Forty years later, there‘s still no one like Richie Evans.

Nine NASCAR Modified championships. Winner of the inaugural Whelen Modified Tour title and an estimated 475 races. NASCAR Hall of Famer.

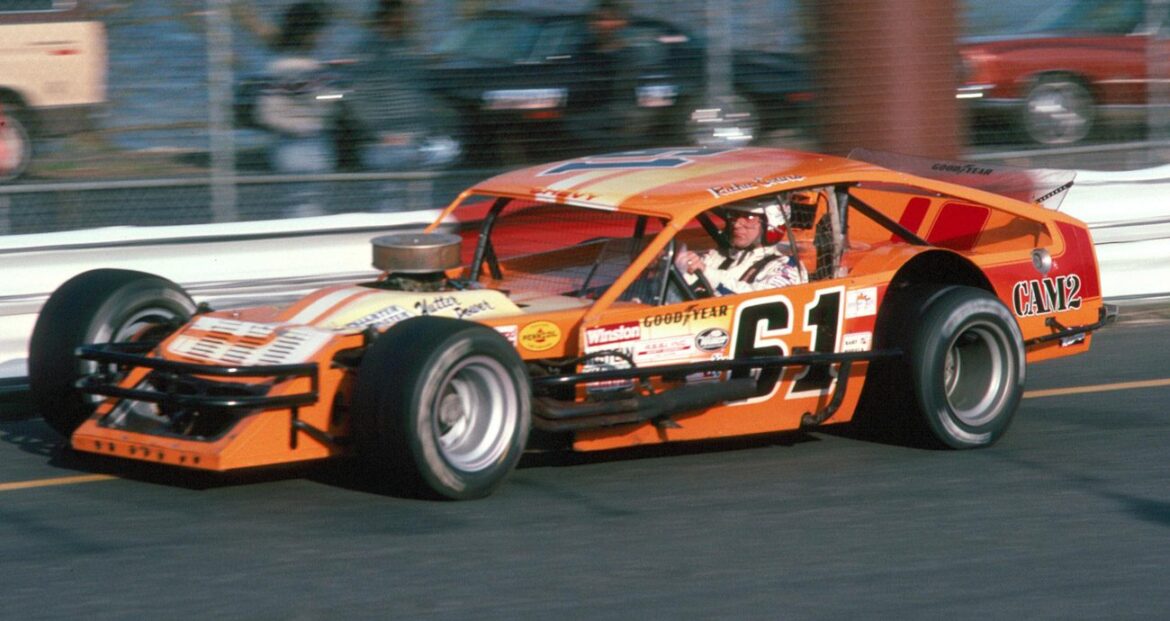

The only man in NASCAR to have his number — the iconic No. 61 — retired from his respective division.

RELATED: More Modified coverage

Those professional milestones define part of his story but not all of it. The other is defined by his character: A friendly, helpful, driven and confident-yet-gregarious face from Central New York who was always ready for a post-race party.

On Oct. 24, 1985, Evans died driving a Modified stock car around Martinsville Speedway in Virginia, practicing for the finale of the inaugural Modified Tour season. His legacy lives on four decades later. And while there was no one like him, it‘s hard for longtime industry voices to avoid drawing obvious parallels to another NASCAR Hall of Fame icon: seven-time Cup Series champion Dale Earnhardt.

Mike Joy, FOX Sports‘ lead NASCAR announcer, was on the call when Earnhardt was killed in a last-lap crash at the 2001 Daytona 500. He also was at Martinsville Speedway on the day Evans died (set to broadcast what should have been Evans‘ championship coronation for the Motor Racing Network). A Northeast native who grew up in Modified country, Joy said Evans‘ death “was bigger to Modified racing than Dale Earnhardt’s death was to Cup racing.”

“Certainly there was the same sense of, ‘Well, if it can happen to Richie, it can happen to any of us,‘ ” Joy said.

Said Tommy Baldwin Jr., who grew up the son of another Modified legend in New York before winning a Daytona 500 as a crew chief and becoming the competition director for Rick Ware Racing: “Simplest way to put it is, (Evans) was the Dale Earnhardt of the Northeast.”

A New Jersey native who grew up immersed in Modified Racing before he became a NASCAR Hall of Fame crew chief for Jeff Gordon, Ray Evernham sees striking similarities between the influence of Earnhardt and Evans.

