Johnny Green shifted nervously in the queue for official media accreditation at the Grand Départ of the 2004 Tour de France in Liège, Belgium. While the journalists around him discussed the possibility of Lance Armstrong winning a record-breaking sixth Tour, the return of the peloton’s ‘bad boy’ Mario Cipollini, the prospects of debutants Fabian Cancellara and Thomas Voeckler or the time trial up Alpe d’Huez scheduled for stage 16, Green was distracted by other matters.

His ‘press card’ had been supplied by his friend, ‘Frank the Forger’, and there was still an outstanding arrest warrant for him in Belgium. Green wasn’t a member of the press pack. He was a middle-aged punk rocker and former road manager of The Clash who, nearly 30 years earlier, had crashed into a traffic bollard while driving the band from a gig just outside Liege.

He’d been “on the run” from the Belgian police ever since. When he finally received his access-all-areas laminated pass, it was the start of a three-week adventure that he would later turn into a book, Push Yourself Just a Little Bit More: Backstage at the Tour de France.

On publication in 2005, the book was hailed by the Sunday Times as “sports writing to blow your mind”. There were few, if any, English-language books about the Tour de France available at the time, let alone one written by a punk rocker in the style of Danny Dyer hot-desking with Ernest Hemingway.

This is his encounter with Eddy Merckx, for example: “I’d seen Eddie [sic] around Le Village time to time. Quite often shovelling fresh cream gateaux into his gob by the plateful. The first time I realised that the Cakeman was Eddie, I nipped over and shook his hand. Then I walked back to [my son] Earl and said to him, ‘Shake the hand that shook the hand’.”

Green died in March this year at the age of 75, on the 20th anniversary of the book’s publication. His son Earl was 23 and had just graduated from film school when his dad invited him to join him on his Tour de France escapade. (Also invited was Green’s close friend, referred to in the book only as ‘The Brief’, who took the photographs featured here.) “It was great seeing him in action,” Earl recalls his dad’s journalistic instinct. “His view of the world, the way he responded to stuff he saw, how things gave him a kick, was unique. He was always looking for an angle.”

(Image credit: Earl Green)

Green’s most controversial angle was on doping, which was prevalent in the professional peloton at the time. He draws parallels between riders and rock stars who produced remarkable work while taking drugs – from fivetime Tour winner Jacques Anquetil to Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards – before pointing out that no one ever refers to the latter as “drug cheats”. “I don’t necessarily agree with my dad’s views on doping,” says Earl. “But what he loved was the rich history of the sport, and part of that history is the doping – who was on what, when and how.”

The latest race content, interviews, features, reviews and expert buying guides, direct to your inbox!

In the book, Green is drawn to the sport’s “bad boys” such as Armstrong – “I don’t give a flyin’ f**k that the French nation is deeply suspicious of Lance,” he writes – and Italian sprinter Cipollini, who enraged organisers by leaving every Tour he entered after the first week’s flat stages to go on holiday to the beach.

Green is disappointed that Cipollini’s team hadn’t been invited to the Tour the previous three years, even when “Super Mario” had been world champion. He witnesses his hero having his trademark, cartoon-styled skinsuit being trimmed by “two roadies with nail scissors” to comply with UCI regulations before the prologue of the 2004 Tour.

