Greg LeMond’s 1986 Tour de France victory wasn’t historic just for his being the first American, non-European winner – it was a breakout moment for cycling sunglasses too. LeMond wore Oakley’s Pilot Sunshades, catapulting the brand into the spotlight and onto the faces of pros and amateur cyclists alike. Road cycling fashion was changed forever.

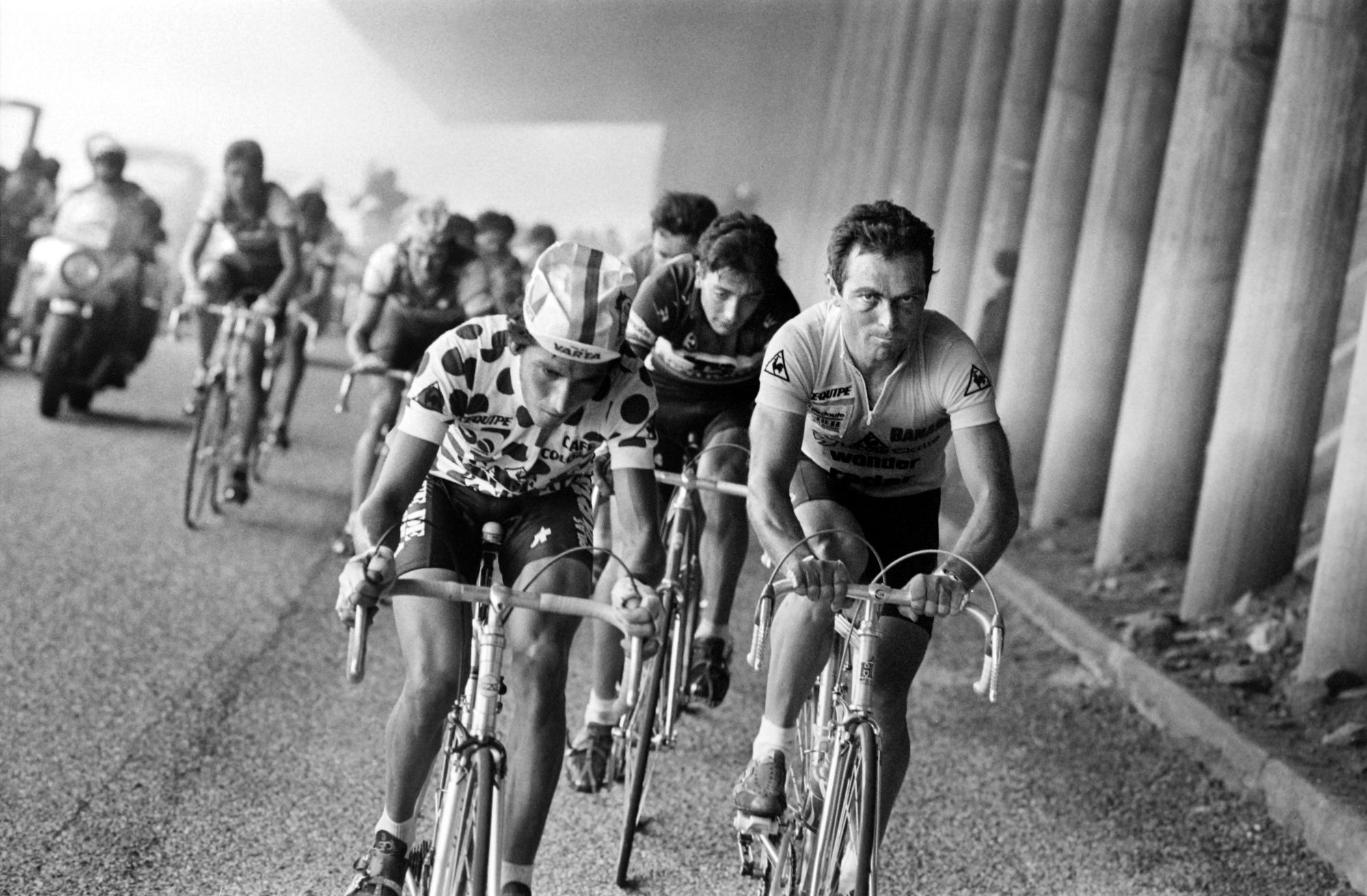

Early road racers had worn modified flying goggles, but with the rise of paved roads with less dust and grit, some riders began wearing aviator-style sunglasses, which, popularised by Italian cycling legend Fausto Coppi, became the style of choice in the 1950s.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

There was no way Hinault was going to jump on the Oakley bandwagon ; instead, he selected an emerging Italian brand called Rudy Project. While Hinault was a marketing coup for Rudy Project, he wasn’t the brand’s first sponsored athlete. Ahead of its time in recruiting sporting influencers, the Italian firm had already signed Italian road racer Moreno Argentin on the eve of the 1986 UCI World Championships in Colorado Springs-which he won, resplendent in a pair of Super Performance shades. “Super Performance were the first sunglasses for Rudy Project,” says the company’s marketing manager Irene Lucarelli.