“The day that Dale Earnhardt died,” Evernham said, “I told people, NASCAR racing is never going to be the same. Cup is never going to be the same. And the day that Richie died, I said same thing. And it’s just not.

“Neither one of those memories or neither one of those sports were ever the same for me.”

RELATED: Modified schedule at Martinsville

And yet 40 years later, the image of Evans‘ bright orange No. 61 stands prominently — fondly — in the minds of those who were fortunate enough to see it sit in Victory Lane. The hope, of course, is that fans of today remember it for another 40 at least.

“The younger people that didn’t get a chance to meet Rich really need to know,” Evernham said. “You need to know what his legacy is.”

That legacy will be remembered this weekend at Martinsville Speedway. Thursday‘s Modified race at the famous short track will be held a day before the 40-year anniversary of Evans‘ death, which still reverberates decades later.

ECHOES IN ROME

In Rome, New York, some 45 minutes northeast of Syracuse, Richie Evans‘ race shop is still operational 40 years after his death. The concrete and stone building is gray and weathered, but the spirit of racing radiates from the garage on Calvert Street.

Inside the building are three men and two Modifieds, which both carry the same color schemes as when Evans‘ distinctively orange cars left the building.

As a 15-year-old in 1973, Billy “Bondo” Clark began painting those cars for Evans, using a “Department of Transportation” orange that he first hustled from the city‘s garage before he began purchasing it from the now-shuttered Mangino Auto Supply.

“It was the same number — 1021,” Clark said. “And it‘s actually more of a yellow than it is an orange, but it turns orange after it ages a bit.”

At 67, he‘s still painting cars out of the same shop, now for Tony Pettinelli as they prepare the No. 2 NY Modified for another race at the nearby Evan Mills Raceway Park.

Evans‘ first garage was up the street from its current location, right on the corner where Pettinelli and friends once congregated just to admire Evans‘ coupes and get stickers for their bicycles. Eventually, Pettinelli lingered around long enough to earn a job. And as much as Evans‘ reputation for having fun looms large, he also could be a taskmaster.

“The No. 1 goal was the orange car came first,” Pettinelli said. “That’s it. We won as a team. We lost as a team. We worked as a team. There was no I. Believe me, that guy wrote the book on that. There is no I ever. And you listen to any of his interviews, it was, ‘We did this, we did that. We won the race. We suck. We whatever.‘ We never said, ‘I did this,‘ unless you were taking responsibility for something.”

Evans made sure his team knew it was a joint effort from start to finish. From Pettinelli to Clark to crew chief Billy Nacewicz and Ray Spognardi, there were always plenty of hands on deck to help prep that iconic No. 61.

“There‘s no man working in my garage an hour that I‘m not there working with him,” Evans said in a radio interview. “I think that makes the guys work better, and I don‘t just pop in the garage and say, ‘Hey, why the heck didn‘t you do this or that?‘ And I think they feel like if I‘m that committed, they should be that committed, and I think it makes everything work better.”

In Evans‘ heyday, the front room of the shop was filled with tires left and right, thanks first to a Firestone deal and later one with Goodyear, Pettinelli said. As strong a mechanic as Evans was, his knowledge of how the tires would react was even stronger.

“He could tell you what that tire was going to do before it did it,” Pettinelli said. “I don’t know what it was, how he saw them, after you scuffed them in, whatever — he just had an unbelievable knowledge of tires.”

But there was also an uncanny awareness that Evans carried with him around the track.

“He’d tell you something that went on half a lap behind him, and he’d tell you what the guy did,” Pettinelli laughed. “We’d look at each other and play the ‘The Twilight Zone‘ (theme). Used to do that all the time.”

Tires and awareness were key, but so, too, was setting up the car for success. Evans was masterful with a wrench and knew what he needed to feel in order to lead when the pay window opened.

“He was a genius mechanic,” Clark said. “He just had a feel for stuff. He had an ear for (it). He knew why stuff worked the way it did. He grew up on a farm where they didn’t have a lot of money and you had to fix stuff. He was good at that. He was gifted.”

A FATEFUL PLACE AND TIME

Martinsville Speedway also was the site of Evans‘ defining win.

