Just to recap: Manchester United recorded the fourth-highest revenues of any soccer club in the world, per Deloitte’s most recent accounting. They pay the fourth-highest wages of any soccer club in the world, per the estimates from FBref. And they finished 15th … in their own domestic league.

Of course, these things happen sometimes. Jürgen Klopp’s Borussia Dortmund finished seventh in 2014-15. That same season, José Mourinho’s Chelsea won the Premier League, but the year after that? Mourinho was fired during the season, and the team finished 10th.

For Man United, this was not a one-off season where the ball kept bouncing the wrong way or whoever was kicking the ball on the other team temporarily turned into Lionel Messi. Based on a blend of 70% expected goals and 30% actual goals — our best estimator of true team strength — Manchester United were … the 15th-best team in the Premier League.

It was not a one-off poor season, either. United’s past four Premier League finishes: sixth, third, eighth and 15th. Their past four seasonlong goal differentials: zero, plus-15, minus-1 and minus-10. There’s one outlier there — and it’s not last season.

So, United are a legitimately bad team that (a), has been getting worse and (b), has tons of money.

They’re not close to winning anything, and they’re also able to outbid just about anyone in the world to acquire the best young players in the world. And compared to other clubs in their financial stratosphere, they can offer big salaries and lots of playing time to whoever they acquire. Without the stresses of potentially winning the Premier League or competing in the Champions League, they could focus on building the foundation of the next great Manchester United team.

Now, they could be doing that, but they absolutely are not. With new billionaire Jim Ratcliffe running the show and a new coach in Ruben Amorim roaming the sidelines, this summer is proving that nothing has really changed. Manchester United are still a complete mess.

Do Man United want to win the Premier League or not?

A couple weeks ago, I wrote the following:

“Two years ago, I looked at the makeup of the starting lineups in each of the previous five Champions League finals. What I found is that those players joined their clubs at an average age of 23.8. More than half of the players signed with their teams before their 24th birthday and more than 80% joined before their 27th birthday. In this year’s ESPN FC 100, players were acquired by their current clubs at an average age of 22.7, while more than 40% joined before their 21st birthdays.”

The point is: World-class players typically join their clubs well before the peak soccer-playing years of 24 to 28.

Now, it can happen, but it’s rare that someone who’s available at, say, 25, 26 or 27 ends up being a difference-maker on a Premier League or Champions League title contender. Stars tend to break out at younger ages, so they get scooped up early by the kinds of teams that pay competitive wages and don’t let their best players leave.

It’s probably not a coincidence that the best teams aren’t signing many players in this age range, either. Peak-age players cost more because they’ve already become established names. But when you’re signing a peak-age player, it means you’re signing him after he’s played at least one of his peak-age seasons for a club other than yours. And, when players in the 25-to-27 age bracket don’t pan out, they don’t generate much interest from other teams because they tend to be on big wages and are older.

I went over all of this because I was looking at the moves Arsenal were making. After years of only signing young players, they’ve moved for a much experienced profile in this transfer window. Even for a team that’s coming off three straight second-place Premier League finishes and a Champions League semifinals appearance, these moves are risky.

But what about for a team that’s conceded 11 more goals than its scored over the past two years? Manchester United have signed two players this summer, and they’ll both be 26 at the start of this upcoming season. It doesn’t really matter what you think about Bryan Mbeumo and Matheus Cunha as players. Maybe they’re actually two of the best players in the Premier League. And maybe they’ll both get a boost from playing with what is (theoretically) a more talented group of teammates than the teams they’re leaving.

Even if that’s true, their best seasons for Manchester United are likely to be their next two. Is that the time frame into which last season’s 15th-place finisher should be investing nearly €150 million?

