So far this summer, Premier League teams have spent transfer fees of at least €35 million on 21 different players. And of those, 12 are joining from clubs outside of the Premier League.

The two most expensive signings of the summer — Florian Wirtz and Hugo Ekitike, both to Liverpool — are coming from the Bundesliga. Arsenal‘s two biggest signings, Martín Zubimendi and Viktor Gyökeres, were players from the top-flight leagues in Spain and Portugal, respectively. And two of Manchester City‘s three major moves, Tijjani Reijnders and Rayan Cherki, brought in new contributors from Italy’s Serie A and France’s Ligue 1.

If you’ve been following the Premier League for long enough, perhaps you read all of that and just started doing the thing reflexively: mocking an enraged local fan calling into TalkSPORT radio or impersonating the least-prepared talking head on Sky Sports. But, you can’t help yourself from thinking, can he do it in the Premier League?

Back in 2010, pundit Andy Gray infamously suggested that Lionel Messi “would struggle on a cold night at the Britannia Stadium,” home of Stoke City.

This was 18 months after Messi scored a header in a 2-0 win over Manchester United in the Champions League final. And it was during a season that would conclude with Messi scoring the go-ahead goal in a 3-1 Champions League final win against Manchester United — a match that would lead Sir Alex Ferguson to call Messi’s Barcelona “the best team I’ve faced.” Oh, and Stoke City? They lost 2-1 to Man United at home and finished the season with a minus-2 goal differential.

So, the idea of English soccer’s inherent superiority extends back to a time when its first division was clearly not superior — and that timeframe extends way, way, way before Gray’s comments, too. But sometimes reality and delusion can cross paths.

Given the economic might of the Premier League 15 years later, it seems reasonable to assume that the by-far-richest soccer league in the world might also be the hardest league to play in. But if that is true, then can we move beyond the stereotypes about cold weather, long throw-ins and cheering about tackles and corner kicks? And can we pinpoint why, exactly, it might be so much harder to play in England than the world’s other top-flight leagues?

How the Premier League became the best league in the world

Seemingly every year, we look at the results in the Champions League and have a debate about what is the best league in the world. This year, though, that debate died. Paris Saint-Germain won the Champions League, and no one outside of maybe France president Emmanuel Macron would be willing to argue with a straight face that Ligue 1 is the best soccer league in the world.

In reality, the debate should have died years ago. The best teams in the Premier League might not always be better than the best teams in France or Spain, but thanks to a massive financial advantage, it’s all-but-impossible for any other league to be as good from top to bottom.

Based on the estimated wage data from FBref for this past season, all 20 Premier League clubs ranked in the top 50 for the highest wage bills across Europe’s Big Five leagues. If wages were distributed evenly across leagues, then each league would only have about 10 teams in the top 50. And it’s the same story with the crowd-sourced transfer valuations from Transfermarkt. Among the 25 most valuable rosters in the world, 12 come from the Premier League. Evenly distribute those, and everyone should have five in the top 25.

For the Premier League to not be the most competitive league within that environment, there would have to be a massive scouting and tactical discrepancy, with English clubs blindly guessing while everyone else knew what they were doing, but only in a way that no one in England ever picked up on. And you would need a global workforce of players and coaches to not really care about getting paid as much as they can. With England’s now-diverse ownership groups, coaching staffs and playing populations, none of that is true.

This is clear in any attempt anyone makes at quantifying the strength of a given league. Analyst Tyson Ni recently released a publicly available set of team ratings that uses betting-market odds to estimate team strength. The ratings are represented as the expected goal differential for a given team were they to play the worst team in the dataset. And per Ni’s ratings, the averages for the Big Five leagues are as follows:

• Premier League: 2.51

• LaLiga: 2.24

• Serie A: 2.06

• Ligue 1: 2.01

• Bundesliga: 1.96

Put another way, the average Premier League team would be expected to beat the average LaLiga team by 0.27 goals, the average Serie A team by 0.45 goals, the average Ligue 1 team by 0.50 goals and the average Bundesliga team by 0.55 goals.

The Club Elo ratings, meanwhile, mirror closely the wage and transfer-value data. The Elo system awards or subtracts points after every game a team plays, based on the final score, location and quality of the opponent. It’s purely results-based; there are no estimates. And currently, all 20 Premier League clubs rank in the European top 50, which includes teams beyond just the Big Five leagues. No other league even has 10 clubs in the top 50.

What makes the Premier League so hard?

The simple answer is that the players are better, and so the teams are better.

While in LaLiga you would have a bunch of tough games against the two traditional powers and the likes of Atletico Madrid, Villarreal and Athletic Club, the Premier League presents you with 38 games against top-50 teams in the world. The goalkeepers are better at saving shots, the defenders are better at defending, the midfielders are better at breaking up attacks and keeping the ball, and the attackers are harder to stop.

Using one of the catchall player valuation models — VAEP (Valuing Actions by Estimating Probabilities), which essentially judges everything a player does on the ball based on how much it increases his team’s chances of scoring or decreases his team’s chances of conceding — analyst Tony ElHabr looked at how player performance changed when players changed leagues. Simply: Did their VAEP go up or go down?

