The great Akiba Rubinstein (1 December 1880 to 15 March 1961)

Akiba, or Akiwa Rubinstein, born on 1 December 1880 and died on 15 March 1961, was one of the greatest players in chess history and perhaps the strongest of his time who did not become world champion. His active career stretched from 1903 to 1931, not quite thirty years. Much of Rubinstein’s life, both before and especially after his brilliant chess career, remains largely in the dark.

There was long disagreement about Rubinstein’s exact date of birth. Chess historians have now settled on 1 December, the date that also appears on his gravestone. Rubinstein was born into a Jewish family in the small town of Gmina Stawiski in what is now north-western Poland. At the time of his birth, the region belonged to the Russian Empire. His father died a few days before he was born. Rubinstein had thirteen older siblings, all but one of whom died of tuberculosis in childhood. His mother remarried, and Rubinstein gained a younger half-brother. The family then moved to Bialystok.

Rubinstein learned to play chess at the age of fourteen. He played in the cafés of his neighbourhood and eventually managed to defeat the best local player, G. G. Bartoszkiewicz. At sixteen he decided to become a professional chess player.

In 1903 Rubinstein, then in his early twenties, moved to Lodz, the centre of Polish chess. There he met Georg (Hersz) Salwe (1862–1920), the leading Polish player of the time. Through many training games Salwe became Rubinstein’s teacher and trainer.

From 1903 onward Rubinstein competed in tournaments. His first event was the All-Russian Championship in Kiev, where he already finished fifth. In 1905 he played in the Hauptturnier in Barmen and shared first place with Oldrich Duras. In 1906 he won a four-player tournament in Lodz, finishing ahead of Mikhail Chigorin, and came second behind his mentor Salwe in the All-Russian Championship in St Petersburg. With his victories in the international tournaments in Ostend in 1907 (together with Ossip Bernstein) and in Karlsbad, Rubinstein had established himself among the world’s leading players.

Akiba Rubinstein at around 25 years of age

Karlsbad 1907, seated: Rubinstein, Marco, Fähndrich, Tschigorin, Schlechter, Hofter, Tietz, Maróczy, Janowski, Dr. Neustadtl, Drobny, Marshall. Standing: Nimzowitsch, Wolf, Mieses, Cohn, Johner, Leonhardt, Salwe, Vidmar, Berger, Spielmann, Dus-Chotimirski, Tartakower, Dr. Olland

At the All-Russian Championship in Lodz in 1907, Rubinstein played his game against Georg Rotlevi, which entered chess history as his “Immortal”.

Rubinstein played not only tournaments in the years that followed but also a number of matches, all of which he won. With the exception of an early match against Salwe at the beginning of his career, Rubinstein won every match he played.

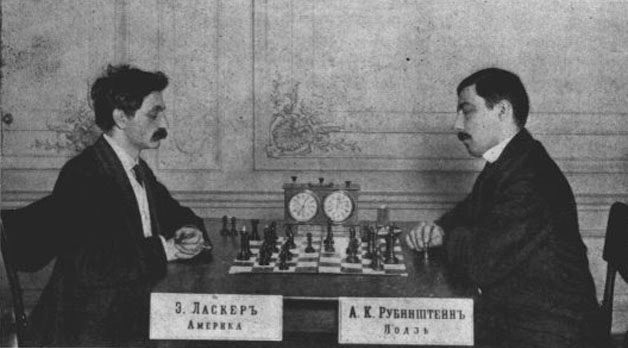

He was invited to tournaments in Vienna and Prague and achieved good results there. In 1909 he won the supertournament in St Petersburg together with World Champion Emanuel Lasker, finishing three and a half points ahead of the rest of the strong field.

Lasker and Rubinstein

The name Emanuel Lasker will always be linked with his incredible 27 years reign on the throne of world chess. In 1894, at the age of 25, he had already won the world title from Wilhelm Steinitz and his record number of years on the throne did not end till 1921 when Lasker had to accept the superiority of Jose Raul Capablanca. But not only had the only German world champion so far seen off all challengers for many years, he had also won the greatest tournaments of his age, sometimes with an enormous lead. The fascinating question is, how did he manage that?

In 1910 Rubinstein moved to Warsaw. At the Warsaw City Championship he had to settle for second place behind Alexander Flamberg. He won a match shortly afterwards by a clear margin. For health reasons Rubinstein had to withdraw from the championship in Hamburg as well as from a planned match against Ossip Bernstein.

In the following year he took part in the tournament in San Sebastián and finished second behind the young rising star José Raúl Capablanca, with Rubinstein handing the Cuban one of his few defeats.

He was a child prodigy and he is surrounded by legends. In his best times he was considered to be unbeatable and by many he was reckoned to be the greatest chess talent of all time: Jose Raul Capablanca, born 1888 in Havana.