Why Mbeumo and Cunha won’t score as many goals for United

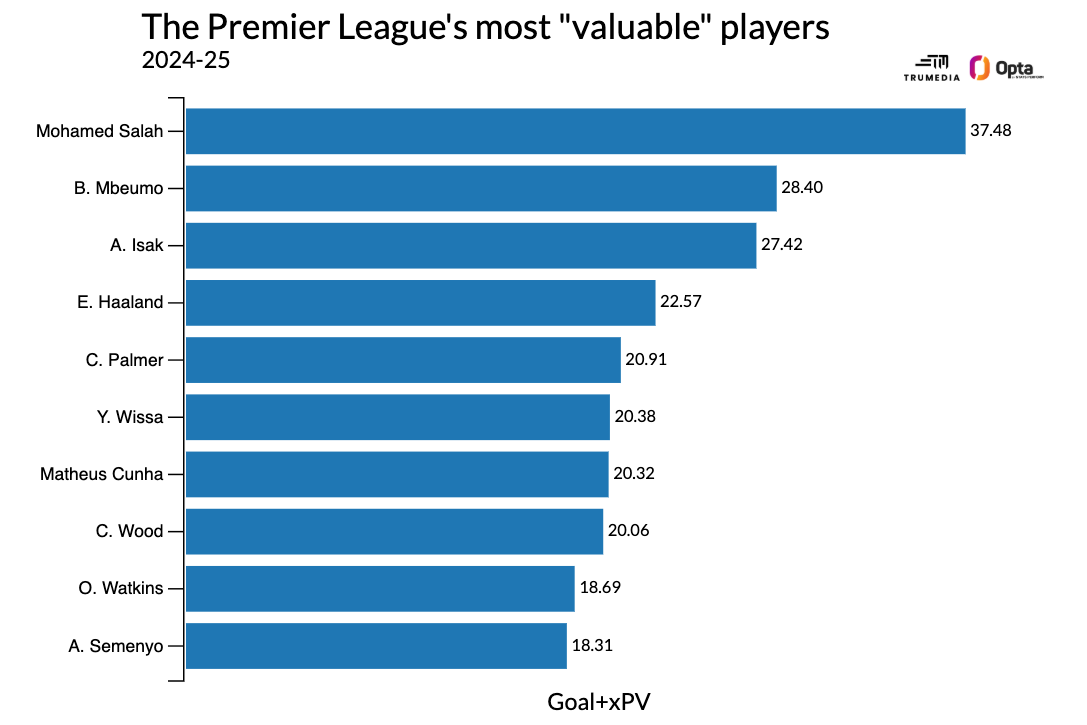

One simple way to determine how much value a player provided to his team is to look at goals and expected possession value added. The first, you know: how many times a player put the ball across the end line, between the posts and under the crossbar. The second is Stats Perform’s model that puts a value on every non-shot thing a player does on the ball: how much each tackle or pass or etc. increases his team’s chances of scoring.

By this method, Cunha and Mbeumo were two of the most valuable players in the league last season:

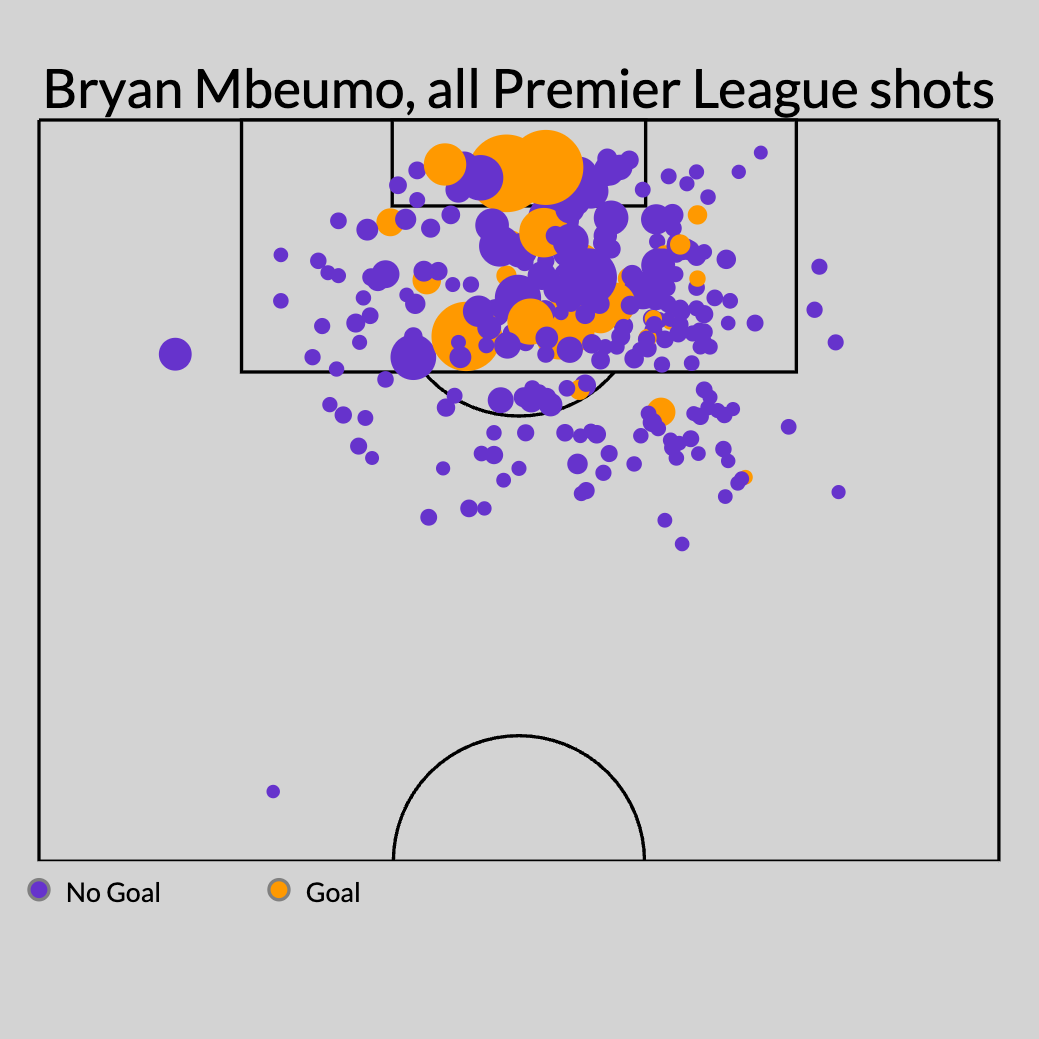

There is no doubt Cunha and Mbeumo helped their respective teams win lots of points last season, but that’s not the same thing as saying that they’re going to do it again next season for their new teams. For starters, Mbeumo took free kicks and penalties for Brentford last season — neither of which seems likely at United, where club captain Bruno Fernandes handles both duties.

