A structured unfolding

Since its earliest days, often wrapped in myth and silence, chess has accompanied humanity not only as a game, but as a reflection of itself. In every square and every move, there is more than strategy: there is a story, a symbol, a question. This ancient game, with its geometric clarity, strict rules and opposing colours, has become a small world in which the tensions that define us reappear: order and chaos, light and shadow, matter and spirit, freedom and destiny.

It is not surprising that civilizations as varied as the Chinese, Indian, Persian, Arabic and medieval European cultures saw in chess a metaphor for the cosmos. At its core, that is what it suggests: a quiet image of a universe in motion. The board, with its sixty-four squares, evokes completeness, the structure of time and the balance of forces that shape life. Like a silent mandala, it invites reflection from the stillness of a single square.

And when two armies – one white, one black – stand opposite each other, it is more than a contest between players. It becomes an encounter of complementary principles, a structured unfolding. Neither side holds moral superiority: both have the same power, the same potential. As in life, the meaning lies less in the final victory than in how tension is managed and how balance is maintained within conflict.

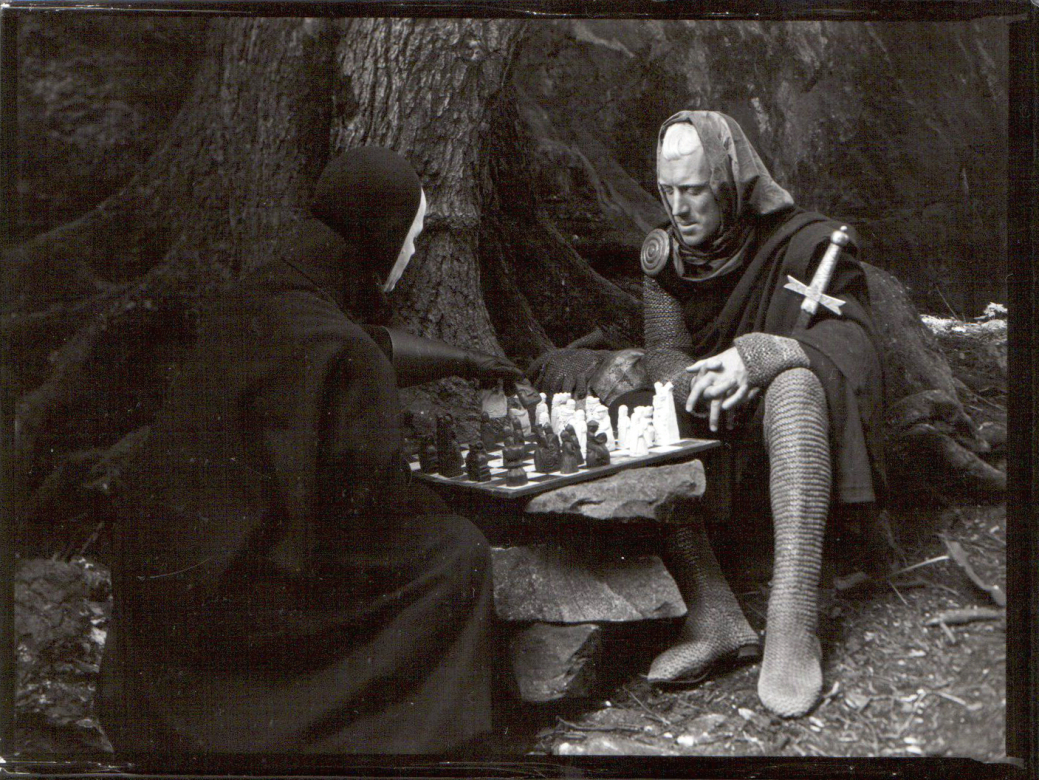

Antonius (Max von Sydow) meets Death (Bengt Ekerot) at the chessboard in Ingmar Bergman’s “Seventh Seal” | Photo: Louis Huch © AB Svensk Filmindustri

Each piece carries a distinct character, a different way of acting in the world. The rook suggests stability; the bishop, indirect vision; the knight, the unexpected move that breaks patterns to create new routes. The queen holds the widest range of motion; the king, though limited, remains the vulnerable centre that sustains the game. When these pieces move, they do more than change position: they interact, they represent ideas. They are like notes within a larger composition.

Every match can be seen as a brief account of a larger order. The opening signals the beginning of action; the middlegame brings confrontation; the endgame offers resolution, whether decisive or restrained. When strong minds meet over the board, what appears is not only calculation, but also creativity, thought and a form of art in motion.

Earlier thinkers sensed this dimension. In India, Chaturanga symbolized balance; among Sufi thinkers, the board became a path inward: the aim was not only to defeat an opponent, but to understand oneself. Each move marked a step in that process.

Although modern times have framed chess as a sport and a logical discipline, its deeper quality has remained. The nineteenth century, especially among the so-called romantics of the board, treated it as creative expression. Anderssen, Morphy and Steinitz approached the game with a sense of invention. In the twentieth century, writers such as Zweig and Nabokov recognized in chess a metaphor for inner conflict and the intensity of thought.

Ingmar Bergman was inspired by a medieval painting in the ceiling of the church of Täby, painted by Albertus Pictor – the painting depicts a knight playing chess with Death.

Even contemporary science has drawn parallels. Chess, with simple rules and vast possibilities, resembles complex physical systems. Each move changes the position, as a small shift can alter an entire field. A single inaccuracy can reshape the outcome. Much like life.

Yet perhaps the most lasting aspect of chess is not its ability to mirror the universe, but its quiet lessons about living in it. The board does not command: it presents choices. It encourages foresight, responsibility and respect for limits. It shows that winning is not merely overpowering, but understanding, that balance brings clarity – and meaning grows from careful attention to each move.

In a world where certainty often feels fragile and disorder seems close at hand, this old game offers orientation. Not a rigid system, but a reminder that meaning can be found amid complexity. That even on a simple wooden board, essential questions can surface again.

In the end, every pawn holds potential. And every move is a way of searching – quietly – for a sense of balance.

References

- Aldegani, E., & Almeida, L. G. (2023). Ejército, juego y orden social: una aproximación a la metáfora cósmica de la justificación de la guerra en De bello de Juan de Legnano. Mirabilia: Electronic Journal of Antiquity, Middle & Modern Ages, (37), 7.

- Blanco-Hernández, U. (2025). Ajedrez y filosofía: el tablero como arquetipo del mundo interior. Editorial Jaque Mate, Mexico.

- Blanco-Hernández, U. J. (2021). ¿Por qué el ajedrez debe ser reconocido como Patrimonio Cultural Intangible de la Humanidad? Capablanca, 2(3).

- Cazaux, J.-L., & Knowlton, R. (2017). A World of Chess: Its Development and Variations through Centuries and Civilizations. McFarland.

- Eales, R. (2002). Chess: The History of a Game. Batsford.

- Frolow, A. (1981). Le jeu d’échecs: Figures et significations. Droz.

- Jung, C. G. (1995). El hombre y sus símbolos. Paidós.

- Kasparov, G. (2007). How Life Imitates Chess: Making the Right Moves—from the Board to the Boardroom. Bloomsbury.

- Murray, H. J. R. (1962). A History of Chess. Oxford University Press.

- Ortega, C. F. V. (2024). Lezama Lima y el ajedrez. Letras, 1(75), 65-80.

- Pieper, J. (1999). Sobre el ocio y la vida contemplativa. Rialp.

- Tinajero, R. (2017). Fábulas e historias de estrategas. Fondo de Cultura Económica.