Geoff Bodine had won the late model race before the Dogwood 500 Modified feature began on March 15, 1981. The Modified race began just as well for Bodine, who led a dominant 231 of 250 laps. But coming down to the wire with only four cars on the lead lap, Evans hounded him for the lead in the closing moments.

Baldwin was a spectator that day, watching with his father as the orange No. 61 knocked Bodine‘s white No. 99 out of the groove. “I think the wreck at Martinville with Geoff and Rich is probably the most iconic, incredible finish that you can ever have,” Baldwin said.

Evans and Bodine collided on corner exit with Bodine pinched into the outside wall as Evans leaned against him. Bodine‘s left front caught Evans‘ right rear, sending the No. 61 into the wall and climbing the catchfence while the car tipped on its left side. Parts and pieces blew apart, but Evans never lifted and took home the trophy by leading only the final lap.

“We looked at each other down into the corner,” Bodine recalled to NASCAR.com. “I was at the finish line. We looked at each other. Everyone knew we were gonna go fight each other, but we just looked at each other, kind of shook our heads and went about business. It was racing.”

Jerry Cook, himself a six-time national modified champion from Rome, New York, was riding behind and hoping Evans and Bodine would wreck before the checkered flag. He got his wish — but was foiled as their destroyed race cars still were scored ahead of his. “They were both junk,” Cook said, “but they made it over the finish line.”

The moment was the greatest of Evans‘ 10 victories at Martinsville, but they would be joylessly overshadowed by his Turn 3 crash during practice on Oct. 24, 1985.

There‘s a natural pause each person takes when recalling the day Evans lost his life.

He had already clinched the inaugural NASCAR Whelen Modified Tour championship for 1985 after placing sixth in the season‘s 28th and penultimate race at Thompson Speedway. It was a successful year across the board for Evans, who netted 12 wins.

Pettinelli was invited by Evans to tag along to the Martinsville season finale, Though he attended most weekends, Pettinelli turned down the trip to stay home and focus on his job and young family. “I said, ‘Well, I can’t go,‘ ” Pettinelli said. “I’m glad I didn’t.”

What exactly happened in the crash remains unknown.

Some racers speculated a stuck throttle sent Evans‘ car into the concrete wall between Turns 3 and 4. Others close to Evans speculate that he was suffering a medical emergency before the impact.

No matter what happened to trigger the accident, a racing legend was lost in a flash.

“We have no idea at all why,” a track spokesman told the Associated Press after the crash. “It was just a straight practice session, and the car just hit the wall. No other cars were near him.”

Having spent his childhood racing at tracks all over the East Coast with his father, Baldwin Jr. was at Martinsville that fateful day and recalls running to Evans‘ team with saws and tools to extricate him.

“That was a bad day,” Baldwin said. “We actually had a conversation with him right before the practice. Yeah, just a sucky day, man. We lost a legend.”

Evans won eight consecutive national championships. He was revered from the Modified ranks to the Cup ranks, where he made his strongest impressions on the high banks of Daytona International Speedway and bested drivers like Darrell Waltrip and Bobby Allison in exhibition races. In many respects, all he did was win.

The Modified Tour‘s inaugural 1985 season was a good example. He won 12 of 28 starts with 17 top fives and 21 top 10s.

And in one corner, Evans was gone.

Left to handle the fallout were Clark, Nacewicz and Co. Once the car was returned to the team, Clark hauled it back to Syracuse and met Evans‘ wife, Lynn, at the airport as she returned with Evans‘ body.

“We met the hearse there, and we followed that back to Rome,” Clark said. “And when I pulled in on the street here, there were cars parked for two blocks in either direction. The place was mobbed. It was a crazy, crazy time.”

Services for Evans were held in Rome at the Capitol Theatre and drew an overflow crowd that included Richard Petty and Bill France Jr. Clark recalls the motorcade to Westernville Cemetery stretching for 10 miles.

Evans‘ final race car was cut to pieces by Nacewicz and Clark one night in the privacy of their shop.

“There wasn’t too many parts on the car that were actually savable,” Clark said. “It was crushed pretty good. The cage never moved, but he had a fiberglass seat, an open helmet. They didn’t have the HANS devices back then. None of that stuff. Whether that would have made a difference or not, can’t say.”