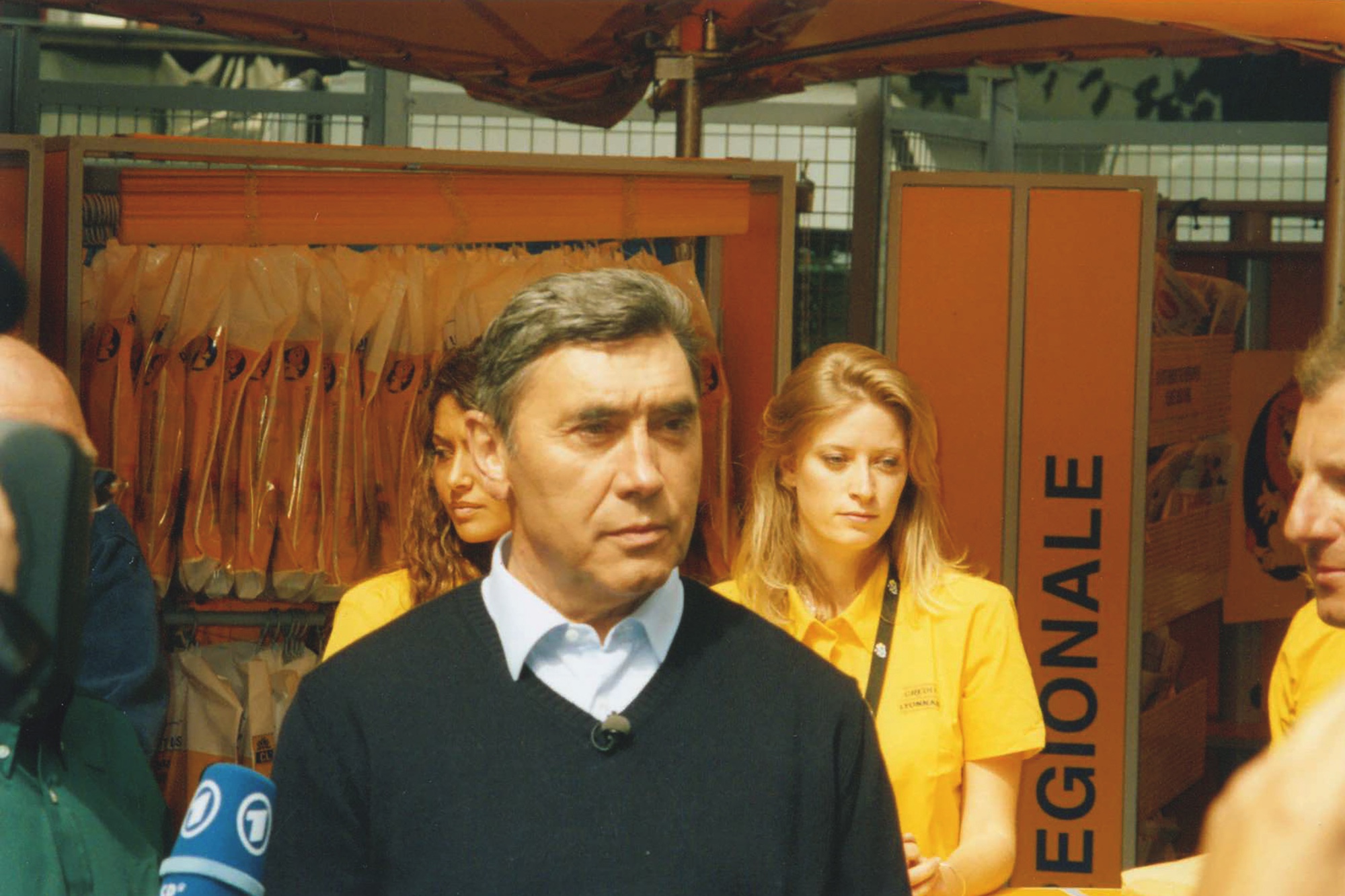

Johnny Green remembered Eddy Merckx for the amount of cake he ate

(Image credit: Earl Green)

“Mario’s discarded costume lay on the road, replaced by his golden flesh,” writes Green. “Camera flashes, jaws droppin’, a big hubbub. The Italian went up the start ramp in his new ‘distressed’ look to a big ovation. The effect of his presence was truly fantastic. Waves of energy rippled off him.”

“The effect of Mario Cipollini’s presence was truly fantastic. Waves of energy rippled off him.”

Johnny Green

Drawing on his own experiences with the Clash – when he did everything from driving the band to buying singer Mick Jones’ hair dye – Green clearly loved the showbiz element of the Tour, from its larger-thanlife characters to the logistical challenge of setting up and dismantling the race’s infrastructure day after day.

“It was the chaos of it all that captured him,” says Earl. “It’s so vibrant, and it’s there right in your face where you can get up so close to the riders, in the same way that when he was with the Clash the audience were right up against the music and he and the band would let the fans into their dressing room.” The sport’s raw edge appealed to Green. “It’s very similar to punk rock in that way, or at least it was when we were there. It was like the Wild West. We were told we were lucky to have caught the last days of it because so much of it has become corporate and for the VIPs since then.”