A technological leap forward, the Rudy Project Super Performance model was made by Grilamid and had polycarbonate lenses. “These materials were much safer compared to glass. Protection, together with performance, was indeed the very first goal for us,” added Lucarelli. For the first time, a pair of cycling sunglasses could protect from UV rays without posing a risk of eye or facial injury in a crash.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

After the mid-1980s sunglasses surge, innovation slowed. Tweaks were made, such as the addition of air vents and interchangeable lenses, but the basic wraparound design was largely unchanged. In 1989, however, Oakley struck gold with the launch of the M Frame, first worn by Belgian Classics specialist Johan Museeuw and later made iconic by Lance Armstrong-by the mid-1990s, every amateur rider was coveting, if not wearing, a pair of Oakleys.

Rudy Project kept the brand rivalry alive by responding with a new design, the Ekynox, and paying Armstrong’s biggest rival Jan Ullrich to wear them. New competitors were emerging on the sunglasses scene too. Briko, known for snow sports, entered cycling with sponsorships of Italian stars Marco Pantani and Mario Cipollini. Their bug-eyed Raider 2 and Stinger models challenged the wraparound norm. Briko’s Thrama lenses promised improved clarity and enhanced UV protection, prompting both Oakley and Rudy Project to rethink their designs.

Johan Museeuw was one of the first to wear Oakley sunglasses, but then wore Briko’s while riding for the all conquering Mapei team.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

The race for the most radical innovation spawned such monstrosities as Miguel Induráin’s 1996 Rudy Project Sweeto TT helmet with ‘windows’, and David Millar’s outrageous Oakley Over The Top shades at the 2000 Sydney Olympics.

Despite internal struggles, Oakley remained dominant into the 2000s , helped by further top-tier athlete endorsements: Armstrong, of course, but also rising sprinting star Mark Cavendish. The market was growing ever more crowded, and by 2007 Oakley faced retail challenges and was forced to merge with eyewear giant Luxottica. The deal reignited creativity, and in 2008 Oakley launched the Jawbone series of Racing Jacket models, known for their easily swappable lenses and made prominent by Cavendish, whose rockstar image elevated the glasses to cult status.

“As cycling’s popularity surged in the 2010s, more brands seized their moment”

When Team Sky formed in 2010, Oakley came on board as a co-sponsor, equipping the Wiggins-era squad with custom-coloured Jawbones and Radars. The partnership continued for a decade, even after the team became Ineos Grenadiers – with Geraint Thomas helping keep Oakley on top with his signature white Racing Jackets.

As cycling’s popularity surged in the 2010s, yet more brands seized their moment. With online shopping and social media making it easier for newcomers to make their mark, brands including 100% – which, like Oakley, had motocross roots – began vying for pro endorsements.

In a new era of rivalries, 100% signed Peter Sagan, creating a head-to-head with Oakley-wearing Cavendish, the former’s 100% Speedcrafts becoming instantly recognisable in the peloton. POC made a splash in 2013 with its boxy ‘Hesjedal Edition’ Do Blade, worn by Giro d’Italia winner Ryder Hesjedal. Despite the onslaught of competition, Oakley remained dominant until 2022.

(Image credit: Getty Images)

The big change three years ago came when Ineos Grenadiers ended its long-standing partnership with Oakley, sparking speculation about what Geraint Thomas would wear next. His white Racing Jackets had become his trademark, making him instantly identifiable. With just three weeks to go before the 2023 Giro d’Italia, Sungod had a serious challenge on its hands. The answer came in the form of the Sungod GTs , a model designed to meet Thomas’s preferences – a model that has since become a best-seller for Sungod.

Today, sunglasses remain a defining part of any rider’s look. Whether boxy or wraparound, eyewear is about more than performance; just as in 1985, it’s about following the pro aesthetic. Scicon, once reeling from the loss of Mark Cavendish to Oakley, has surged back with a headline signing of its own, Tadej Pogačar. Its Aeroshade model- a modern riff on the classic Jawbone design – has helped the brand rise to prominence. Oakley remains a heavyweight, of course, with Jonas Vingegaard among its star athletes, but its dominance is no longer guaranteed.

In cycling, eyewear has always told a bigger story than mere sun protection, one of technology, fashion, ego and rivalry. And with new brands rising as fast as new champions, the battle for the sport’s most coveted sunglasses is far from over.

PAYING THROUGH THE NOSE?

Top-of-the-range cycling sunglasses from the premium brands cost upwards of £200 a pair – but what’s the real difference from a £20 pair of Foster Grants? CW tech ed Andy Carr writes : Oakley developed its own ‘plutonite’ lenses – essentially a high-grade polycarbonate – which it claims offers improved clarity and impact resistance.

Decathlon’s Van Rysel sunglasses, used in World Tour racing and priced around £60, use polyamide: a nylon that’s lighter and thinner than polycarbonate, while remaining shatter-resistant. So why the big price difference? Manufacturing and finishing. Cheaper glasses often use flat-cut lenses, whereas pricier options may use curved or spherical lenses for a wider, less distorted field of view – which are harder to produce.

Premium shades are also more likely to feature anti-scratch coatings, hydrophobic layers, and better optical quality. Ultimately, it’s not just the material – it’s what brands do with it. And you’re paying for the name, of course.