“Where are we at, Nic?” I ask the guy riding next to me, whose head is nodding like a dashboard dog. While staying alert to the London traffic around him, he is continually glancing down at his bar-mounted screen.

We’re by Westminster Bridge, I know that much – I was a bike courier in the Big Smoke for a while – but I’m not enquiring about our geographical whereabouts. I want to know where we are in the picture we’re drawing while we’re pedalling.

“Right in the palm of the hand,” comes the reply as we grind to a halt, prompting a quizzical glance from a commuter beside us. The lights change, and we’re off before I have a chance to explain – not that I’d know where to begin. I’m cycling with Nicolas Georgiou, a pedal-powered creator of some renown – at least in the admittedly niche world of Strava art.

Still, Georgiou has a following of thousands across his social media accounts, plus a coveted ‘Verified Athlete’ tick on Strava. He has received accolades from around the globe for his work, which involves creating images on a map, and then cycling them into (virtual) existence. He’s essentially a conceptual artist, using the streets of London as his canvas and his Specialized Roval Rapide wheels in lieu of a brush.

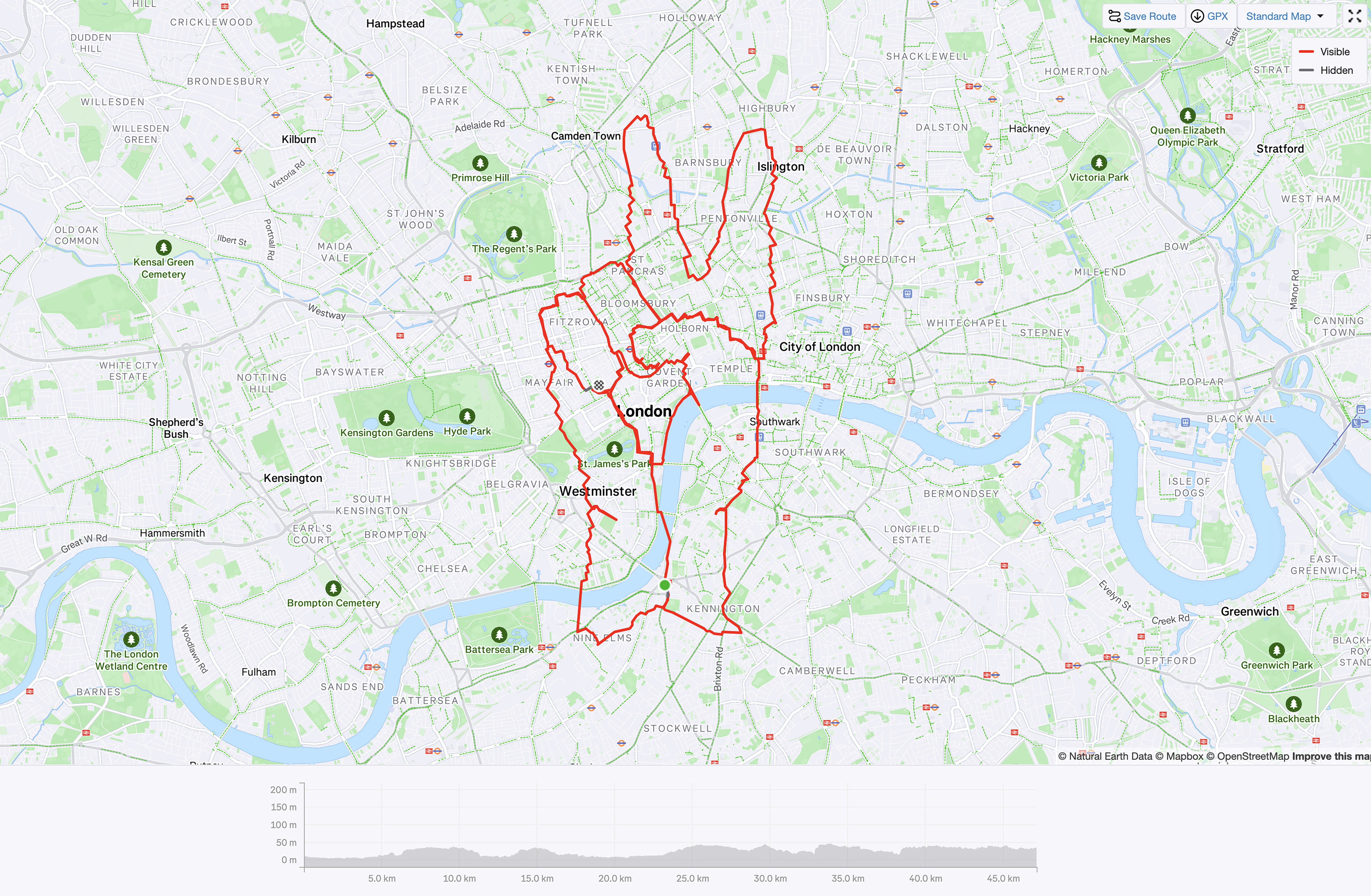

It’s July, and today we are riding Georgiou’s latest creation: a huge hand, cloaked in a cycling glove, making the peace sign. I understand our objective, but it’s hard to picture the details from ground level, and I’ve lost all sense of where we are in the artwork. The early evening rush hour has begun, and we’ve been stop-start cycling since 7am.

I’m starting to wonder what I’ve got myself into. “Don’t worry,” Georgiou reassures me. “When you download the file, it will all feel worthwhile.” We begin to cross Waterloo Bridge, but he turns us around halfway across the river and we return to the north bank – to finish off the thumb, apparently.

The graveyard slot

Like most Strava users, I occasionally upload a ride and notice that the shape of the route I’ve ridden resembles something, that I’ve inadvertently drawn a picture – usually crude, sometimes rude.

Strava art may have begun with such schoolboy-level musings, but it is now something far more sophisticated. Georgiou is a clothes designer by profession, and his attention to detail and fondness for flair shines through in his Strava art.

He began in earnest three years ago, after crashing his bike and breaking a shoulder and three ribs. Stuck inside for six weeks, using Zwift and staring at screens, he plotted a 100-mile cycling route shaped like a tiger, leaping between Catford and Notting Hill, to mark the Chinese New Year. As soon as he was fit enough, he went and rode it – and caught the bug.

