Three Is Just a Number

– by Mario Crescibene

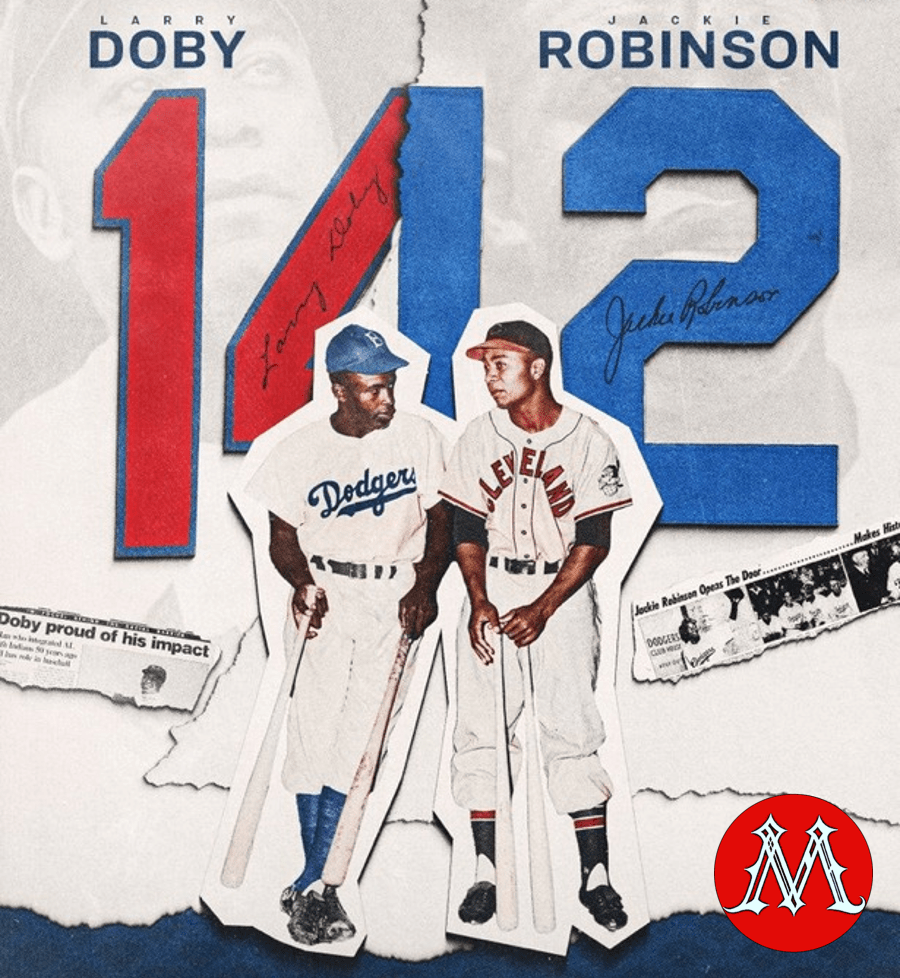

Major League Baseball honors three players with league-wide commemorative days. Larry Doby isn’t one of them. I wanted to know why — despite integrating the American League — MLB refuses to honor Larry Doby with his own day. So I reached out to the Cleveland Guardians and Major League Baseball to find out why.

Advertisement

The Guardians coordinated with MLB and provided an official response:

Major League Baseball has league-wide days for three individual players – Jackie Robinson, Roberto Clemente, and Lou Gehrig. While there are a lot of players who have made an enormous impact on the game both on and off the field, MLB has saved the significant distinction of a league-wide tribute to these three select players. They were selected because:

-

Jackie was the first player in all of baseball to break the color barrier

-

Gehrig for his courageous fight against ALS which is still a degenerative disease that MLB and its clubs raise money and awareness for

-

Clemente, who meant an enormous amount to the community of Latino players and fans. Clemente lost his life in tragic fashion as he was bringing supplies to earthquake victims and as a result, MLB honors him each year with a special day and an award recognizing the social responsibility efforts of its players.

The league response highlighted the ways in which they do honor Doby:

After his retirement, MLB hired Doby where he worked in several capacities… for 13 years (1990-2003), making significant contributions to the office… Major League Baseball has [also] honored Larry Doby by creating the Larry Doby Award which is presented to the MVP of the Futures Game.

