatles’ concise set really was.

“It would have been better still if we could have heard what we were playing,” John said after the show. “I wasn’t sure what key I was in during two numbers.”

Pure energy was fed from fan to Fab on one of those nights that Shea shook, as those who ever experienced that phenomenon understands. The show’s performance was simply joy and wonder on stage. There weren’t any slow songs or moments of quiet reflection. The fans presumably were singing along (the ones who could hear anything), but none of the songs were a sing-a-long.

There were no video screens either, in 1965.

“They exaggerated every facial expression and bodily gesture in order to reach out to the crowd on the far side of this vast field,” wrote Beatles press officer Tony Barrow in his memoirs.

The Beatles used body language to communicate with each other, too.

“I could not hear anything,” Ringo recalled in the 2016 documentary Eight Days a Week. “I’d be watching John’s ass, Paul’s ass, his foot’s tapping, his head’s nodding to see where we were in the song.”

At multiple points John’s stage patter lapsed into gibberish — he knew no one in the crowd could understand him anyway, and he embraced the chaos. During “I’m Down,” John played the organ for the first time in concert. Feeling “naked without a guitar,” John simply entertained himself and his friends.

“I was putting my foot on it and George couldn’t play for laughing,” John said. “I was doing it for a laugh. The kids didn’t know what I was doing. … I was jumping about and I only played about two bars of it.”

Reflecting on the night, Ringo said John completely lost it in the moment. “I feel on that show John cracked up. He went mad, not mentally ill, but he just got crazy. He was playing the piano with his elbows and it was really strange.”

The most spectacular concert in American history!

New Musical Express, Aug. 20, 1965

With the euphoric conclusion to the concert, the Beatles left the stage, hopped in a white station wagon emblazoned with the Mets logo and with Shea groundskeeper Pete Flynn behind the wheel, and left the park via the center-field exit. Fans lingered at the stadium for more than an hour.

Newspaper reports published the next day tended to focus on two takeaways: Nobody heard anything, and the money the Beatles (and Bernstein) made.

The reaction to the performance was instantaneous. British music paper New Musical Express called it “[t]he most spectacular concert in American history!” in its Aug. 20, 1965, issue.

“Nobody could have foreseen the pandemonium unleashed as the four went through hit after hit,” the paper continued, “building the fevered excitement with each number.”

“It was marvelous,” John said after the show. “It was the biggest crowd we ever played. And it was fantastic.”

“Shea Stadium ’65 was in a class of its own,” Barrow wrote. “This was the ultimate pinnacle of Beatlemania.”

As fate would have it two future Beatles wives were in the crowd: Linda Eastman (Paul) and Barbara Bach (Ringo). (Yoko Ono has her own Shea ties, having participated in the 1974 Avant Garde Festival of New York, held at Shea).

The rest of the Beatles ’65 North American tour included additional big league destinations: two shows at Chicago’s Comiskey Park and one night at Metropolitan Stadium, home of the Twins. The Beatles also played Atlanta Stadium, where the Braves moved in a year later.

Bernstein brought the Beatles back to Shea in 1966, but it didn’t come close to a sellout. The Beatles weren’t quite the same, and neither was the industry, which was changing thanks in large part to the Beatles themselves. Still, Shea was how the members of the Beatles would define themselves.

The Beatles were back at Shea on Aug. 23, 1966, but sold 11,000 fewer tickets than a year earlier. (AP)

George, looking to establish himself as a solo artist in the wake of the Beatles’ breakup, said in 1970, “If I wanted to hear screaming, I would play Shea Stadium.”

“Shea Stadium was a happening,” John said in 1971. “You couldn’t hear any music at all. And that got boring. That’s why we stopped, really.”

Paul said as much, decades later in 2016. “Playing to 56,000 people at Shea Stadium, after that you just sort of think to yourself, ‘What more can you do?”

But there was more others could do, and that was use Shea as a measuring stick.

“One of the most remarkable aspects of the Beatles’ Shea Stadium concert was that it ushered in a new sense of scale,” Kenneth Womack, professor of English and Popular Music at Monmouth University and author of several books about the Beatles, told MLB.com. “Quite suddenly, arenas were no longer the be-all and end-all for touring musicians.

“Selling out venues like Shea, which required turning out vast numbers of fans for a single show, upped the ante when it came to superstardom. In many ways, the Beatles’ 1965 Shea Stadium gig was a harbinger of even larger things to come when it came to big time, commercial rock ’n’ roll. Think Led Zeppelin and other assorted acts in the 1970s.”

The Beatles’ 1965 performance at Shea became the laboratory that would establish the limitations of the large-scale concert, while heralding that new era. The crowd was too far and couldn’t hear anything, and neither could the band. But this could be fixed imminently in the next generation.

And Shea itself became aspirational for major touring acts. The Rolling Stones, the Who, the Police, the Clash, Simon & Garfunkel, Guns ‘N Roses, Bruce Springsteen, Billy Joel — the list of historic acts to follow the Beatles’ pioneering footsteps with concerts at Shea is even longer than that.

“I’m English. I know nothing about baseball,” Sting said. “So Shea Stadium was never this baseball legend at all. It was where the Beatles played.”

When the Police played Shea in ’83, Sting thanked the Beatles from onstage “for lending us their stadium.” Years later he recalled the night, saying, “You can’t get better than this. You can’t climb a higher mountain than this. This is Everest.”

Seats from Shea Stadium (albeit from a later generation) are museum pieces across the globe at the Liverpool Beatles Museum. (Dan Rivkin)

By the time the ’65 concert film — which featured some highly overdubbed audio as rerecorded by the Beatles in January 1966 — aired on TV to American audiences in January 1967, the Beatles had already retired from touring, calling it quits after performing at the Giants’ home, Candlestick Park. By October 1969, the Beatles ceased recording as a unit, while Shea Stadium, the home of the worst team in baseball for much of the 1960s, hosted a World Series champion. A lot can change in a little time.

“I know that the Pope was there, and President Clinton was there the night that they honored Jackie Robinson on the 40th anniversary of his debut,” Rose said. “And you know there have been other big non-baseball moments at that ballpark. But the Beatles were a moment all unto themselves.

“The Beatles transcend baseball for me. So what happened at Shea Stadium in the Summer of ’65 and ’66 was historic in a way that baseball isn’t, because the Beatles were more global than baseball, or certainly the Mets, as much as I love it and them.”

Billy Joel dropped the curtain on Shea Stadium as a live music venue, staging a pair of concerts in mid-July 2008. Paul McCartney was inevitably the final of a string of special guests during the two-night stand, arriving at the end of the second show just in time, with a little help from air traffic control and a police escort. Flynn was back at the wheel in ‘08, this time chauffeuring Paul in much less frantic fashion via golf cart.

Paul hadn’t yet written “Let It Be” when the Beatles played at Shea; it was the final song performed at the ballpark, when Joel deferred and handed over the mic and piano to his predecessor. This time Paul was performing on a state-of-the-art sound system, deep in center field, with fans seated on the field of an outdated ballpark.

But that wasn’t the last time a Beatles song echoed through Shea.

After a bitter loss to the Marlins on Sept. 28, 2008, that marked the last day the ballpark opened its doors, Howie Rose acted as master of ceremonies once again as the Mets welcomed franchise greats spanning their history for one last ovation from the crowd of more than 56,000.

Tom Seaver threw a final pitch to Hall of Fame batterymate Mike Piazza, and they walked off to the center-field exit as the Beatles’ “In My Life” played through the stadium PA for anyone who could hear above the din of the capacity crowd.

Dan Rivkin is director of content operations for MLB.com and writes about the Beatles at They May Be Parted.