When we pause for a caffeine pit-stop, Georgiou goes through a gallery of photos from his portfolio of Strava art. “Here I am at 3.30am on Halloween morning, wearing a skeleton suit, in a graveyard, in the pissing rain,” he says, laughing. “What’s wrong with me?” It’s a valid question, considering that long, lonely ride – sketching a skull while visiting London’s seven Victorian cemeteries – took him 23 hours.

“GEORGIOU HAS AN ONLINE FOLLOWING OF THOUSANDS”

Using locations and themes, Georgiou instils all his creations with meaning and nuance, and consequently they grab people’s attention, as art should.

Our ‘War and Peace’ ride began at the Imperial War Museum and we’re visiting the Peace Memorial Fountain by Smithfield Market and the Cenotaph in Whitehall en route.

Georgiou recently rode a Pugsy-the-Bear-shaped route to raise money for Children in Need, and to celebrate the Paris Olympics in 2024, he drew a gigantic discus-throwing athlete in front of the Olympic rings, a Herculean effort that involved riding over 260 miles and took 33 hours, leaving him with injured wrists.

Its epic masterpieces like these that saw him anointed as ‘Strava Artist of the Year’ by GCN. His work is truly exceptional, but he is far from alone in the field.

Tracing the origins

A Canadian cyclist named Stephen Lund pioneered the art form in 2015, with eye-catching creations on Vancouver Island that inspired others to give Strava art a try.

“THE IMAGE OF A GLOVED HAND TAKES SHAPE… IT FEELS ACE”

One of them was Anthony Hoyte, a Cheltenham-based cyclist who has travelled widely to complete designs in cities including London, Cardiff, Birmingham, Leeds, Nottingham, Sheffield, Manchester, Paris and Milan.

“I spend a lot of time looking at maps and aerial photographs, finding roads that look like something, a nose or an eye,” Hoyte explains. “I start there, and try to find the rest. Sometimes, I start with the theme, which is much more challenging. British roads lend themselves best to organic shapes, which is why my drawings are mostly animals and faces. I’m also a great believer in sticking to the roads.

Lots of Strava artists use the ‘stop-start’ method, whereby they create straight lines by pausing the recording, moving to a new point and unpausing it, allowing them to cycle ‘through’ buildings and so on. There are no rules in Strava art, but that’s not my style.”

MAPPING THE MASTERPIECE

All the creativity and most of the hard work behind a piece of Strava art happen before any pedals are pushed. Nicolas Georgiou spends months planning routes, poring over Google Maps, Komoot and Strava. Janine Strong simply uses Strava and an iPhone, while Anthony Hoyte employs an app called Scribble Maps before transferring the route into a mapping app (Ride with GPS) and creating a GPX file before uploading it to his Wahoo Elemnt Bolt.