The response also pointed out that he is already a highly celebrated legend here in Cleveland:

The Guardians have honored Larry Doby regularly including a statue at Progressive Field, retired number #14, and establishing “Doby Day” playing home annually to honor his debut day July 5, including promotional item giveaways to fans.

From the official response, one thing is abundantly clear: while Cleveland honors Larry Doby, the league he integrated does not. MLB says honoring three players league-wide is enough. Let’s explore Larry Doby’s impact on baseball, and see if he makes a case for a fourth.

Larry Doby integrated the American League in 1947, just eleven weeks after Jackie Robinson broke baseball’s color barrier. But those eleven weeks made all the difference in how they were prepared for what was coming.

Advertisement

Jackie Robinson had Branch Rickey — the Dodgers executive who spent years planning integration, who counseled Robinson on what to expect, and built an institutional support system around him. Robinson spent the 1946 season in the minor leagues, learning to handle the pressure and hostility before ever stepping onto a major league field. Larry Doby had none of that. No mentorship. No institutional plan. No preparation period. He was playing in the Negro Leagues one day and in the major leagues the next.

As Doby said:

“Jackie had it better in one way. When he went to spring training in 1946, he had a whole year to get adjusted. I came up in the middle of the season. I was 23 years old, and I had to perform immediately.”

“Nobody showed me the ropes. There was nobody to talk to, nobody to explain what to expect. I was completely alone.”

And when he met his new teammates, it wasn’t with open arms. While Jackie Robinson eventually found allies in the Dodgers clubhouse — teammates like Pee Wee Reese who famously put his arm around Robinson at Crosley Field, publicly showing solidarity — Larry Doby walked into a Cleveland clubhouse that wanted nothing to do with him:

“Some of the players turned their backs on me, wouldn’t shake my hand. It was a very lonely feeling. Even when you’re on the field, you’re alone.”

“There were some players who wouldn’t room with me, who wouldn’t sit next to me on the bus or in the dugout. I had to overcome that, and it was difficult.”

He received racist treatment as the Indians traveled across the country as well. While his white teammates checked into team hotels, ate at team restaurants, and traveled together, Doby was barred from joining them. Hotels refused him rooms. Restaurants turned him away. In city after city, he had to navigate unfamiliar streets searching for Black neighborhoods where he’d be allowed to sleep and eat. After night games, exhausted from playing, he’d have to find his own lodging — sometimes miles from the ballpark — while his teammates rested comfortably at the team hotel.

“I couldn’t eat with my teammates. I couldn’t stay in the same hotels. I’d have to go find a black family to stay with, or stay in a completely different hotel across town. And then the next day, I was expected to play like nothing was wrong.”

The racist treatment continued for years, but of course, despite every obstacle thrown in his way, Doby would go on to have a Hall of Fame career. In 1948, he hit .301 and helped lead Cleveland to the World Series, where he hit .318 and became the first Black player to hit a home run in a World Series game. His performance helped propel Cleveland to their last championship. From 1949 to 1955, he was named an All-Star seven consecutive times, leading the American League in home runs in 1952 and 1954, and in RBIs in 1954. Over his thirteen-year career, Doby compiled a .283 batting average with 253 home runs, 970 RBIs, and 1,533 hits before being inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1998. His impact extended beyond his playing days as he became the second Black manager in major league history when he took over the Chicago White Sox in 1978, was posthumously awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2023, and was honored by Cleveland with a retired number 14 and a statue at Progressive Field.

And despite always being “the second African American” to play baseball, Larry Doby never let it make him bitter:

“For a while, every time they mentioned me, it was ‘Larry Doby, the second black player.’ I never worried about being second. I just wanted to be treated as a ballplayer, as a human being.”

Larry Doby just wanted to be treated as a ballplayer, as a human being. Major League Baseball should start by treating him like the legend he is. His humility, Hall of Fame career, and groundbreaking legacy demand a league-wide day celebrating his contributions to baseball. Instead, MLB honors him with a minor league award — for a man who never played in the minors. The only thing more absurd than that is claiming there’s logic to their three-player policy. Why three? Is it for three strikes? Three outs? Well there are four balls to a walk, so give Larry Doby his base.

Advertisement

July 5th should be Larry Doby Day league-wide. Every team, every stadium, every player wearing number 14. Because the league he integrated owes him more than a Futures Game trophy.