In 2023, the Dodgers finally retired the number 34, worn with distinction by Fernando Valenzuela. It had been 42 years since the season of Fernandomania, 26 years since Valenzuela last threw a pitch in the major leagues.

Better late than never. The Dodgers generally do not retire the numbers of players not selected for the Hall of Fame, but it is never too late to do the right thing.

Advertisement

On Sunday, a committee is set to vote on whether Valenzuela should be admitted to the Hall of Fame. To the committee members: We commend Valenzuela to you with that same adage — it is never too late to do the right thing.

“He deserves to be in the Hall of Fame,” said longtime Dodgers broadcaster Jaime Jarrín, himself a Hall of Famer.

“The Hall of Fame is a special, special place, of course. But, what Fernando did for baseball, very few have done.”

Eight players are on the ballot, given a second chance at Cooperstown after the Baseball Writers Assn. of America passed on them all: Valenzuela, Barry Bonds, Roger Clemens, Carlos Delgado, Jeff Kent, Don Mattingly, Dale Murphy and Gary Sheffield.

Advertisement

The 16-person committee includes seven Hall of Famers, two owners (the Angels’ Arte Moreno is one), four former general managers, two writers and one statistician. Each committee member can vote for up to three players; 12 votes are required for election.

By the numbers alone, Valenzuela’s candidacy is borderline. Sandy Koufax or Clayton Kershaw, he was not.

Still, of the 90 pitchers in the Hall, according to Baseball Reference, Valenzuela had a better earned-run average (3.54) than 11 of them. One of them, Jack Morris, had a 3.90 ERA. He was elected by a committee just like the one that will consider Valenzuela.

Morris was a workhorse and five-time All-Star best known for one game: a 10-inning shutout in Game 7 of the 1991 World Series. But Valenzuela, a workhorse, Cy Young Award winner and six-time All-Star, threw a 147-pitch complete game in Game 3 of the 1981 World Series, with the Dodgers at risk of losing the first three games of the series. The career postseason ERA for Valenzuela: 1.98. For Morris: 3.80.

Advertisement

Read more: Dodgers Dugout: Jaime Jarrín discusses Vin Scully, Fernando Valenzuela and Muhammad Ali

If you’re evaluating Valenzuela on the numbers alone, you’re missing half the story, and the legacy of a player that transformed a city and a sport.

The Dodgers built their stadium on land that was previously home to three Latino neighborhoods. The city of Los Angeles had envisioned grand housing projects there and kicked out the residents, long before the Dodgers moved from Brooklyn. The projects never were built, but many Latinos considered the destruction of the neighborhoods and removal of the residents as something of the Dodgers’ original sin and vowed never to set foot inside Dodger Stadium.

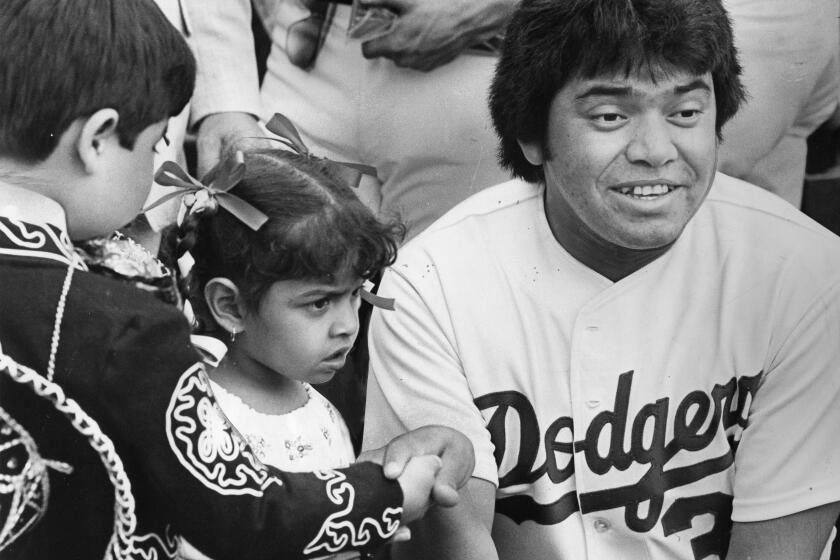

Until 1981, that is, when a shy, modestly pudgy and virtually anonymous Mexican 20-year-old showed up, looked to the heavens before every pitch, and started his rookie season with eight consecutive victories, including seven complete games and five shutouts.