Peter Stokes works for National Parks in Australia and has access to a Geographic Information System (GIS), through which he creates a KML file to use alongside Google Maps when navigating the route on his phone.

Road layouts play a big part in determining whether a picture is possible. Like most old cities, London is an incredibly complex maze of thoroughfares, and during our drawing day, Georgiou directs me along myriad mysterious alleyways and through hidden gates. These sneaky backstreets and cut-throughs – all publicly accessible (even if you sometimes have to dismount) – allow him to add intricate detail to his creations but require hours of painstaking research on Google Maps.

When you’re working with such an ancient, textured canvas, it helps to go big with the picture, he explains, because then imperfections are erased by scale and perspective. Zoom out and the full glory of the image is revealed.

“GEORGIOU DIRECTS ME ALONG MYSTERIOUS ALLEYWAYS AND THROUGH HIDDEN GATES”

Newer metropolises are typically built on grid systems, which present different opportunities and challenges. Janine Strong makes Strava art in cities in Canada and the US. “When I first started, I’d spend hours looking at the angles of the streets and the shapes they made to see what they suggested,” she explains.

“My ‘Girl with a Pearl Earring’ piece came from noticing the long parallel streets in Brooklyn that form her headdress. The ‘Crocodile’ in Vancouver was inspired by the road that outlines the snout. ‘Santa Claus’ in Victoria started with the ring road that makes up the pompom of his hat.”

Strong might be working with more straight lines than her European counterparts, but her pieces also have plenty of depth.

“I especially enjoy it when a drawing connects to the place itself,” she says. “The most recent piece I did in New Mexico depicted a cob of corn, which was inspired by the kernellike street grid in Downtown and Old Town Albuquerque. Corn carries deep cultural and spiritual significance there, so it felt like the perfect fit. The longest drawing I’ve done was a vine along the entire length of Cape Cod. It took me three days, over almost 300 miles.”

Multi-discipline art

Of course, Strava art can be created by runners and walkers, as well as cyclists. Switzerland-based multisport athlete and artist Jean-Sébastien Weiss uses a mixture of riding and running to create his compositions, often alternating between bike and foot to achieve one image.

He’s even been seen plotting pictures using wild swimming routes. Heading off-road arguably makes it easier for artists plotting by foot, who can use open terrain to draw whatever they like, completely unconstrained by bridleways and streets.