He studied the seasons from 2012 through 2020. And he found that when players moved to the Premier League from any of the Big Five leagues, their output decreased. LaLiga players suffered a 5% decrease, while Ligue 1 players dropped off by 10% and guys coming over from Serie A fell off by 12%. The biggest drop-off across the Big Five, though, came when players transferred in from the Bundesliga: a 17% drop-off, larger than players from Portugal and Brazil, and roughly equivalent to what happened when players made the step up from the Championship.

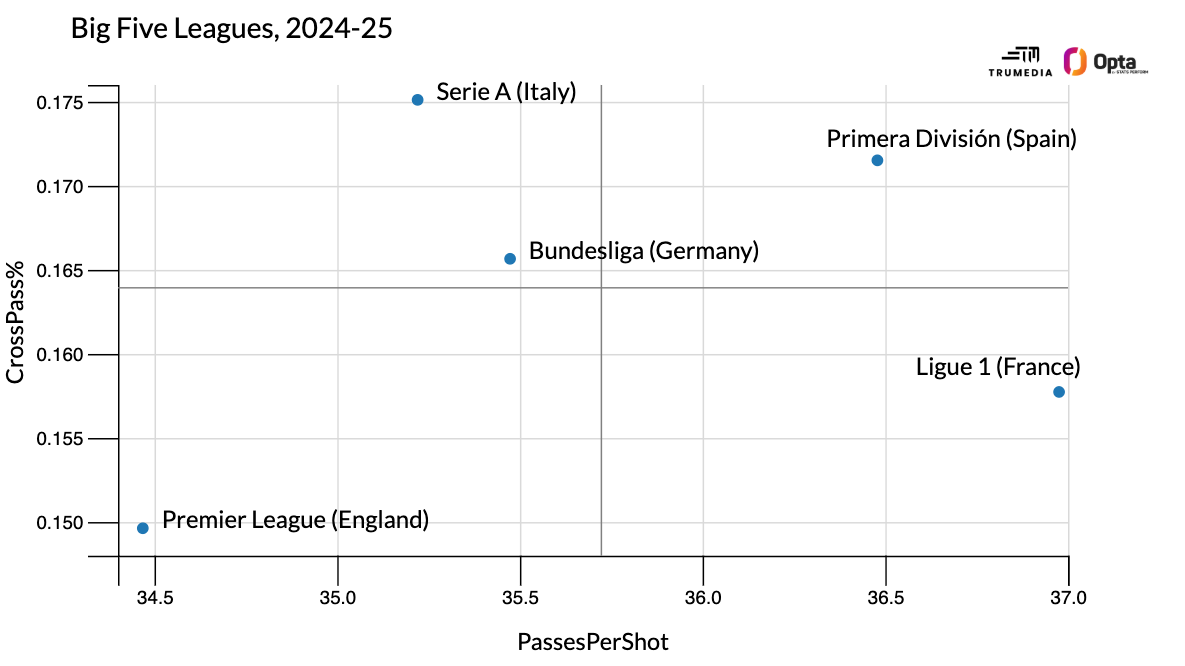

But how does this show up on the field? For last season, at least, the Premier League stood out in a couple ways. Compared to the other Big Five leagues, Premier League teams were more urgent in possession (measured by passes per shot) and they crossed the ball way less often (measured by the percentage of final-third passes that were crosses):

Except, Premier League teams also took the fewest percentage of shots from outside the box and they played the second-shortest passes on average. This wasn’t a league where the teams were bombing the ball up the field and shooting from distance. No, it’s a league where the average team are able to push possession forward with more intricate passing and then quickly move the ball into the box for shots without having to rely on crosses.

That demands a high level of technical skill from in-possession players, but it also demands a lot from out-of-possession players, too.

Despite those more efficient possession numbers, Premier League teams didn’t score more goals or create better chances than everyone else. To defend in the Premier League, then, you have to fend off the stress created by the shorter, more-aggressive passing approach in buildup play and then you have to deal with teams who aren’t crossing or shooting from distance but rather working the ball into the penalty area, where defensive errors get turned into near-automatic goals.

Smarter decision-making and shorter passing would not have been two phrases anyone would’ve connected with the Premier League back in 2010-11. The league has changed drastically as some of the best coaches from outside the country have helped transform the tactics.

At the same time, the Premier League hasn’t lost the one thing it has always had: running.

Per data from Gradient Sports, Premier League sides reach high-end speeds more often than any of the other leagues. Looking at all outfield players who featured in at least 600 minutes this past season, the average Premier League player reached a maximum speed of 32.5 kilometers per hour — nearly a quarter of a kilometer per hour faster than any other league.

Gradient then defines a sprint as any time a player reaches 25 km/h or more. The Premier League leads in the number of sprints, the distance sprinted, the time spent sprinting and the percentage of movement that was spent sprinting:

Those differences might not seem like much, but when multiplied by 10 players, across 20 teams, each playing 38 games per season? The Premier League is sprinting circles around the rest of Europe.

So, what does all that extra money get the Premier League? And why does it make it so hard for anyone coming from another league to succeed?

On the attacking end, you have to be able to keep possession, pass through the opposition and create chances inside the most crowded area of the field without relying on a low-probability shot from outside the box or an inefficient cross from the sideline. Without the ball, you have to try to break up these possession sequences where you don’t get bailed out by bad decisions and constantly need to make plays inside of your penalty area.

And then, even if you can handle that, it’s still not enough. For all the technical skill, patience and efficiency the league requires, you still have to be able to run — faster and more often — than everybody else.