And, as I wrote about last week, Mbeumo and Cunha were the league leaders in overperforming their expected goals. While fans disappointed by players such as Darwin Núñez and Nicolas Jackson will view this as a good thing, it’s most likely random noise.

Although Cunha scored 6.4 goals more than expected this past season, he was actually 2.7 goals below expectation in his previous six seasons in Europe. Same goes for Mbeumo. He was 7.5 goals above expectation this past season, but he was 3.4 goals below expectation in the previous five campaigns. You can convince yourself that both of these players suddenly become elite finishers — but you absolutely should not bet on it.

At a glance, it looks like Manchester United signed the fourth- and eighth-highest scorers in the Premier League. And well, that is a fact — they did do that. Mbeumo scored 20 goals and Cunha had 15. But if they both just finished the exact same set of chances at the same rates they had over the previous five seasons, Mbeumo would’ve ended up with around 12 goals, Cunha somewhere between eight or nine. Take out the penalties and Mbeumo would’ve been somewhere between eight and nine. United, though, are paying as if the blazing-hot finishing is going to continue.

These players do more than just score goals, but when you’re signing players who suddenly have career-outlier seasons in front of goal, you really need to do a cold-blooded analysis of how likely any of that is to continue. This is how you run a soccer club if you’re serious about winning. And guess where the betting markets are putting their over/unders for the upcoming season? Cunha is at 10 goals and Mbeumo is at eight.

What is Manchester United’s long-term plan?

There is an argument that you can’t just build an entire team out of young players. There is an argument that Manchester United were so bad last year that they need to invest in some sure-thing players who will erase the possibility of, gulp, relegation. Also: vibes. A couple above-average Premier League veterans and even a minor uptick in results will be good for the culture that Luke Shaw recently referred to as “toxic.”

That would be believable if anything else happening at United suggested any kind of coherent plan, but it doesn’t.

1:23

Nicol: I wouldn’t go to Man United if I was Sesko

Steve Nicol expresses his concerns over a potential move to Manchester United for Benjamin Sesko.

Based on past on-field performance, Alejandro Garnacho is the most exciting young prospect at the club. He has 24 goals and assists in the Premier League before his age-21 season, and he’s averaging about 0.5 non-penalty expected goals and assists per 90 minutes in his career — or right around where James Maddison, Gabriel Martinelli and Phil Foden were last season. Players who do that at such a young age tend to have quite successful careers.

If we only look at last year, recently-turned 23-year-old Amad Diallo‘s performance was the lone bright spot in a dark season. He scored eight goals and added six assists before injuring his ankle in February.

Both players at least have the potential to become contributors to a Champions League team, and they will save the club millions of dollars in transfer fees if they do. But they play the same positions as Mbeumo and Cunha. So, the choice is to either not play two of the most expensive players on your squad or to block playing time for your most promising young players. Or, in Garnacho’s case, completely remove one of your most promising young players from the squad.

Garnacho, along with Jadon Sancho, Antony and Tyrell Malacia were all left home from United’s preseason tour of the United States. This was supposed to facilitate all of their moves away from the club, but by signifying to the rest of the soccer world that these players are totally unwanted, you’re cutting your legs from under you. Why would any club be willing to negotiate higher transfer fees for players they know that you don’t want? Unsurprisingly, no one has.

Some reporting from my colleague Rob Dawson also suggests that United are confused about how negotiations work. United were upset that Brentford continued to ask for more money for Mbeumo, but then they also … paid Brentford what they were asking for? You don’t have to sign a player if the asking price gets too high! There are hundreds of thousands of other professional soccer players out there.

Per Dawson’s more recent reporting, United are now looking at two options to fill the center forward spot between Cunha and Mbeumo: RB Leipzig‘s Benjamin Sesko and Aston Villa‘s Ollie Watkins.

Sesko is an inexperienced 22-year-old physical standout, while Watkins is a solid 29-year-old Premier League producer. How are these your two targets? Putting aside that they’re not similar players at all, signing Watkins would be trying to optimize the next season or two, while signing Sesko would be trying to optimize 2027 through 2030.

Back in March, Ratcliffe himself said that the club were targeting 2028 for their next realistic shot at a Premier League title. That would be two seasons after the upcoming campaign. However, he admitted “that’s probably slightly on the short end of the spectrum. But it’s not impossible.” Let’s give him a tiny bit of grace here and say that he really meant 2029. By then, Mbeumo will be 29, Cunha will be 30 and Watkins will be 33.

While United are saying that they want to win in the future, everything they’re doing is telling us that they can’t wait. No, they want to win now.