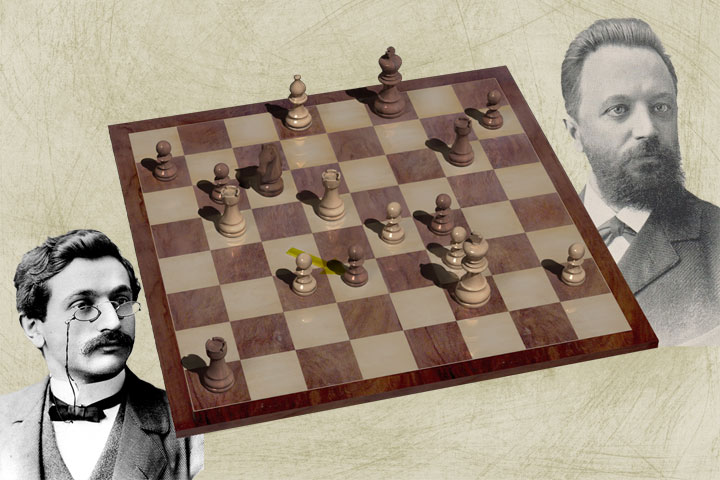

In May 1894, Emanuel Lasker somewhat surprisingly defeated the 58-year-old Austro-American William Steinitz in a 19-game match played in various cities across North America, by a clear score of 10:5. Thus, the title of World Champion passed to the then 25-year-old German. But experts were quick to express doubts about his qualifications, considering him a relatively inexperienced newcomer.

Lasker was willing to accept Steinitz’s challenge for a rematch, but only at a later date. In the meantime, a tournament was to determine the true hierarchy in the world of chess. Five years after the Congress in Manchester, another major chess event was to take place in England in the summer of 1895, for which the organisers in the popular seaside resort of Hastings were able to raise an attractive prize fund.

From 5th August to 3rd September, 22 players from all over the world should meet in a single round-robin tournament. As was customary back then, the time limit was two hours for 30 moves, followed by one hour per 15 moves. Games were played regularly on five days of the week, with the sixth day reserved for any unfinished games. Each day consisted of up to eight hours of play, split into two sessions: one from 1 pm to 5 pm in the afternoon and one from 7 pm onwards. So the players had a month of hard work ahead of them.

Among the big favourites were Steinitz and Lasker, with the latter seemingly having recovered well from the typhoid fever he had suffered in autumn 1894. But so were Dr Siegbert Tarrasch from Nuremberg, who had won several strong tournaments in a row, and Mikhail Chigorin from St. Petersburg, who had lost to Steinitz twice in world championship matches, most recently in 1892 by a narrow margin. Representatives of the younger generation, such as David Janowski from Paris, Harry N. Pillsbury from Boston and Carl Schlechter from Vienna, were considered to have only an outside chance at best.

In the first round, Lasker defeated Vienna’s Georg Marco in a rather erroneous game. Meanwhile, Chigorin gained the upper hand over Pillsbury by taking a wild course that even included the early sacrifice of a rook.

The following day saw the first ever meeting between two major protagonists of that era. The New York Sun, 7th August 1895, reported: “Chigorin had a much harder fight against Lasker. This contest was hotly, though evenly, conducted in the opening and middle game, neither side being able to make the least progress toward establishing a winning position. Toward the end Lasker was altogether outplayed, and he had to resign after fifty-six moves.” Over the past 130 years, this game has been commented on and analysed many times. This includes contemporary chess magazines, books on middlegame strategy and more recent game collections.

Sources and abbreviations used (in chronological order):

Hof = La Stratégie (15. August 1895), p. 239, notes by L. Hoffer

DWZ = Deutsches Wochenschach (18. August 1895), p. 279

DSZ = Deutsche Schachzeitung (August 1895), p. 237

BCM = British Chess Magazine (September 1895), p. 397, notes by W. Wayte

Stei = Horace F. Cheshire: “The Hastings Chess Tournament” (London 1896), p. 30, notes by W. Steinitz

Sch = Emil Schalopp: “Das internationale Schachturnier zu Hastings” (Leipzig 1896), p. 71

Kob = Alexander Koblenz: “Lehrbuch der Schachstrategie 1” (Berlin 1980), p. 224

Sergei Soloviov: “Emanuel Lasker 1, Games 1889-1903” (Sofia 1998), p. 181

Garry Kasparov: “My Great Predecessors, Part 1” (London 2003), p. 102

KM = Linder, I. & Linder, V.: “Emanuel Lasker” (Milford 2010), p. 71, notes by K. Müller

GK = Garry Kasparov: “Moi velikie predshestvenniki, Tom 1” (2nd ed., Moskva 2020), p. 118

In the presentation of the game, I have already included a few selected excerpts from the various comments. These are intended to provide guidance on the different strategic themes, but also to point out some of the numerous controversial moments.

Click on the notation to get a replay board with engine.

There are regular disputes about the correct notation of historical games. In this case, it is about the exact moment when Lasker resigned. Of the six contemporary sources, two (Hof and DSZ) state that it was after 55…Rag1; three (DWS, BCM and Stei) after 56…Ke8; and one (Sch) after 57.Bg5 R6xg5. We stick to the majority and the daily press (New York Sun), according to which the game ended after 56 moves.