In 1912 Rubinstein continued his run of success with a series of excellent tournament victories in San Sebastián, Bad Pistyan, at the 18th DSB Congress, and at the All-Russian Championship in Vilnius.

EXPAND YOUR CHESS HORIZONS

Data, plans, practice – the new Opening Report In ChessBase there are always attempts to show the typical plans of an opening variation. In the age of engines, chess is much more concrete than previously thought. But amateurs in particular love openings with clear plans, see the London System. In ChessBase ’26, three functions deal with the display of plans. The new opening report examines which piece moves or pawn advances are significant for each important variation. In the reference search you can now see on the board where the pieces usually go. If you start the new Monte Carlo analysis, the board also shows the most common figure paths.

In 1913 Rubinstein was, according to Jeff Sonas’s retrospective calculations, the best player in the world. As early as 1912 Rubinstein had sent Emanuel Lasker a challenge for a world championship match. Lasker accepted in principle but had already given Capablanca a commitment. Negotiations dragged on, and eventually a date was agreed for the autumn of 1914, with venues in Russia and Germany. Rubinstein spent several months in Bad Reichenhall in 1913, perhaps already preparing for the match.

At the St Petersburg tournament in 1914, however, Rubinstein was eliminated in the preliminary stage. Soon afterwards the First World War brought international tournaments and organised chess to a halt for years. During the war Rubinstein still played two tournaments in Poland.

Even before the First World War, contemporaries had reported the first oddities in Rubinstein’s behaviour. His depression and his fragile nervous system were beginning to show. The political and economic upheavals at the end of the war wiped out his financial savings, and he lived under precarious conditions thereafter, which may have contributed to his unstable state of mind.

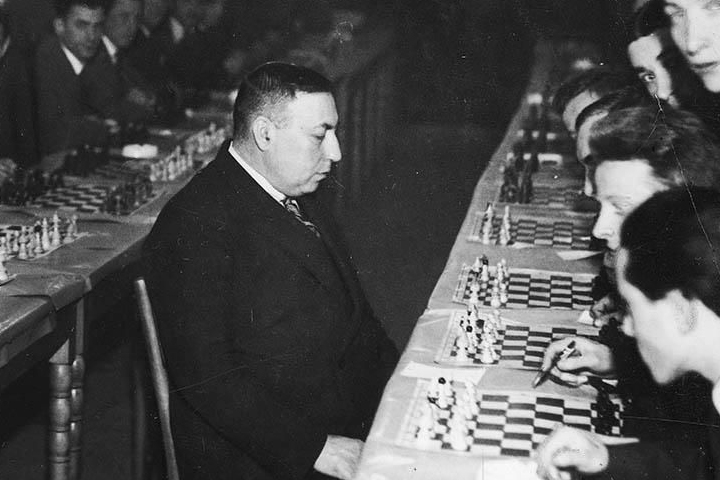

He married in 1917. A year later his son Jonas was born. In 1919 the family moved to Gothenburg in Sweden. Rubinstein played tournaments and matches in Sweden, Berlin and Warsaw, and gave simultaneous exhibitions.

At the beginning of 1920 Rubinstein defeated Bogoljubov in a match and, during a simultaneous tour in the Netherlands, reminded the chess world that he still had an agreement with Lasker for a world championship match. Lasker was also negotiating with Capablanca, and unlike Rubinstein, Capablanca had financial backers who could meet Lasker’s demands. In 1921 Lasker lost the title to Capablanca. The Cuban accepted a challenge from Rubinstein, but Rubinstein was never able to meet Capablanca’s financial requirements, and the match was never held.

In 1921 Rubinstein played the international tournament in The Hague, finishing a respectable third behind Alexander Alekhine and Savielly Tartakower. He won a four-player double-round tournament in Triberg ahead of Efim Bogoljubov and Richard Reti.

In 1922 he achieved good results and upper-table finishes in tournaments in London, Hastings and Prague, and he won the Masters event of the Vienna Chess Congress ahead of Tartakower, Tarrasch and Alekhine. Rubinstein defeated Alekhine in only 26 moves, having lost twice to the future world champion earlier that year in London and Hastings. During 1922 Rubinstein and his family moved from Gothenburg to the vicinity of Potsdam. At the turn of the year 1922–23 Rubinstein also won the Christmas Congress in Hastings, while his twelfth place in Karlsbad in May 1923 and his tenth place in Mährisch Ostrau in July of the same year were unusually poor results by his standards.

In 1924 and 1925 Rubinstein again achieved mostly good results in his tournaments, including second place at Baden-Baden 1925 behind Alekhine. In November 1925 the first major international chess tournament in the Soviet Union was held. Bogoljubov won ahead of Lasker. Rubinstein finished only fourteenth among the twenty-one participants.