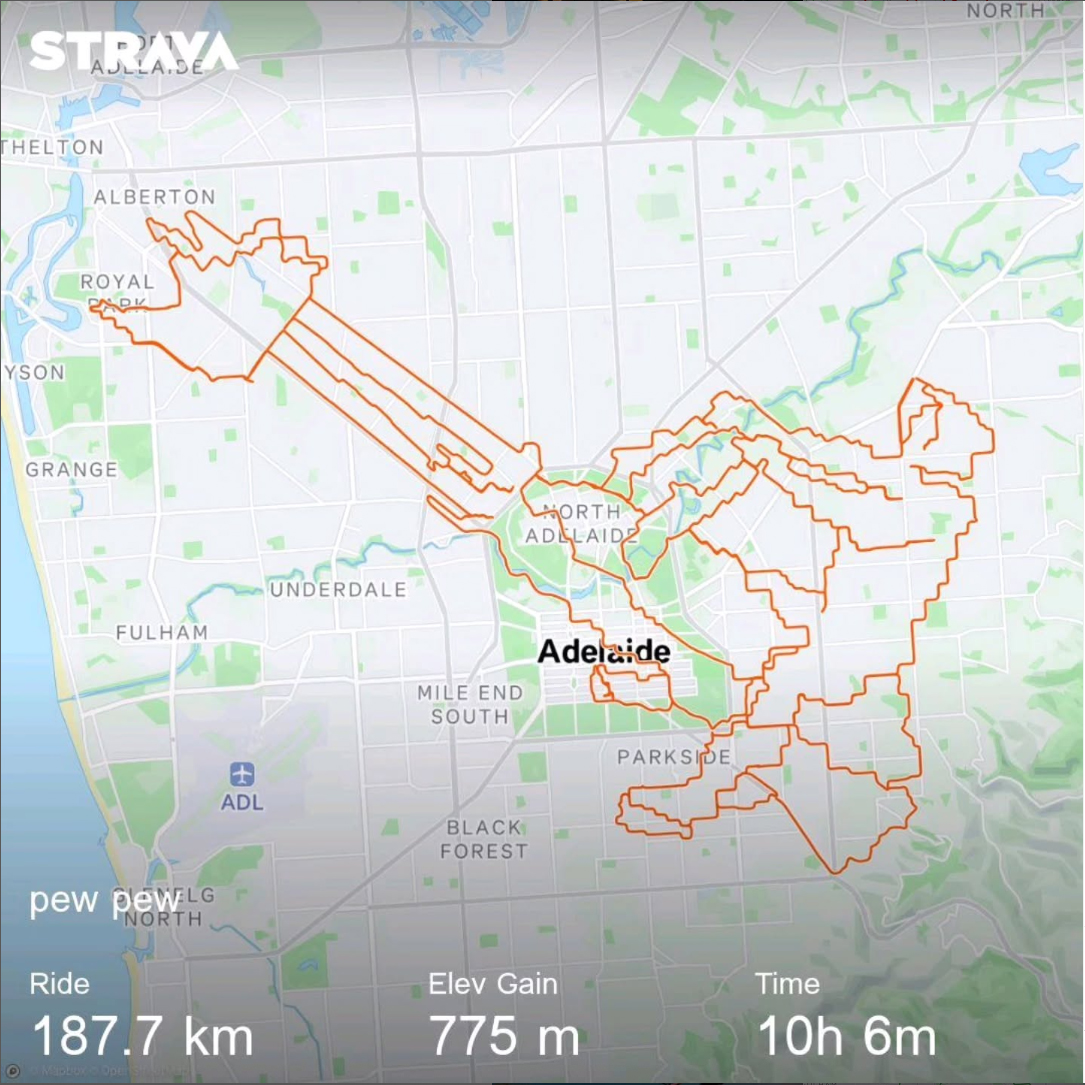

Australian artist Stokes, who lives in Adelaide – a National Park City, like London – has adopted this freestyle approach to his bike-based work. “While I’m a mountain biker in my leisure time, I use my regular commuter bike for my Strava art rides,” he tells me.

“It’s a single-speed Trek Crockett cyclocross bike, running 42mm semi-slick tyres – good enough for doing big kilometres, but also tough enough if I need to bomb down a loose rocky trail to make the route work. And it’s pretty light, so easy to lift over the occasional fence.”

Though he prefers working alone, Stokes occasionally makes an exception. “Years ago, I took a group riding to raise awareness for a koala care centre,” he recounts. “It was Tour Down Under time, and we roped in Phil Liggett to join us. As we were approaching a T-junction, slowing down to wait for passing traffic, Phil just shot past me onto the road crossing.

“He made it across just fine – obviously, because the world would have heard about losing its favourite cycling commentator to a koala – but my heart was in my mouth.”

Conscious of how frustrating the stop-start process can feel, Georgiou repeatedly apologises as he leads me around seemingly endless backstreets.

Several times we’re almost thwarted by roadworks and street closures, but finally, after venturing north to Camden and Islington to draw the V-shaped fingers, we loop back through Piccadilly Circus and Soho to finish at the Rapha clubhouse on Brewer Street, just in time to watch on TV Valentin Paret-Peintre edge out Ben Healy for a TdF stage win on Mont Ventoux.

As we sit down for coffee and cake, it’s moment-of-truth time. Devices stopped, we hit save and our ride begins to upload. The pessimist in me braces for a jumbled mess, but instead something magical happens – the clear image of a gloved hand making the peace sign takes shape across a map of London. Georgiou is right; it feels ace. Maybe it’s the donut sugar rush after eight hours in the saddle, but I’m buzzing.

In my mind, I’m making links to famous, grand-scale works of art: the enigmatic Nazca Lines in southern Peru and the giant, club-wielding figure on the chalky hillside at Cerne Abbas. Unlike those geoglyphs, Strava art leaves no trace on the ground but endures online, often piquing the interest of people all over the world – as Georgiou’s pinging phone attests. I don’t have the skill or patience to create my own Strava artworks, but I now fully appreciate the appeal. Finally, I can see the big picture.

STRAVA ARTISTS ON INSTA

Check out the jaw-dropping creations of the world’s best Strava artists on their Instagram accounts…

Nicolas Georgiou @nico_georgiou

Anthony Hoyte @anthony.hoyte.90

Jean-Sébastien Weiss @Js_Weiss

This feature originally appeared in Cycling Weekly magazine on 13 November 2025. Subscribe now and never miss an issue.