Contemporary commentators were therefore of the opinion that Lasker had gained an advantage from the opening, but that a balanced position had emerged after 19…f5 at the latest. As the game progressed, Chigorin handled his pair of knights (significantly) more skilfully than Lasker did his pair of bishops. Some expressed their appreciation, like “the whole game is played with great strategic finesse” (Hoffer) or “a masterly game, worthy of two great players” (BCM). Others treated Lasker very critically, such as Steinitz and Levenfish.

For a long time, Steinitz was the only one who at least questioned some of Chigorin’s decisions. Koblenz, for example, summarised: “However, if the position is blocked, the pair of bishops proves to be a fiction. The bishops do not always represent an advantage. This game illustrates what has been said.” From the 1990s onwards, the overall assessment began to change. According to Soloviov, followed by Kasparov in 2003, Lasker owned (significant) advantages during most of the game.

GK’s concluding commentary from 2020 is quite nuanced and summarises all the findings to date: “In this ultra-tense, far from faultless duel, it is not so much variants that are important as the text of the game itself: Chigorin was after all playing with the world champion, and, as always, he upheld his principles! In the given instance, this was a struggle of two knights against two bishops in a semi-closed position and the blockade of a pawn centre. And on the whole, although Lasker twice in the course of the game gained the better chances, he did not demonstrate a superiority in a very complex game rich in tactics.”

Much to the misfortune of human chess players, recent decades have shown that, thanks to increasingly powerful chess engines, the detection of small tactical details can nullify even the most profound strategic considerations. Therefore, it is not surprising that, in 2020, GK changed many of his lines and evaluations from 2003, overturning some of them entirely. However, he refrains from making clear assessments in some places, and at least one very important moment has not yet been identified at all.

So, it is time to get down to work and take a closer look at some of the game’s turning points. In an analysis, it is often very helpful to tackle the simple questions first and then work your way up to the more complex problems. In chess, this usually means starting the analysis of a game from the end.

Question 1

Almost all commentators consider White to be hopelessly lost here. Lasker played 55.Rxd3 and had to resign two moves later.

Instead 55.Bc7 Ra2+ 56.Kf1 Rgg2 57.Rxd3 Rxh2 58.Kg1 is given by Steinitz as well as Kasparov as the best defence. While the 1st world champion says “and it is not so clear that Black can win”, the 13th states “the struggle is prolonged for a long time”.

Can you confirm GK’s assessment that Black is winning?

Question 2

At the time, the consensus was that “White’s game cannot be saved”, as reflected in Hoffer’s comment on Lasker’s 48.Rb5.

As evidence, for example DSZ cites: “48.Rxc4 fails due to 48…Nxd4+ etc., and even after 48.Bc2 exd4 49.Bxd4 Nxb4 50.cxb4 Rh5, White is lost.” Both alternatives are also discussed briefly by GK: “Perhaps more persistent is 48.Rxc4!? Nd6 49.Rxc6 Rxc6 50.dxe5 Rxe5 51.Ba2 or 48.Bc2!? exd4 49.Rxc4 Nd6 50.Rxc6 Rxc6 51.cxd4, relying on the strength of the bishops.” Of course, we want to be more precise.

Can White avoid losing with 48.Rxc4 and/or 48.Bc2?

Question 3

This is the position in the game that was talked about the most, with everyone condemning Lasker’s 47.Rd2.

Among the classical commentators, some recommended 47.Ba2 (such as Steinitz), others 47.d5 (such as Chigorin), but most favour 47.Bc2. Later, Levenfish added 47.dxe5 to the mix. Kasparov considered all of these suggestions and concluded: Best is 47.Bc2! Nc6 48.Rbb1, which “still left White the better chances.”

Can you work out if GK’s approach will result in a winning position?

Question 4

So far, Chigorin’s knight retreat 37…Nf6 has gone almost uncommented. Instead, a viable option to consider is 37…Nc7 38.Bxf4 e5. GK offers a minimal insertion: “37…Ne3!?“. Before him, Karsten recommended: The pair of bishops “should be halved by 37…Ne3 38.Bxe3 fxe3 39.Kxe3 Ra5 with better drawing chances than in the game.”

Can any of the two ideas bring salvation for Black?

Question 5

This is truly uncharted territory. No one has dared to say anything about Chigorin’s 36…gxf4 yet. There were some critics of the move before, 35…g5, from Steinitz to Kasparov, as this “ultimately opens the position for White’s bishops”, as Karsten puts it. However, in the given situation, engines are quick to flash out either 36…h6 or 36…g4 as improvements.

What are your thoughts on these suggestions? Do you think any of them will really make a difference?

Further considerations

It almost seems as if there are opportunities for improvement, or at least respectable alternatives, in many of the moves in the game. Like, instead of 50.Bh4, there are two candidates available: 50.Bd4 and 50.Rdd5. Or, instead of Lasker’s 42.Raa1, the central pawn push 42.e5 did not escape the eye of the commentators, from Chigorin to Kasparov. Was Steinitz right in saying that 33…g5 is better than Chigorin’s realisation of the same plan with 35…g5?

Of course, there are also plenty of questions about the early stages of the game. Was Lasker really already winning after the queen exchange on move 13, as Levenfish and Kasparov suggest? Did Chigorin play flawlessly from 18…c4 to 32…Nf7, as all commentators, including Kasparov, claim?

Whether it is the impression of a particular moment or analytical ‘proof’ that this or that move wins or not. Please feel free to explore what interests you most and share your insights with us!