What changed as a result of Evans‘ death was improving the safety of NASCAR‘s Modifieds, much as how the Cup Series became safer after Earnhardt‘s death in 2001.

After retiring from racing in 1982, Cook went to work for NASCAR and was the inaugural director of the Whelen Modified Tour when Evans crashed at Martinsville. He worked with top NASCAR officials such as Gary Nelson and John Darby on enhancements to the Modified cars, which had too many short pieces of straight tubing.

“We’re very fortunate that with the changes made to the cars, the opportunity for fatalities in the Modifieds decreased,” Joy said. “We just know much more than we did. It’s just a sea change in safety that’s come since all of this happened.”

TOP OF THE BLUE COLLAR GUYS

With a population of roughly 32,000, Rome, New York, is far from the biggest town in the country (let alone state). Yet the town has produced a modest but notable share of professional sports figures: Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred; former ballplayer Archi Cianfrocco; and two NASCAR Hall of Famers in Evans and Cook.

Their histories, along with others, are commemorated in the Rome Sports Hall of Fame, a humble building that sits in front of what was once home to a bustling market at Erie Canal Village. Inside the single-story museum are the monstrous, mean machines Cook and Evans used to race — Cook‘s glowing red No. 38 and Evans‘ dazzling orange No. 61. Their stories are told through sprawling scrapbooks and the myriad plaques and photos covering the walls.

Prevalent in each piece of memorabilia is Evans‘ signature grin. For as easy as Evans made racing look, he was just as easily approached. Anyone who had a question for him was met with sincere advice, whether about driving, suspension parts or tires.

“What was so cool about it is everybody was his friend at the end of the night,” Baldwin Jr. said. “If you wanted to go hang out and have a beer and hang out and talk and shoot the [expletive] and ask questions, he was there.”

Long before he became a mechanic in IROC and then a renowned crew chief and team owner in NASCAR, Evernham said Evans “was always, always, very, very nice to me.

“He was, to me, the top of the blue-collar Modified guys,” Evernham said. “Worked hard, raced for a living, had a beer. And whether you were another championship-caliber racer or just some kid like me, he’d have a beer with you.”

From his home track at Utica Rome Speedway to Stafford Springs in Connecticut and to Daytona International Speedway, Evans was the man to beat. Just ask Cook.

Their home garages were separated by just 3 miles and a couple turns off Thomas Street. For 15 years, the Modified championship stayed in Rome — nine times with Evans, six with Cook. While their rivalry was more friend than foe, the competitive nature between the two knew no bounds.

Before the NASCAR Whelen Modified Tour was formed in 1985, the national championship was determined by points scored in races across the country. Run more races? Earn more points. Win more races? Earn even more points.

That meant tracking — and tricking — your closest competition. Where‘s Richie running? Where‘s Jerry running? Well, that was up for debate at times because they would send decoy trailers down the highway to disguise which track they were racing.

“What I tell people all the time now is all them stories you heard about me and Richie, they’re all true — and then some,” Cook told NASCAR.com with a laugh.

Regardless of the subterfuge, Evans still was always willing to lend a helping hand.

Setup advice? Sure. Stickers for your bike? You bet. Tire secrets? Don‘t mention it.

It was that sort of grace that defined Evans‘ character.

“That was kind of selfish on his part in a way, because when he came up on that guy (in a race), he knew that guy wasn‘t going to be in the way,” Pettinelli said. “So selfish on his part, but it was also generous.”

Therein lies the importance of remembering one of stock-car racing‘s greatest representatives. The trophies, the success, the wins were all critical in establishing Evans‘ excellence. But how he treated people off the track is what helped grow the sport, creating more passionate fans, better race car drivers and more thrilling shows.

Joy recalled how Evans put a young Mike Stefanik in his backup car (changing the number from 61 to 16) at Thompson Speedway, launching another NASCAR Hall of Fame career.

“Richie had that kind of influence in the sport and on people,” Joy said. “If Richie said you had talent, man, everybody sat up and paid attention. He was the straw that stirred the drink.”

Until that dark day at Martinsville.

“Just like the song goes, the day the music died, that was it,” Pettinelli said. “That was Modified racing. You can kind of compare it to Cup racing with Earnhardt. The two greatest stars of your sport in their respective areas. Just tough to recover from that.”