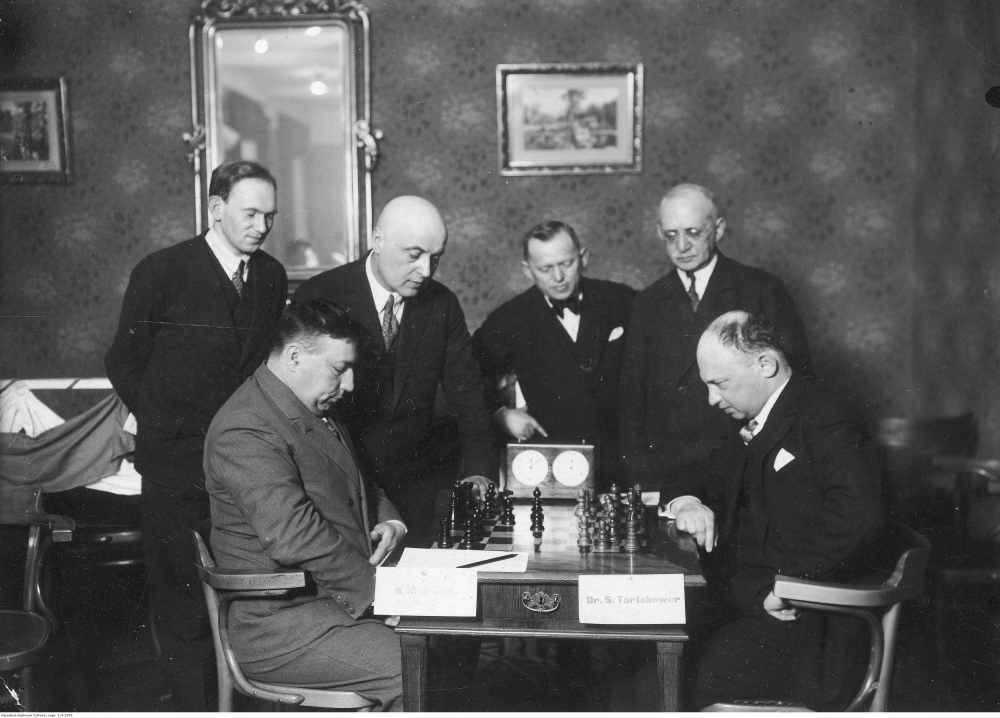

Bogoljubov and Rubinstein, 1925

In March 1926 the world’s leading players were invited to the Panhans Hotel at Semmering. Rubinstein finished in a respectable sixth place. Rubinstein’s poor financial situation moved Hans Kmoch to publish a book of the master’s best games, Rubinstein’s Winning! with the proceeds intended for Rubinstein. During 1926 Rubinstein and his family moved from Germany to Antwerp in Belgium. In 1927 their second son, Samy, was born. In Belgium Rubinstein initially remained in contact with the country’s players and for a time seems to have had a few students, among them Alberic O’Kelly and Paul Devos (1911–1981).

Between 1926 and 1930 Rubinstein still played a considerable number of tournaments, including top events, and continued to achieve good results. In 1927 he won the national championship of Poland, and in 1930 he played for the Polish team at the Chess Olympiad in Hamburg, winning team gold and scoring 15 out of 17 on first board, the best individual result of the event.