Advertisement

That was the origin of Fernandomania.

Shohei Ohtani lures baseball fans from everywhere. Valenzuela lured humans from everywhere.

“People who hadn’t really thought about baseball, or Dodger Stadium,” said Peter O’Malley, who became the Dodgers’ president in 1970 and then owner from 1979-1998. “Suddenly, they were coming. They were flying from all over to see him.

Fernando Valenzuela looks up before throwing a pitch. (Jayne Kamin-Oncea / Los Angeles Times)

“He captured the imagination of everyone. It was the most exciting time for me on my watch.”

If they didn’t come to Dodger Stadium, they came to see him somewhere else. President Reagan invited Valenzuela to a White House event with the president of Mexico.

Advertisement

“He was able to create such interest in baseball — not only in the Dodgers, but baseball in general,” Jarrín said. “In St. Louis. In Atlanta. In New York. In Chicago. They went wild when Fernando was throwing — 10,000 extra people at the ballpark when he was pitching.”

The Dodgers hurriedly set up a radio network in Mexico, so Jarrín’s broadcasts of Valenzuela’s games could be heard south of the border.

And talk about bringing the city together: In Los Angeles, half the television sets in use were tuned to a Valenzuela start on one Friday night, 60% on one Sunday, The Times reported.

“It was like watching the pope,” actor Danny Trejo said in the Times’ 12-part Fernandomania @ 40 documentary series. It’s worth watching, especially if you are one of the committee members voting Sunday.

Advertisement

The series did not focus on interviews with players, or with fans. Valenzuela’s impact on the community was told largely through the words of a playwright, a filmmaker, a historian, an actor, a singer, a songwriter, and a mayor.

Said O’Malley: “He has never gotten the credit he deserves for the impact he made on baseball — not just on the Dodger organization, but on Mexican baseball, international baseball, and the community.”

Read more: Dodgers star Fernando Valenzuela, who changed MLB by sparking Fernandomania, dies at 63

Valenzuela belongs in the Hall of Fame because his legacy outlasted his career.

Advertisement

The Dodgers did not draw 3 million fans in any of their first 20 years in Los Angeles. They drew 3.6 million in Valenzuela’s first full season, 3.5 million in his second, and now 3 million is a disappointment rather than an aspiration.

Jarrín said the Dodgers’ Latino fan base had grown from “8, 9, 10%” when he started calling their games in 1959 to close to 50% now.

And, when Valenzuela debuted, O’Malley said international baseball was “a nonexistent subject” in league meetings. In the wake of a World Series that set record ratings in Canada and Japan, and in anticipation of the World Baseball Classic three months away, Valenzuela’s election to the Hall of Fame would be not only worthy but entirely fitting.

Fernando Valenzuela in 1982. (George Rose / Los Angeles Times)

The Hall of Fame includes players born in Canada, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, Japan, Panama, Puerto Rico, the Netherlands and Venezuela.

Advertisement

Valenzuela would be the first player from Mexico. The Hall of Fame’s motto: “Preserving history, honoring excellence, connecting generations.” Who better fits?

“A whole nation is very aware of the Hall of Fame,” Jarrín said. “I’m sure they would declare a holy day on the day Fernando gets in.”

And we know what we would say: If you have a sombrero, throw it to the sky.

Sign up for more Dodgers news with Dodgers Dugout. Delivered at the start of each series.

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.