Green empathised with backstage characters such as “Belgian Bob” – the driver for race director Jean-Marie Leblanc – and Jean-Louis Pagès, the “Directeur des Sites”, who was responsible for the start and finish zones of each stage, referred to by Green as “the livin’, pumpin’ heart of Le Tour”.

“He’d stumbled into this crazy, chaotic national institution of a race by chance 20 years ago,” writes Green, describing how Pagès had been working as a school teacher when his brother-in-law asked him for help in organising the car parking for the race. “Before that, he’d never seen Le Tour. Shaboom! It transformed his life. It hit him like a punch in the face. Like rock’n’roll at its best. In a parallel universe, I’d bumped into the Clash on a Belfast stage in ’77 and never looked back.”

Johnny Green wrote an award winning book even if his press pass was faked

(Image credit: Earl Green)

Green had jumped at the chance of joining the Clash – initially as a roadie – rather than using his degree in Arabic and Islamic Studies to get “a proper job”. He stayed with them for three years – a period breathlessly recalled in his 1997 memoir, A Riot of Our Own: Night and Day with The Clash – and remained friends with them afterwards, joining the surviving members for their induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2003. He even persuaded singer Joe Strummer to accompany him to that year’s Tour. Sadly, Strummer died before the unlikely encounter between the punk rock hero and the professional peloton could happen.

Pirate material

It was watching Marco Pantani ascend the Col du Galibier on Channel Four TV’s coverage of the 1998 Tour that sparked Green’s love of pro cycling. By the end of the 2004 edition, son Earl was also hooked. “Whereas my dad was useless and only rode along the seafront from his home in Whitstable to Herne Bay [in Kent] on a Dutch sit-up-and-beg bike at a leisurely pace, I bought a proper bike and cycled to Copenhagen and back on it,” he says. “I used it to commute from home in Margate to Canterbury until my accident.”

Earl was cycling home from work in 2012 when he crashed into a piece of lorry debris on the road. It tore into his spinal cord, leaving him confined to a wheelchair. “But my life’s not that bad,” he says, echoing his dad’s carefree, punk ethos. “I can walk a bit with a Zimmer frame and use an exercise bike. And I got compensation, so I don’t have to work anymore!”

Green ensured he looked into all aspects of the Tour, not just the riders

(Image credit: Earl Green)

Having been brought up by his dad alone for several years following his mum’s death when he was just 18 months old, Earl, who is now 43, has always been proud of his dad’s achievements – from his time with the Clash to his later work as educational advisor on sex and drugs for Kent County Council – but their adventure at the Tour de France has a special place in his heart. “The Tour is so much bigger than the riders and results, it’s a living breathing thing that takes in the stories, characters and history of France,” says Earl.

“My dad managed to pull together all those different strands, all the unsung heroes of the Tour, both from its history and from what was happening in front of us there and then.”

The finished work was shortlisted for the William Hill Sports Book of the Year, ironically losing out to a book about football written by Gary Imlach, the presenter of ITV’s Tour coverage. “It was the trip of a lifetime,” says Earl. “The fact I have it in the form of a book is a lovely memory of my dad and a souvenir of a great adventure.”

Cycling’s rock and rollers

Other figures from the rock and roll industry with a passion for road cycling include:

Kraftwerk: When on tour in the early 1980s, co-founders Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider would regularly be dropped off 100 miles from the venue and cycle the rest of the way. The band released a single, Tour de France, in 1983, and 20 years later an album, Tour de France Soundtracks, to coincide with the Tour’s centenary edition.

Echo and The Bunnymen: Guitarist Will Sergeant and bassist Les Pattinson were confirmed roadies. They organised a bike ride for fans on the day of their 1984 ‘Crystal Day’ gig in Liverpool.

John Cooper Clarke: The Salford punk poet knew he wanted to become a cyclist after his Uncle Dennis moved in with his family: “He was a member of a cycling club, owned a beautiful bike with drop handlebars and was the most successful man with women I’ve ever known.”

Lloyd Cole: A relatively new convert to road cycling, the singer-songwriter posts his rides on Strava, accompanied by lengthy essays on everything from the weather to how his knees felt.

Talking Heads: Frontman David Byrne takes a folding bicycle on his travels around the world. He wrote about his adventures in his 2009 book, Bicycle Diaries.