At the 1927 Polish Championship, playing against Tartakower

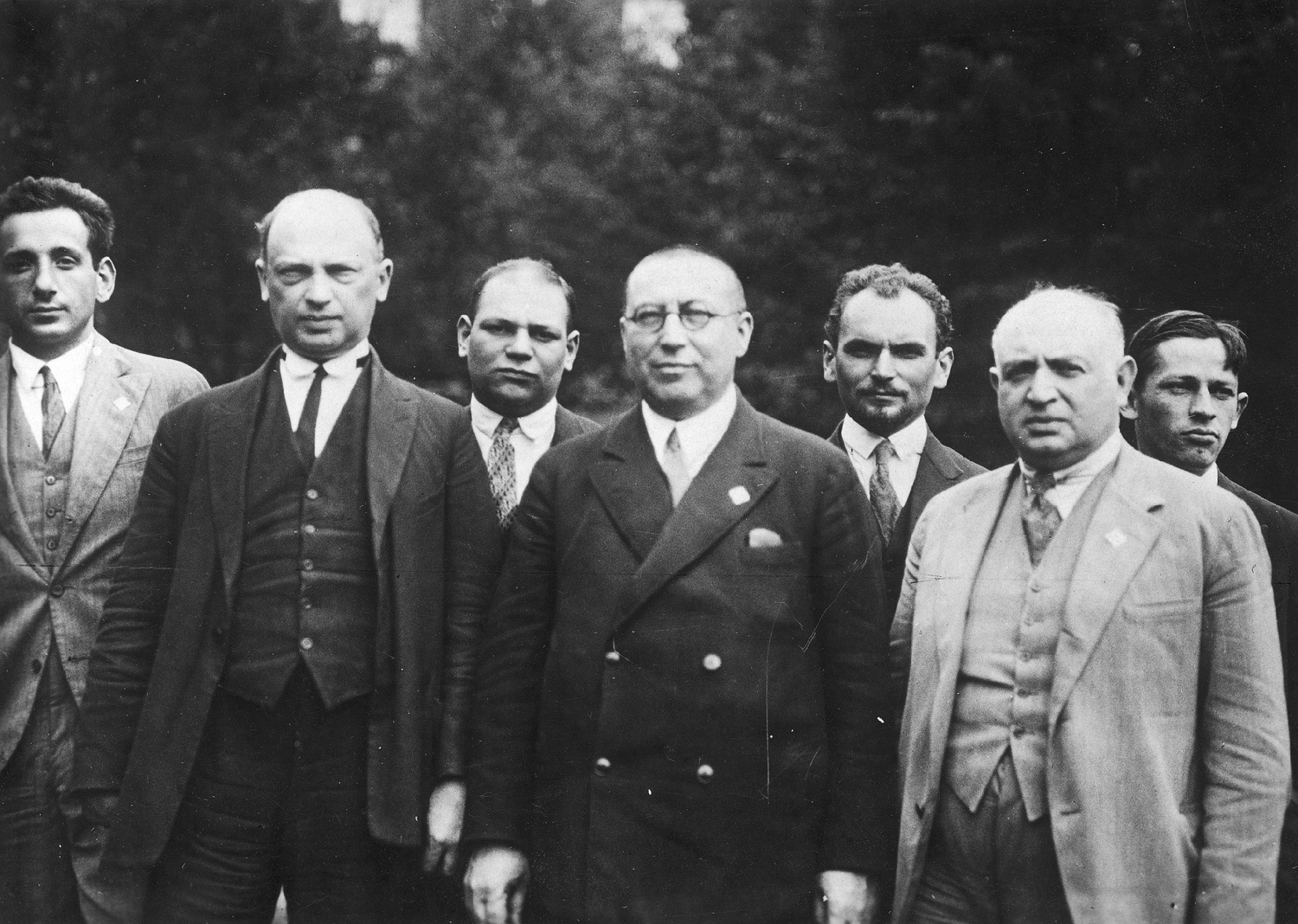

The Polish team 1930

Rubinstein, however, was already becoming disoriented away from the board. According to reports by his teammate Tartakower, the team’s attendant often had to bring Rubinstein back to his seat, as he would lose his way in the rooms of the Mozart Halls in Hamburg’s Masonic Lodge and was unable to find his way back alone.

In the spring of 1931 Rubinstein became the first top professional to undertake a simultaneous tour in Palestine. At the Chess Olympiad in Prague in the summer of 1931 he again played for Poland, but his result was no longer as strong (+3, −2, =7). In December he finished last in a small four-player tournament in Rotterdam. It was his final tournament. A few simultaneous games from 1931 have been preserved.

Because of his condition Rubinstein had to withdraw from competitive chess in 1931. The family now lived in an apartment in Brussels above an inn run by Rubinstein’s wife Eugenie. Rubinstein no longer took part in social life. At times he is said to have stayed in a sanatorium.

Rubinstein occasionally received visitors. Around 1936 Hans Kmoch visited him and was shocked by Rubinstein’s state, as he had by then become largely neglected. After the German occupation of Belgium, SS officers are said to have searched for the Jewish Rubinstein family, but according to an anecdote they decided not to take Rubinstein with them after seeing him. His son Samy (1927–2002), however, was later arrested and imprisoned in a camp near Mechelen in 1943–44.

In the 1940s the Canadian master Daniel Yanofsky visited Rubinstein. A game from his 1946 visit has survived. O’Kelly visited occasionally. A visit by Miguel Najdorf in the early 1950s is also recorded. Rubinstein’s last public appearance as a chess professional took place in 1946 at a simultaneous exhibition in Liège.

In 1950 Rubinstein was among the players who were awarded the grandmaster title honoris causa by FIDE.

After his wife Eugenie died in 1954, Rubinstein became even more withdrawn. His sons placed him in the Jewish retirement home at Rue de la Glacière 31–35, where on some days he would not leave the room he shared with another resident. He still had an interest in chess, though. He replayed games on his pocket set or analysed positions with his sons when they visited him.

When the retirement home in Rue de la Glacière was temporarily closed for renovation, the residents were moved to Antwerp. Akiba Rubinstein died there on 15 March 1961.